As a multidisciplinary applied field, community psychology is remarkably situated to bring respect for the inherent dignity of all people. The soul-searing events of the summer of 2020, the Capitol insurrection of January 2021, increasing violence against Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, Islamaphobia, ongoing murders of Black people and the (dis)abled, and attacks on the Jewish community demonstrate that in the United States, wellbeing is far from uniform. Many organizations, neighborhoods, systems, policies, and places have not consistently enabled wellbeing. Manifestation of the power of human dignity, the value of civil society, civic discourse, the salience of collective efficacy, and community wellbeing are at the heart of community psychology. Collective efficacy is "a group's shared belief in its conjoint capabilities to organize and execute the courses of action required to produce given levels of attainments." This moment in time prompts a reexamination of paradigms, theories, and definitions alongside aligned practices and values that transcend the field.

Download the PDF version to access the complete article, including figures and tables.

As a multidisciplinary applied field, community psychology is remarkably situated to bring respect for the inherent dignity of all people (Bond, 2016). The soul-searing events of the summer of 2020, the Capitol insurrection of January 2021, increasing violence against Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, Islamaphobia, ongoing murders of Black people and the (dis)abled, and attacks on the Jewish community demonstrate that in the United States, wellbeing is far from uniform. Many organizations, neighborhoods, systems, policies, and places have not consistently enabled wellbeing. Manifestation of the power of human dignity, the value of civil society, civic discourse, the salience of collective efficacy, and community wellbeing are at the heart of community psychology. Collective efficacy is "a group's shared belief in its conjoint capabilities to organize and execute the courses of action required to produce given levels of attainments" (Bandura, 1997, p. 477). This moment in time prompts a reexamination of paradigms, theories, and definitions alongside aligned practices and values that transcend the field.

Traditional community psychology and allied traditional wellbeing research focus on manifestations of health, happiness, and thriving at the community level. The dynamic interplay of context, identity, and social policy has pronounced repercussions for wellbeing and disparities at the individual, family, neighborhood, and state levels (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Marmot, 2016; Wilkinson & Pickett, 2019; Williams & Cooper, 2019). Our multiple social identities and the cultural externalities of our lives are inextricably linked and ground self-perception, behavior, relationships, and the evaluation of others (Steele, 2011; Tajfel, 2020). How the self—endowed with multiple identities—persists and flourishes in daily life amidst numerous contexts is at the heart of wellbeing. In an affirming cultural context, we may thrive; in an aversive culture, we may be threatened and wither (Shinn & Toohey, 2003; Steele, 2011). Structural and systemic factors, implicit and explicit bias, environmental racism, and the resultant toll on traditionally marginalized populations in the United States make wellbeing as conventionally defined, nearly unattainable. A social justice framework aligns with emerging models from several disciplines to unveil the challenge of pluralism and the pernicious effects of racism in the United States. Inclusive policy, reflecting numerous perspectives, though elusive, is at the heart of enlightening practice and the creation of inclusive systems (Williams & Cooper, 2019; McGhee, 2021).

Definitions matter: Shared meanings are foundational to a field that aspires to engage colleagues and community. Definitions conceptualize meaning. The ways in which we conceptualize, describe and define the work of community psychology practice grounds a shared understanding of purpose, process, manifestations, and desired impacts. Generative definitions add exponential value to influencers, our culture, history, and prevailing narratives. Definitions are central to policy and system development, comprehensive interventions, and theoretical models (Rappaport, 2000; Trickett, 2009). Definitions are at the heart of a trajectory with potent, powerful, sociopolitical implications (Mollica, 2014; Prilleltensky, 2019; Wilkinson & Pickett, 2019). How community psychology welcomes community stakeholders, those most affected, and other disciplines are precipitated on its perceived identity. The braiding of strands of connection, the fabric of understanding, and resulting actions are tied to the shared definitions of community psychology practice or how the field defines itself. This moment in time calls for reflection on the meaning of community psychology practice and its image.

This article presents a case for revisions to a definition of community psychology practice that affirms dignity, human rights, physical and psychological health, and co-creation with community. Moreover, the field of community psychology examines the practice definition and alignment with disciplines, such as public health, gender, ethnic, racial, refugee and immigrant studies, feminism, and intersectionality in supporting and centering collective understandings and strategies to address systemic racism and marginalization.

Crenshaw (2017) articulated intersectionality as a framework in which multiple identities are simultaneously acknowledged; this concept is central to community psychology. In this paper, I use the phrase "traditionally marginalized populations" to include all communities of color, LGBTQ+, those living with a (dis)ability, immigrants, and refugees, those who are undocumented, Muslims and other religious minorities, people who have been incarcerated, people who have been in the foster care system, and people who are English learners. Community psychology designed for equity embraces intersectionality. The synergistic alignment of intersectional equity and community psychology ensures respect for all identities and co-creation where everyone has a pathway to what they need. Intersectionality examines power dynamics, transcends communities, practice, and realms of society, and is grounded on application and practice (Collins, 2019). In concert with intersectionality, community psychology demonstrates the understanding that our vastly different histories and traditions mean that not everyone has had the same opportunities or ability to be seen and heard. The recognition mandates heightened awareness of bias, “othering,” and the intentional inclusion of traditionally marginalized perspectives.

“Othering” is a barrier to wellbeing. The many ways in which "othering" harms wellbeing pervades life in the United States and is apparent in the persistence of inequities in health, education, economic status, environmental reality, and domains across the social determinants of health spectrum. Racism itself, and aligned marginalization and humiliation, are traumatic for millions of people and manifest in structures, cultural artifacts, and relationships. Evidence of racism is easily identified in mental and physical health outcomes (Williams, 2016). Community wellbeing research is exponentially more influential when all realms of the social determinants and socioecological perspectives are joined.

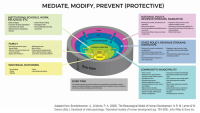

The sociological framework is at the heart of the definition and approach to community wellbeing (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). In Bronfenbrenner's frame, the individual is nested in a series of concentric circles, continually supporting and being bolstered by factors from the family, neighborhood, and community (Fig. 1). Reciprocity across the framework is strengthened by an accurate narrative, deep listening, trust-building, sharing perspectives, and emerging psychological safety, the foundation of social support (Edmonson, 2018). Multilayered, nuanced relationships help people grow, develop, and are the bedrock of civic discourse and meaningful lives.

Relationships are, in turn, influenced by context, cultural attitudes, societal beliefs, and social policy across all domains of the socioecological framework (intrapersonal, interpersonal, institutional/community, and structural/policy) (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). The socioecological model frames the interaction between people and their environments. This dynamic process is crucial to psychological wellbeing. Concomitantly, the reverse is true if one grows up with a deficit narrative in a toxic environment with a dearth of resources (Fig. 2)

Moreover, a healthy ecosystem meets cultural and personal needs, reflects the interests and perspectives of its members, and increases access to health and human services, parks, recreation, and environments that are health-promoting (Marmot & Wilkinson, 2005). A healthy ecosystem is essential to optimal human growth and development (Fig. 1). All areas of the puzzle of a healthy ecosystem are inextricably linked. Social identities, cultural influences, systems, and policies all ground self-perception, behavior, interactions with others, and physical and psychological wellbeing (Harro, 2000).

However, the United States is a society with profound health, education, housing, economic, and environmental disparities (Bullard, 2019; Rothstein, 2018; Wilkerson, 2020). Stigmatization of any traditionally marginalized population has similar implications on human development. Whether Indigenous, African American, or Latino, young or old, gay or straight, woman, man, or nonbinary, with or without a (dis)ability, documented or undocumented, or Muslim, experiences of marginalization are often similar. Enduring the pain of discrimination, the despair of broken dreams, and the oppression of poverty in a land of relative affluence is a struggle (Kite & Whitley, 2016). These disparities present an opportunity to examine the field of community psychology practice, how it is defined, and ensuing implications.

These realizations prompt modifications to a shared definition of community psychology practice presented at the International Conference of Community Psychology in Puerto Rico in 2006 and then adopted by SCRA. The edits reflect the recommended modifications. They may appear minor, but they acknowledge the centrality of co-creation (the artful balance of those directly affected with differing perspectives) and belonging in the work, the imperative to recognize the dignity in all people, the salience of human rights, and the importance of policy and systems. There is an implicit, inclusive social contract at the heart of United States policy doctrine. The United States aspires to be a democratic republic, the perfect union. The vision of pluralism is intrinsic to community psychology. Nevertheless, the dynamic nature of diverse perspectives, various meanings, and assumptions urges us to reflect on power dynamics, connections, and our humanity. The current definition and my suggested revisions to the definition of community psychology practice are indicated below.

Original definition: Community psychology practice is "strengthening the capacity of communities to meet the needs of constituents and help them to realize their dreams in order to promote wellbeing, social justice, economic equity, and self-determination through systems, organizational, and/or individual change" (as presented at the International Conference of Community Psychology in Puerto Rico in 2006 and then adopted by SCRA).

Proposed definition: Community psychology practice is intentional work dedicated to cocreation of an inclusive society recognizing all people's inherent dignity, cogenerating means, and tools to realize their dreams. It promotes wellbeing, human rights, social justice, intersectional equity, and self-determination through all-embracing policies, systems/institutions, organizational, and/or personal change.

Community Psychology: Field, Practice, and Methodologies

This section moves from a high-level overview of a vision of pluralism, aspirational democratic values, and a way to align perspectives, power dynamics, and communities of culture with community practice. Several values inform this definition which will be described in detail below. The rest of this paper outlines my recommended modifications. I will explain each revision to the original definition and its rationale. The premise that the field of community psychology is based on strengthening society must be accompanied by further analysis. The United States is redefining society and who belongs in this circle of concern. Belonging and its aligned attributes are related to the essential ingredient of co-creation. Society and inclusion must be defined to ensure that inclusive society is equitable, supportive, democratic, and conducive to nurturing and implementing numerous perspectives and policies (Nelson & Prilleltensky, 2010).

Recognition of the inherent dignity of all people is essential in a society too quick to ignore a multitude of traditionally marginalized populations. Community psychology is an interdisciplinary, academic arena established as applied psychology and values, lived experience, and co-creation (NeMoyer, Nakash, Fukuda, Rosenthal, Mention, Chambers, Alegría & Trickett, 2020).

This article draws upon the emerging models from civic discourse, public health, environmental justice, racial and ethnic studies, economic justice, and numerous Black, Latinx, Asian, Native/Indigenous, and feminist scholars to support the revised definition of community psychology. The bedrock of this article is the socioecological framework (Bronfenbrenner, 1979), the social determinants of health theory (SDOH) (Marmot & Wilkinson, 2005), and social influences on health (Williams, Yu, Jackson, & Anderson, 1997). These theoretical approaches reckon with current and historical trauma and exploitation of marginalized groups in society. Ethics, justice, and respect are at the heart of community psychology's value of social transformation and the aligned commitment to individual, group, and community empowerment (Prilleltensky, 2019; Rappaport, 1977). The commitment to justice, the value of applied research, multimodal methodologies, and alignment with social policy and practice are embedded in the philosophy of the field.

Trickett (1996) urges the field to mature in his prescient article, “A Future for Community Psychology: The Contexts of Diversity and the Diversity of Contexts.” Contextual factors ground our lives and are predictive of wellbeing. Perhaps this is most evident in the social determinants of health framework (Marmot, & Wilkinson, 2005). The World Health Organization (WHO) defines the SDOH as "the conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age, and the wider set of forces and systems shaping the conditions of daily life, including economic policies and systems development agendas, social norms, social policies, and political systems" (World Health Organization, n.d.). These policies and systems are inevitably shaped by wealth, assets, power, policies, and resources at the local, state, and national levels.

The transdisciplinary field of community psychology builds upon these connected elements. Individual domains may be minimized as "personal responsibility," such as adequate housing, meaningful work, and access to health, education, income, and food security. However, each personal domain has powerful collective implications for society; everyone is inextricably linked, as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. reminds us. The socioecological model, the SDOH framework, and aligned theories, research, and practice bring the proposed revised definition to life. Dimensions of ethnicity, racial identity, religion, culture, and other social contexts deepen the understanding of community psychology practice (Shinn & Toohey, 2003). The experiences of various communities bring discernment to multiple avenues of equity. Equity means giving everyone what they need to succeed with the understanding that not everyone has had the same opportunities or ability to be heard. Effective community psychology practice is grounded by the dynamic interplay of context, wellbeing, equity, identity, culture, deep listening, and policy (Wolff, 2013).

Intersectional equity goes a step further by recognizing and valuing each person’s multiple identities. Equity can be exhibited through an open invitation to participate, unbiased access, and co-creation of entities, institutions, systems, and communities (Powell & Menendian, 2016). Moreover, active engagement, respect, listening to stories, and working to develop pathways to justice is a powerful combination (Powell & Menendian, 2016). The issues of participatory engagement, intersectional identity, belonging, equity, and social justice are rarely connected. The complexity of developing a simultaneously, matrixed model is central to solid community psychology practice.

At this time in the United States, when its egalitarian ethos is frayed, it may be prudent to look toward the predictive work of Mollica (2014) and his international focus on human rights. A disproportionate number of preventable deaths from COVID-19, people locked in cages at the United States-Mexico border, worshipers murdered in synagogues, churches, and mosques, the murders of Black people by police, mass incarceration of Black men, and hatred spewed at Asian communities compels Americans to reconsider the “right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness."

The Modified Definition and Rationale

This section details each concept in the revised definition and corresponding rationale and implications for community psychology practice. This portion of the article is divided into six sections. The initial section outlines the salience of collective efficacy, perspectives on collective efficacy, and alignment with personal and group identity. The interdependencies between community and larger societal structures and frameworks are the themes of the second section. The third section explores the concept of dignity and how it manifests in community psychology. The bedrock of co-creation, partnership, and reciprocity are contemplated in the fourth section. The fifth section examines the concept of human rights and is informed chiefly by international definitions. Finally, the investigation of policy development, implementation, intent, and application is highlighted in the sixth section.

Communal Approach: Collective Efficacy and Co-Creation

The first change to the definition is the insertion of co-creation alongside capacity building. The replacement articulates mutuality and respect; some may see strengthening capacity as the imposition of a dominant ideology or saviorism. Intentional co-creation welcomes lived experience, an egalitarian partnership. Co-creation is an artful balance that bridges differing perspectives and develops, in concert with constituent partners, a shared understanding and language to discuss the challenge and a core set of issues to consider and possible pathways when seeking to effect change. Many collectivist cultures prioritize the wellbeing of the group over that of the individual. Society is a communal setting, making collective efficacy more applicable than self-efficacy (Markus & Kitayama, 2010). Triandis (1995) posits that collectivists prioritize the group. Collectivist thinking and actions are devoted to the family, team, co-workers, religious community, or other affinity groups. The norms of the group determine priorities, unlike individualists who focus on their personal preferences.

Co-creation honors authentic perspectives. Those directly affected are seated at the table to offer their insights and engage in discourse and decision-making. Community psychology, as a field and as a practice, acknowledges power dynamics. Practice is bolstered by co-facilitating, co-managing, deep listening, and co-ordination, recognizing assets and the uniqueness and the complexity of community and differing perspectives. There is a range of psychological, social, cultural, and institutional interactions to attend community work. For example, power relations often perpetuate stereotypes and cede power in many settings to those with advanced degrees (Fox, Prilleltensky, & Austin, 2009). Lived experience is invaluable; as we know, many interventions are deepened by authentic understandings (NeMoyer et al., 2020). Critical reflective practices and ongoing discourse facilitate equity, build relationships, and institute effective, genuine change at the individual, organizational, system, and local community levels (Farr, 2018).

Society, Community, and the Heart of the Field

The second change is replacing the term "communities" with "inclusive society" to reinforce the values of inclusion and collaboration. Society and co-creation are associated with collaboration. Community psychology must take the lead in examining collective action and building enduring commitments that sustain collective wellbeing and transcend narrowly defined communities. Society brings the value of collective efficacy to the fore, elevating individual, community, and policy interdependencies. Historically, the research in psychology and wellbeing has focused on personal wellbeing. Though the field is called community psychology, community psychologists must take a broader societal perspective. Communities are shaped by societal norms and values (Harro, 2000). A panoramic historical view reveals disproportionate implications for traditionally marginalized communities. For example, in the past, communities of color were deprived of the vote by grandfather clauses and “literacy” requirements targeted to oppressed communities. Today active disenfranchisement continues with the passage of numerous federal and state laws limiting access, with innumerable hurdles developed to intentionally disenfranchise voters of color or those with a (dis)ability. Additionally, the reapportionment legislation gives extraordinary power to national policy to reallocate congressional representation, with direct repercussions for community life.

A myopic view of community may be a liability; I, therefore, urge simultaneous examination at the neighborhood and societal realms. For example, racial profiling and the ongoing violence against and murders of people of color are not isolated local events. They are born of a history of dehumanizing narratives, policies that support extraordinary violence and torture of bodies of color, (dis)abled bodies, and a long history of brutality (Alexander, 2010; Wilkinson, 2020). Reciprocity across the socioecological framework is essential in examining the history, resulting policies, socialization, and broad-scale acceptance of dehumanization.

Community psychology argues that externalities (the physical, social, and policy spheres that shape one's life) affect wellbeing in different ways and are central to collective wellbeing (Marmot, 2016). Addressing systemic and structural racism and inequities in the United States and worldwide moves us toward the aspirational goal of becoming a beloved community, a pluralistic community of grace. The societal frame invites the field to paint on a larger canvas embracing the power of systems, policies, and multiple social structures. Valuing the perspectives and assets of countless identities and cultures fosters wellbeing by creating a supportive environment. Community psychology practice aspires to apply principles of inclusion, mattering, and positive relationships across disciplinary perspectives (Prilleltensky, 2019).

As noted in the previous section, collective efficacy magnifies collective power as groups form and engage in collaborative action to achieve mutual goals. The capacity for initiation begins in the self or a group of individuals with a common goal but manifests in a continuum encompassing collective lives. This dynamic is at the heart of co-creation, practice, and powersharing. Co-creation, inclusion, power-sharing, and balance are essential in community psychology practice, paving a pathway of culturally relevant insights. Aligning synergies, welcoming constituent voices, and affiliated systems and policy change are generative aspects predictive of a beloved community. Examining context and inclusion of culture help arrive at a common understanding of shared and divergent meanings, another reason for co-creation. A contextual analysis permits appreciating the salient and interdependent nuances across the socioecological framework, highlighting the texture of relationships and interactions. Perceptions of belonging, relationships, and connections are well-established, psychological wellbeing attributes (Steele, 2011). These findings are significant, given that historically humiliated groups have been intentionally, covertly, or overtly excluded (Bonilla-Silva, 2015) (see Fig. 4).

Research across history, sociology, anthropology, literature, the creative arts, and other academic fields chronicles the struggles of specific groups for inclusion and acceptance, illustrating the importance of mattering to the fabric of humanity (Prilleltensky, 2019). Intersectionality theory shows that being "othered" is not limited to any single characteristic— "othering" can be directed toward any number of attributes, and many individuals have more than one identity that may be simultaneously ill-understood (Crenshaw, 2017). Isolation and sorting of the "other" reinforce stereotypes and narrow categorizations or monolithic views. It also perpetuates hegemonic cultural norms. Intersectional belonging goes a step further; one is invited to co-create the thing one belongs to, making it different from inclusion. The active engagement, respect, seeking the story, and working to develop gateways to justice is a powerful combination (Crenshaw, 2017). A facility with intersectional belonging is vital as the United States and the world struggle to engage hearts, hands, and minds while contending with issues such as climate change and COVID-19.

Recognition of the Inherent Dignity of All

My modified definition of “dignity” is based on the work of Funk, Drew & Baudel (2015) who urge us to move beyond the trappings of socioeconomic status, gender, or race to see and value the inherent dignity and worth of all members of the human family. The third revision, belief in human dignity, is at the core of psychological wellbeing, social connection, and humanity. At this challenging time in United States history, the nation struggles to acknowledge the dignity of all people. Far from a "Black people and white people challenge," historically, the United States has struggled to see value, beauty, and humanity in those who are stigmatized. Many of those stigmatized deviate from the cisgendered, heterosexual, white, Christian, American-born male archetype. The Trail of Tears, the Japanese internment, "Muslim ban," Jim Crow and its repercussions, numerous LGBTQ+ battles in the Supreme Court, and "ban the box, right to employment policies" are but a few examples of racialized policies that are misaligned with the ethos of human dignity. Nevertheless, a field as inclusive as community psychology must put muscle behind a movement to shift the United States from a traumatized nation to one that treats its people with dignity. Police murders and assaults, humiliation because of documentation status, unemployment, food insecurity, or underemployment because of race are all forms of oppression (Franklin, Boyd-Franklin & Kelly, 2006).

Many people who work on social justice focus on one or two identity categories, but injustices affect actors across myriad inequalities. A small but growing number of groups are exploring how gender and sexuality, for example, shape social justice struggles. The work of grassroots activism, participatory engagement, and environmental justice are multidisciplinary, thus including ecofeminism, critical race theory, public health, and community psychology. Numerous forms of inequality perpetuate environmental injustice and shape actors' experiences. This work is strengthened with greater attention to these dynamics, and inclusive intersectionality forms the heart of participatory processes. The richness of different worldviews, disciplines, contexts, cultures, and approaches undergirds the strategy.

The revised definition of community psychology urges us to build on human and communal assets and move from tragedy and trauma to dignity and restoration. Community psychology principles are dedicated to solidifying a path toward wellness and respect (Prilleltensky, 2012). The Belmont Principles, from the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research, were developed because of the vile treatment of African Americans at Tuskegee as subjects for syphilis research (National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research, 1979). A section in the principles, "Respect for Persons," recommends that all influences be plainly stated, operationalized, and acknowledged, and all actions of researchers [and practitioners] denote respect (Campbell & Morris, 2017). These principles provide fodder for contemplation from the multidisciplinary, applied field of community psychology practice, and can intentionally ground respect for the inherent dignity of all people.

According to Shore (2006), respect entails acknowledging and valuing the different skills and experiences within partnerships. Respect also entails a commitment to empowering practices, which include creating participatory processes where all partners have a voice in decision-making and where there is a commitment to translate findings into actual community benefits" (p. 12). Julian, Smith, and Hunt (2017) urge practitioners to develop program and evaluation strategies that include respect for and alignment with the cultures of the communities with which they work.

Respectfully bridging numerous intersectional identities takes time, given that the teaching of United States history across most of the United States is woefully inaccurate and Eurocentric. People must learn more about "the other" to appreciate fully and understand their viewpoints, experiences, story, and assets (DeFreitas, 2019). People in the United States should learn the true history of all their cultures. Textbooks and schools need to be made more inclusive (Annamma, 2016). A comprehension of the magnitude of power and distortions propagated by (hi)storytellers is daunting. Communication is impractical in a sea of faulty assumptions and lies.

For many in the United States, this may be an auspicious time to repair the fabric that has been tattered by time, doubt, lies, conjectures, pain, inaccuracies, insults, assumptions, violence, and abuse (Banks, 2002). It is hard to communicate without a connection. It isn't easy to connect when someone else's, or a community's perceptions and understanding are different from one's own (Baron-Cohen, Tager-Flusberg, & Lombardo, 2013). Building a culture of dignity honors historical facts, challenges, and requires a combined effort to communicate on a tricky subject matter and finally, to rebuild, and heal. Even more challenging may be the discomfort that disrupts the opportunity for possible connections in the short term.

Ting-Toomey (1999) urges self-reflection as we work to reconcile our identity and communicate more thoughtfully across cultures. Her research cautions us to recognize the fact that people overestimate their abilities in social and intellectual domains and, therefore, do not have the awareness to critically examine their performance accurately, thereby overestimating their competence (Kruger, & Dunning, 1999). Ting-Toomey outlines a four-stage process to move toward cultural intelligence: unconscious incompetence, conscious incompetence, unconscious competence, and conscious competence. This paradigm-shift asks us to heighten awareness, expand knowledge, and reflect on our actions, thereby addressing bias and ethnocentrism and advancing toward cultural intelligence (Ting-Toomey, 1999).

Dignity is one pillar of civil society. The field of community psychology explicitly values and highly regards the socioecological framework's individual, group, community, and cultural dimensions. People and communities must have a sense of value, worth, and connection to create meaning, purpose, and believe that they matter (Prilleltensky, 2019). A sense of dignity and belonging offers protection against psychological and social stressors that otherwise precipitate or exacerbate community distress (Thoits, 2011).

Cogenerate Means and Tools

For an organization, network, or movement to thrive in a world where innovation can make a difference, people must share their knowledge and experiences. The fourth revision recognizes the salience of a culture of generativity, a means of sharing concerns, questions, mistakes, experiences, and half-formed ideas. As used in my revised definition, co-creation and the development of generativity builds hope, trust, and possibility. Amid the global cultural upheavals triggered by powerful movements, innovations, and insights that propel activity across domains and fields, people and movements are pushing beyond the status quo toward new paradigms.

Generative organizations, networks, and movements adapt to changing conditions that advance themselves and co-create new societal possibilities. Equity, co-creation, and generativity are not a function of size or type; they are found across domains, fields, issue areas, and networks, large and small—in social justice issues, public organizations, neighborhoods, and informal networks. The distinctive capacities and attributes that make it more likely for organizations, networks, and movements to develop and sustain forward-thinking innovation generate the momentum and sustainability needed to improve wellbeing. Affirming that their perspectives, worldviews, and insights matter and are valued is a natural next step (Prilleltensky, 2019). Concomitantly, the affirmation of the identities of constituents is known to improve outcomes, from civic engagement to academic achievement to life outcomes (Steele, 2011).

Cogeneration welcomes the perspectives of various cultural enclaves and traditionally marginalized communities, making the construct more accessible to millions of people in the United States and around the globe (Powell & Menendian, 2016). From the most senior or outermost policy ring to those closest to the heart of the matter, bidirectional reciprocity is needed; we are all connected. The power of community contagion and its effects are most readily seen in the impact of COVID-19 which is discussed in the sixth section.

Rights and our Values

Restoration of wellness, dignity, belonging, and community engagement, moving toward collective wellbeing, is central to community psychology practice; human rights is the fifth element in the revised definition. Community psychology is built on a foundation of social justice and is aligned with emergent international models (Venkatapuram, 2013).

The modified definition is based on a statement from the United Nations. This statement exalts the inherent human rights and dignity of all human being including the right to liberty, life, freedom from torture, slavery, urging regard for the right to education, free expression, work and many more. s, regardless of race, sex, nationality, ethnicity, language, religion, or any other status. Everyone is entitled to these rights, without discrimination" (United Nations, n. d.). Numerous traditionally marginalized communities argue that the United States has failed to honor their human rights. The modified definition is based on this statement from the United Nations. "Human rights are rights inherent to all human beings, regardless of race, sex, nationality, ethnicity, language, religion, or any other status. Human rights include the right to life and liberty, freedom from slavery and torture, freedom of opinion and expression, the right to work and education, and many more. Everyone is entitled to these rights, without discrimination" (United Nations, n.d.). Numerous traditionally marginalized communities argue that the United States has failed to honor their human rights.

In some quarters of the United States, there is a burgeoning movement to address inequity as exemplified by Black Lives Matter, Stop Asian Hate, increased efforts of disability inclusion, and efforts aimed at removing the check box that asks if job applicants have a criminal record from hiring applications, known as “ban the box.” These efforts, building pathways to equity, highlight numerous examples of inequitable treatment, standards, and access. Human rights abuses indicate a lack of respect for humanity and rights. The United Nations is holding hearings to investigate the United States' human rights violations (Taylor, 2020, June,16). Rappaport notes that "Having rights but no resources and no services available is a cruel joke" (1981, p.13). The United States faces the dilemma of bestowing, restoring, and preserving human rights and aligned resources for its people to exercise these rights.

International law recognizes the rights of all human beings to health, work, and information. Safety and security are at the heart of Maslow's hierarchy of human needs (Maslow & Lewis1987; Kaufman, 2018). For example, international refugee care is premised on a shared understanding of human needs, support, and care necessary for healthy development across the lifespan. However, some advocates for health and human rights, medical professionals, and residents in the United States turn to refugee care standards to advocate for populations in the United States. For example, "Human rights obligations require that migrants' health and wellbeing take priority over national considerations like sovereignty and immigration control"(Willen, Knipper, Abadía-Barrero &Davidovitch, 2017, p. 970). Immigrants’ legal status should not outweigh their human rights. Migrant farmworkers have the right to understand the danger and health consequences of their jobs, environments, earn a decent living, and be treated with dignity. International human rights advocacy may be necessary to enact structural changes for farmworkers and other United States workers. International law may be the entry point for civil and labor rights for those living in the United States (Andrews, Haws, Acosta, Canchila, Carlo, Grant & Ramos, 2019).

Recent research from the Centers for Disease Control reveals shocking drops in life expectancy, particularly for Black, Latinx, and Native/Indigenous populations in the United States, reflecting the consequences of systemic marginalization and living in the shadows (Arias, Tejada-Vera, Ahmad, &Kochanek, July 2021). Arias, Tejada-Vera, Ahmad, and Kochanek reveal that life expectancy in Black and Latinx people has seen an unprecedented two to three- year decline. Researchers purport that the causes are beyond COVID-19 but reflect ongoing degradation in numerous environmental conditions. Health disparities result from inequities in wealth, access to opportunities including education, health care, healthy food, and related societal and ecological conditions predictive of health and wellbeing. Additional manifestations of oppression of traditionally marginalized populations include overwork; lack of living wages, clean water, and adequate housing; environmental hazards; loss of hope; and deficit narratives which have become self-fulfilling prophecies (McEwen, 2021). People can only tolerate so much. Biological embedding and neuroscience document the biological change wrought through the environment.

Biological embedding occurs due to experience and exposure; the environment “gets under the skin” research documents the alterations of the process of development and human biology as a result of experiences in different social environments. Over time, exposure to environmental hazards can influence learning, health, wellbeing, and behavior over the life course (Hertzman, 2012). The stark disparities in morbidity and mortality are an opportunity for community psychology practice to be more engaged in community, societal, and policy discourses, action, and systemic change. Co-creating potential pathways to address the numerous cycles of socialization, unbraiding deficit narratives, and work spanning all levels of civic discourse address structural and systemic causative factors is community psychology practice (Bullard, 2019; Harro, 2000).

The denial of appropriate and culturally fluent, timely, physical, and behavioral health care has and continues to cause tremendous suffering across the United States, as exemplified by more than 650,000 deaths from COVID-19 as of July 2021 (U.S. Center for Disease Control COVID Data Tracker, September 2019). Many of those deaths could have been prevented. Aligned with human rights violations are additional forms of humiliation in the United States directed against those who speak of physical or sexual abuse, mental illness, and (dis)ability. Scant attention is directed to "the other" by policy, community, or anyone other than direct family members and friends (Rozin, Haidt & McCauley, 2008). The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2020 a, b) calls for the alignment of resources for COVID- 19 care and treatment. Unfortunately, and remarkably, the trauma that Black people, Native/Indigenous people, Asian American and Pacific Islanders, and Latinx people face daily are akin to the experiences of refugees in marginalized communities across the globe (Gone, 2007; Mollica, 2014). The lack of clean water, education, constant police presence, inadequate housing, crowded conditions, and poverty are dismayingly common among these populations.

Policies

All-embracing, affirming, evidence-based policies increase the potential of moving wellbeing to scale. The sixth and final revision highlights the need for equitable policy and is evident beyond solely economic policy, as articulated in the initial Community Psychology definition. If the field continues to look exclusively at economic equity, we overlook multiple interdependencies. Equitable policy is evenhanded across all domains. Interdependencies matter.

Moreover, the United States does not and has not ever had a universal functioning, representative democracy (McGhee, 2021). The political system is fractured, and legislative moves over the past two decades continue to dismantle "government for the people, by the people." The system looks more like government for some people by those chosen to affirm an entitled class. Disenfranchisement from policy, systems, and communities leaves individuals alone to make a way forward. COVID-19's stay-at-home guidance has made the isolation profound for many.

Community psychology, a collective endeavor, can ground advocacy and systems change efforts (Scott & Wolfe, 2014). Community psychologists build community. Shinn and Toohey (2003) urge us to recognize the value of context, interdependence, adaptive capacity, building relationships, promoting collective efficacy, and bolstering group norms. Externalities, context, policies, systems, and narratives matter and are predictive and/or instrumental in understanding population-level action, influences, and wellbeing (Rappaport, 2000). Despite the threat of COVID-19, many parts of the United States and under-represented enclaves see hope in civic engagement and make it a priority to participate in the political process by voting even though access to voting is systematically denied. Ongoing litigation on voting laws and ethics, contested for centuries, deprives those in most need of social justice, such as those with (dis)abilities, the elderly, immigrants, and those of African, Latinx, Native/Indigenous, and Asian and Pacific Islander ancestry (Baccini, Brodeur, & Weymouth, 2021; McGhee, 2021). Gerrymandering continues as the 2020 census data reveal increased diversity across the United States.

Public policy is no panacea, is not always designed inclusively, and is inconsistently implemented across jurisdictions. Moreover, if policy is well-conceived, there are still questions of interpretation, staff capacity, bias, and the decisions on revenue allocation to move to scale.

Policy has been used as a wedge, as evidenced by "law and order" policies resulting in overincarceration of people of color, redlining, restrictive voting laws in Georgia, and the Japanese internment during World War II (McGhee, 2021). Head Start, one of the most well-respected policies in the country, is chronically underfunded. The policy debate on national health insurance that denies coverage for pre-existing conditions is an insult to every person with a (dis)ability, nearly 25% of the United States population. Restrictive and punitive policies obstruct wellbeing and have toxic effects (Wilkinson & Pickett, 2018). Historically and today, United States policy has had devastating implications for traditionally dishonored communities (Robles, Leondar-Wright, Brewer, & Adamson, 2006; Rothstein, 2018; Wilkerson, 2020).

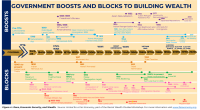

Figure 4 depicts the extensive history of extraordinary, racialized policies in the United States as exhibited in the lower section of the figure, the largest in the diagram. These racist policies contrast with the few policy amendments at the top of the figure where the United States intentionally developed policies to redress systemic racism. Noticeably, there are few policies in this section. The middle segment consists of purportedly universal policies. However, the ethics of policies and implementation varies, corresponding to legality of the policy, interpretation, implementation, community norms, and cost implications indicating that "universal implementation" has not occurred. For example, the Homestead Act (1862) illegally took the home, hunting, and farming lands from Native/Indigenous people and gave them to European settlers. The policy disregarded numerous treaties and pushed Native/ Indigenous peoples onto reservations. This horrific act is another example of Native/ Indigenous annihilation in the United States. At the same time, African Americans were denied Homesteader status.

A civil discourse invites those directly affected to be part of the dialog by offering their input, perspective, and guidance. In my modified definition, inclusive policies are culturally fluent and welcome lived experience to policy formation. Issues of access, language, meaning, and implications are explored in a generative, equity-based process. Inclusive policies are dedicated to a supportive, developmental dialog, clear shared definitions, and equitable implementation. Inclusive policies align with data from multiple sources, including participatory community research, lived experience, qualitative and quantitative data, evaluation of pilots, and insights on implications. Inclusive policy promotes wellbeing (Adler & Seligman, 2016).

Despite its flaws, the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) which became law in 1990, is an example of inclusive policy. The ADA is a civil rights law that prohibits discrimination against individuals with (dis)abilities in all areas of public life, such as jobs, schools, and transportation. The purpose of the law is to ensure that people with (dis)abilities have the same rights and opportunities as people without them. The ADA extends civil rights protections to individuals with (dis)abilities like those provided based on race, color, sex, national origin, age, and religion. It guarantees equal opportunity for individuals with disabilities in public accommodations, employment, transportation, state and local government services, and telecommunications (ADA National Network, 2021).

The field of anthropology has much to offer to the development of inclusive policy. The American Anthropological Association’s (AAA) "Ethic" recommends consideration of potential unintended consequences and long-term impacts on individuals, communities, identities, tangible and intangible heritage, and environments (American Anthropological Association, 2012). A "do no harm" approach may be instructive (Campbell & Morris, 2017).

The American Anthropological Association's (2012) conceptualization of risk requires careful deliberation of possible unintended effects before any work begins and cautions against universalistic assumptions of what is beneficial to others (Campbell & Morris, 2017). Similarly, Shore (2006) reminds us that "individuals and/or groups have varied interpretations of what constitutes a benefit" (Shore, 2006, p.12). In thinking about what constitutes a community benefit, researchers and policymakers need to be self-reflective, value lived experience and community voice, and continually be aware of context. Risks and benefits are relative. "Nothing about us without us" is the byword of inclusive policy (Charlton, 2000).

Community psychology is in an existential crisis as the world confronts the COVID-19 pandemic, hundreds of millions across the globe flee civil unrest and violence, and the devastating implications of climate change become apparent. In 2020, more than 79 million people were forced to leave their homes (UNHCR, 2020). The United Nations estimates that disasters and climate change will displace more than 200 million people; the 2021 devastation of Hurricane Ida is an example. With the international pressure building to recognize human rights and climate change and the United States’ social, economic, political, and health systems being strained, humanitarian relief and community psychology are desperately needed. Both fields center on community healing, co-creation, and practice. Internationally, humanitarian assistance ensures that people have the necessary security, safety, clean water, food, shelter, and sanitation.

The crisis before us is daunting. The United States has seen millions of COVID-19 infections (U.S. Center for Disease Control COVID Data Tracker, September 2021). Clean running water, needed for handwashing, is not available to many families in places such as Flint, Michigan, or the Navajo Nation (U.S. Water Alliance, November 2019). Moreover, more than six million homes in the United States are substandard (National Center for Healthy Housing, 2021). Nearly one million people are homeless, which is likely to increase at the end of the eviction moratorium as benefits are terminated (Bauer, 2020). Twenty percent of United States households report being food insecure (Schuetz, 2020). Access to traditional health care is threatened in a nation where the prevention of infectious disease and the medical care of the seriously ill has traditionally been a national concern. The long-term future of the Affordable Care Act is again in question. The necessity of national health policy, care, and access are starkly portrayed by COVID-19; vulnerabilities are laid bare (Rosenthal, Goldstein, Otterman, & Fink, 2020). Health disparities are aligned with income and wealth disparities, as seen in the devastating impact of COVID-19 on the United States economy (Darity & Mullen, 2020; McGhee, 2021).

Chronic stress caused by racism has a cascade of adverse health outcomes, from high blood pressure, heart disease, immunodeficiency, and vulnerability to viruses such as COVID-19 (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2020 a, b). Racism and sexism endured by Black women contribute to the alarmingly high rates of maternal and infant mortality and morbidity (Geronimus, Bound, Waidmann, Rodriguez, & Timpe, 2019). Unceasing vigilance is antithetical to wellbeing and far beyond the purview of an intervention (Williams, 2016). Stress is a predictor of increased behavioral health challenges, and the mental health of traumatized people is a serious problem (Mollica, 2014). However, the history of policies and systems in the United States, associated racism, humiliation, and discrimination has justified neglect, exploitation, and abuse, permanently marginalizing generations of Black, Brown, Indigenous, LGBTQ, and (dis)abled people (Bonilla-Silva, 2006).

These challenges have persistently been unrecognized out of the assumption that immigrants, refugees, and people of color should not have better neighborhoods, health care, or other amenities. Associated vocational and educational activities are woefully inadequate (Mollica, Brooks, Ekblad, & McDonald, 2015). Community psychology as an applied discipline, in partnership with other domains and the consistent leadership of constituents, must work seamlessly with communities to redirect, reimagine, and reform systems towards producing health and wellbeing rather than marginally preventing or perpetuating conditions of oppression. If there is the will, there is collective power and exponential potential in partnership. The time is now; the issue is urgent.

Conclusion

Our nation was born in genocide when it embraced the doctrine that the original American, the Indian, was an inferior race. Even before there were large numbers of Negroes on our shore, the scar of racial hatred had already disfigured colonial society. From the sixteenth century forward, blood flowed in battles over racial supremacy. We are perhaps the only nation that tried to wipe out its indigenous population as a matter of national policy. Moreover, we elevated that tragic experience into a noble crusade. Indeed, even today, we have not permitted ourselves to reject or feel remorse for this shameful episode. Our literature, our films, our drama, our folklore all exalt it. Our children are still taught to respect the violence, which reduced a red-skinned people of an earlier culture into a few fragmented groups herded into impoverished reservations (Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, in Dyson &Jagerman, 2000, p. 38).

The United States is acclimated to inequity and the devaluation of "the other." Tragically and too often, othering, oppression, and blatant murders are ignored, excused, and, at times, celebrated (Wilkerson, 2020). The lives of the "inferior classes" of people have become vilified in destructive narratives, policies, and systems across the United States. The braiding of flawed thinking at the policy table and significant structural and systemic inaccuracies leave the field of community psychology with an opportunity to rethink the direction, augment academic approaches, and re-examine the meaning of aligned practice.

Emerging literature outlines the amplified psychological stress resulting from "othering," discrimination, and the process of acculturation without stereotypical poverty (Colen et al., 2018). Who we are - as a field, as practitioners, as scholars - matters. Are we showing up at a moment that speaks to the essential life-force of the field? Can we learn together, co-create, and develop respectful, thoughtful discourse as colleagues and with community that this moment requires? Definitions do matter. Perhaps most important is how we define ourselves as deep listeners, servant leaders, and facilitators with the capacity to bridge and translate theory to practice, to impact. Moving comprehensive equity-informed research to policy and practice is followed by implementation, technical assistance, and equity evaluation (Wandersman et al., 2008). Sociopolitical constructs also matter: definitions are at the heart of a trajectory with potent, powerful implications (Mollica, 2014; Prilleltensky, 2019; Wilkinson & Pickett, 2019).

Community psychology research is rich with the constructs and concepts of essential human needs, safety, security, meaning, and purpose in life (Jason et al., 2019). The alignment between community psychology, Sen's (2002) freedoms, and agency, Nussbaum's (2003) hope for a life that is fully human, and emerging research on positive youth development are examples of the grounding of hope (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2019; Shinn, 2015). However, United States policy and systems are often dictated by rigidly defined silos and financing streams; people in the United States are obliged to work in siloed domains, disciplines, and processes (Pittman & Irby, 2007). Compartmentalization is perilous; connectivity is often the catalyst of movement-building stimulated by belonging and co-creation.

Community psychology as a discipline and practice must braid these strands into a comprehensive network, thereby making health, wellbeing, and healing possible. The trauma endured by Black people, Native/Indigenous people, Asian American and Pacific Islanders, Latinx, and (dis)abled people is akin to that of refugees in marginalized communities across the globe (Gone, 2007; Mollica, 2014). The revised definition and aligned practice approaches bolster strategies, tactics, rationale, and the possibility of systems and policy changes, especially those related to all ecosystem elements that ground wellbeing and address systemic racism and ableism; this is the work of the community psychologist. The prioritization of systems and policy work enhances community healing, acknowledgment, and collective efficacy. Models that build on community assets and consistently advocate for culturally fluent physical and behavioral practices and supports are crucial. Prevention and avenues toward healthy housing and environmental justice that span all elements of the social determinants of health are the promise and predict improvement over time.

Multiple levers, strategies, and inputs are needed to build more vital generative movements and networks as part of a broader, social justice ecosystem. The ecosystem is comprised of healthy neighborhoods, housing, engaged residents, community cohesion, and numerous efforts that build community. This rich tapestry is at the heart of community psychology practice. Safe, sanitary, healthy, well-constructed housing and neighborhoods with adequate lighting, green spaces, walking, and cycling areas, accessible to all abilities, are paramount. Urban design is an upstream community psychology model aligned with creative place-making in public health and urban studies.

Community power, engagement, and direct participation in determining one's destiny are crucial at this moment. Community psychology practice is dedicated to strengthening the capacity and co-creation of an inclusive society that recognizes all people's inherent dignity, cogenerating means and tools to realize dreams. It promotes wellbeing, human rights, social justice, intersectional equity, and self-determination through all-embracing policies, systems/institutions, and/or organizational and personal change. Community psychology has the theory, tools, ethos, and power to be a foundational passing gear to build policies, systems, and equitable implementation. However, we must seize the opportunity, or it could be lost for a generation or perhaps, forever. Our society must reflect the inherent dignity of all people in multiple pathways to social justice and equity. We delay at our collective peril. The time is now; let us get to work.

References

ADA National Network (year).https://adata.org/learn-about-ada#:~:text=The%20Americans%20with%20Disabilities%20Act%20(ADA)%20became%20law%20in%201990,open%20to%20the%20general%20public.

Adler, A., & Seligman, M. (2016). Using wellbeing for public policy: Theory, measurement, and recommendations. International Journal of Wellbeing. 6 (1), 1-35.

Alexander, M. (2010). The new Jim Crow: Mass incarceration in the age of colorblindness. New York, NY: The New Press.

American Anthropological Association. (2012, November 1). 1. Do no harm. AAA Ethics Forum.http://ethics.americananthro.org/ethics-statement-1-do-no-harm/

Andrews, A. R. III, Haws, J. K., Acosta, L. M., Acosta Canchila, M. N., Carlo, G., Grant, K. M., & Ramos, A. K. (2019). Combinatorial effects of discrimination, legal status fears, adverse childhood experiences, and harsh working conditions among Latino migrant farmworkers: Testing learned helplessness hypotheses. Journal of Latinx Psychology volume(number), pages https://doi.org/10.1037/lat0000141

Annamma, S. A. (2016). DisCrit: Disability studies and critical race theory in education. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Arias, E., Tejada-Vera, B., Ahmad, F., &Kochanek, K, (2021, July). Provisional Life Expectancy Estimates for 2020 Vital Statistics Rapid Release. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/index.htm. Report No. 015.

Baccini, L., Brodeur, A. & Weymouth, S. (2021). The COVID-19 pandemic and the 2020 US presidential election. Journal of Population Economics, 34, 739-767. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-020-00820-3

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York, NY: Freeman.

Banks, J. A. (2002). Race, knowledge construction, and education in the USA: Lessons from history. Journal of Race, Ethnicity and Education, 5 (1), 7-28.

Baron-Cohen, S., Tager-Flusberg, H., & Lombardo, M. (Eds.). (2013). Understanding other minds: Perspectives from developmental social neuroscience. London: Oxford University Press.

Bauer, L. (2020, May 12). The COVID-19 crisis has already left too many children hungry in America. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2020/05/06/the-covid-19- crisis-has-already-left-too-many-children-hungry-in-america/

Bond, M. A. (2016). Leading the way on diversity: Community psychology’s evolution from invisible to individual to contextual. American Journal of Community Psychology, 58(34), 259-268.

Bonilla-Silva, E. (2006). Racism withiout racists: Color-blind racism and the persistence of racial inequality in the United States. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Bonilla-Silva, E. (2015). The structure of racism in color-blind, “post-racial” America. American Behavioral Scientist, 59(11), 1358-1376.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. A. (2006). The Bioecological Model of Human Development. In R. M. Lerner & W. Damon (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Theoretical models of human development (pp. 793-828). John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Bullard, R. (2019). Addressing environmental racism. Journal of International Affairs, 73(1), 237-242.https://doi.org/10.2307/26872794

Campbell, R., & Morris, M. (2017). Complicating narratives: Defining and deconstructing ethical challenges in community psychology. American Journal of Community Psychology, 60(3-4), 491-501. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12177

Charlton, J. I. (2000). Nothing about us without us: Disability oppression and empowerment. Oakland, CA: University of California Press.

Colen, C. G., Ramey, D. M., Cooksey, E. C., & Williams, D. R. (2018). Racial disparities in health among nonpoor African Americans and Hispanics: The role of acute and chronic discrimination. Social Science & Medicine, 199, 167-180.

Collins, P. H. (2019). Intersectionality as critical social theory. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Crenshaw, K. (2017). On intersectionality: Essential writings. City, State: The New Press.

Darity, W. A., Jr., & Mullen, A. K. (2020). From here to equality: Reparations for Black Americans in the twenty-first century. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

DeFreitas, S. C. (2019). African American psychology: A positive psychology perspective. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company.

Dyson, M. E., &Jagerman, D. L. (2000). I may not get there with you: The true Martin Luther King, Jr. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster.

Edmondson, A. C. (2018). The fearless organization: Creating psychological safety in the workplace for learning, innovation, and growth. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Farr, M. (2018). Power dynamics and collaborative mechanisms in co-production and co-design processes. Critical Social Policy, 38(4), 623-644. https://doi .org/10.1177/0261018317747444

Fox, D., Prilleltensky, I., & Austin, S. (2009). Critical psychology for social justice: Concerns and dilemmas. In D. Fox, I. Prilleltensky, & S. Austin (Eds.), Critical psychology: An introduction (pp. 3-19). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Ltd.

Franklin, A. J., Boyd-Franklin, N., & Kelly, S. (2006). Racism and invisibility: Race-related stress, emotional abuse and psychological trauma for people of color. Journal of Emotional Abuse, 6 (2-3), 9-30.

Funk, M., Drew, N., &Baudel, M. (2015, October 10). Dignity in mental health. Occoquan, VA: World Federation for Mental Health. https://www.who.int/mental health/world-mental-health-day/paper wfmh wmhd2015.pdf

Geronimus, A. T., Bound, J., Keene, D., & Hicken, M. (2007). Black-white differences in age trajectories of hypertension prevalence among adult women and men, 19992002.Ethnicity & Disease, 17(1), 40-49.

Gone, J. P. (2007). “We never was happy living like a Whiteman”: Mental health disparities and the postcolonial predicament in American Indian communities. American Journal of Community Psychology, 40(3-4), 290-300. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-007-9136-x

Harro, B. (2000). The cycle of socialization. In M. Adams, W. Blumenfeld, R. Castañeda, H. Hackman, M. Peters, & X. Zúñiga (eds) Readings for diversity and social justice: An anthology on racism. New York, NY: Routledge.

Hertzman, C. (2012). Putting the concept of biological embedding in historical perspective. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(Supplement 2), 17160-17167.

Jason, L. A., Glantsman, O., O'Brien, J. F., & Ramian, K. N. (2019). Introduction to Community Psychology: Becoming an Agent of Change. Montreal: Rebus. https://www.communitypsychology.com/cptextbook/

Julian, D. A., Smith T., & Hunt, R. A. (2017). Ethical challenges inherent in the evaluation of an American Indian/Alaskan Native Circles of Care project. American Journal of Community Psychology, 60(3-4), 336-345. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12192

Kaufman, S. B. (2018). Self-actualizing people in the 21st century: Integration with contemporary theory and research on personality and wellbeing. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 0022167818809187.

Kite, M. E., & Whitley Jr, B. E. (2016). Psychology of prejudice and discrimination. New York and London: Routledge.

Kruger, J., & Dunning, D. (1999). Unskilled and unaware of it: How difficulties in recognizing one's own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(6), 1121.

Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (2010). Cultures and selves: A cycle of mutual constitution. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 5(4), 420-430.

Marmot, M. (2016). The health gap: The challenge of an unequal world. New York, NY: Bloomsbury Press.

Marmot, M., & Wilkinson, R. (Eds.). (2005). Social determinants of health. Oxford: Oxford Press.

Maslow, A., & Lewis, K. J. (1987). Maslow's hierarchy of needs. Salenger Incorporated, 14(17), 987-990.

McEwen, B. S. (2012). Brain on stress: How the social environment gets under the skin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109 (Supplement 2), 17180-17185.

McGhee, H. (2021). The sum of us: What racism costs everyone and how we can prosper together. New York, NY: One World/Ballantine.

Mollica, R. F., Brooks, R., Ekblad, S., & McDonald, L. (2015). The new H5 model of refugee trauma and recovery. In J. Lindert & I, Levav (Eds.), Violence and mental health (pp. 341-78). New York, NY: Springer.https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-8999-8 16

Mollica, R. (2014, September). Caring for Refugees and other highly traumatized persons and communities. The New H5 Model: Trauma and Recovery: A summary. Harvard Program in Refugee Trauma, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School.http://hprt-cambridge.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/THE-NEW-H5-MODEL-TRAUMA-AND-RECOVERY-09.22.14.pdf

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2020, May 19). International Human Rights Network of Academies and Scholarly Societies Call for a Human Rights- Based Approach to COVID-19. https://www.internationalhrnetwork.org/uploads/9/9/6/8/99681624/covid-19 and human rights.pdf

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (June 2020). COVID-19 and Black communities: A workshop.https://nasem.zoom.us/j/91304300307

National Center for Healthy Housing. Substandard Housing.https://nchh.org/resources/policy/substandard-housing/

National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research. (1979). The Belmont Report: Ethical principles and guidelines for the protection of human subjects of research. https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and- policy/belmont-report/index.html

Nelson, G., & Prilleltensky, I. (Eds.). (2010). Community psychology: In pursuit of liberation and wellbeing. (2nd ed.). London, England: Palgrave/Macmillan.

NeMoyer, A., Nakash, O., Fukuda, M., Rosenthal, J., Mention, N., Chambers, V. A., Delman, D., Perez G., Jr., Green, J. G., Trickett, E., &Alegría, M. (2020). Gathering diverse perspectives to tackle “wicked problems”: Racial/ethnic disproportionality in educational placement. American Journal of Community Psychology, 65(1-2), 44-62. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12349

Nussbaum, M. C. (2003). Capabilities as fundamental entitlements: Sen and social justice. Feminist Economics, 9(2-3), 33-59. https://doi.org/10.1080/1354570022000077926

Pittman, K. J., & Irby, M. (2007). Engaging every learner: Blurring the lines for learning to ensure that all young people are ready for college, work, and life. In A. M. Blankstein, R. W. Cole, & P. D. Houston (Eds.), Engaging EVERY learner (pp. 119-146). Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin/SAGE. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483329383.n7

Powell, J. & Menendian, S. 2016. The problem of othering: Towards inclusiveness and belonging. Othering and Belonging 1: 14-39.

Prilleltensky, I. (2012). Wellness as fairness. Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Wellbeing Research, 49(1), 1-21.

Prilleltensky, I. (2019). Mattering at the intersection of psychology, philosophy, and politics. American Journal of Community Psychology, 65(1-2), 16-34.

Rappaport, J. (1977). Community psychology: Values, research and action. New York, NY: Rinehart and Winston.

Rappaport, J. (1981). In praise of paradox: A social policy of empowerment over prevention. American Journal of Community Psychology, 9(1), 1-21.

Rappaport, J. (2000). Community narratives: Tales of terror and joy. American Journal of Community Psychology, 28, 1-24.

Robles, B., Leondar-Wright, B., Brewer, R., & Adamson, R. (2006). The color of wealth: The story behind the U.S. racial wealth divide. New York, NY: The New Press.

Rosenthal, B.M., Goldstein, J., Otterman, S & Fink, S. (2020, July 2). A stark factor in beating Covid: Which hospital you can afford. New York Times, p. A1. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/01/nyregion/Coronavirus-hospitals.html.

Rothstein, R. (2018). The color of law : A forgotten history of how our government segregated America. New York, NY: Liveright Publishing Corporation.

Rozin, P., Haidt, J., & McCauley, C. R. (2016). Disgust. In M. Lewis, J. M. Haviland-Jones, & L. F. Barrett (Eds.), Handbook of emotions (4th ed., pp. 815-834). New York and London: The Guilford Press.

Sen, A. (2002). Why health equity? Health Economics, 11(8), 659-666. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec .762

Schuetz. J., (2020, March 12, 2020). America’s inequitable housing system is completely unprepared for coronavirus. Brookings Institute, Washington, D.C. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/the-avenue/2020/03/12/americas-inequitable-housing-system-is-completely-unprepared-for-coronavirus/

Scott, V. C., & Wolfe, S. M. (Eds.). (2014). Community psychology: Foundations for practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Sen, A. (2002). Why health equity? Health Economics, 11(8), 659-666. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec .762

Shinn, M. (2015). Community psychology and the capabilities approach. American Journal of Community Psychology, 55(3-4), 243-252. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-015-9713-3

Shinn, M., & Toohey, S. M. (2003). Community contexts of human welfare. Annual Review of Psychology, 54(1), 427-459.

Shore, N. (2006). Re-conceptualizing the Belmont Report: A community-based participatory research perspective. Journal of Community Practice, 14 (4), 5-26.

Steele, C. M. (2011). Whistling Vivaldi: How stereotypes affect us and what we can do. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company.

Stevens, H. Bahrampour, T, & Mellnik, T. (2021, April 14). Why your state might lose or gain clout in Congress after the census is released. The Washington Post. https://www.washmgtonpost.com/politics/mteractive/2021/how-apportionment-works/?utm_campaign=wp_post_most&utm_medium=email&utm_source=newsletter&wpisrc=n l_most&carta-url=https%3A%2F%2Fs2.washingtonpost.com%2Fcar-ln-tr%2F31de8a7%2F607714f99d2fda1dfb4ef878%2F5977325bae7e8a6816e29af9%2F9%2F66%2F607714f99d2fda1dfb4ef878

Ting-Toomey, S. (1999). Communicating across cultures. New York, NY : Guildford Press.

Tajfel, Henri. 2010. Social Identity and Intergroup Relations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Taylor, A. (2020, June, 16). U.N. Human Rights Council to turn attention on ‘systemic’ racism in United

States. The Washington Post https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2020/06/16/un-human-rights-council-turn-attention-systemic-racism-united-states/

Thoits, P. A. (2011). Mechanisms linking social ties and support to physical and mental health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 52(2), 145-161. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022146510395592

Triandis, H. C. (1995). New directions in social psychology. Individualism and collectivism. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Trickett, E. J. (1996). A future for community psychology: The contexts of diversity and the diversity of contexts. In T.A. Revenson, et al. (Eds.), A quarter century of community psychology. Boston, MA: Springer.

Trickett, E. J. (2009). Multilevel community-based culturally situated interventions and community impact: An ecological perspective. American Journal of Community Psychology,43(3-4), 257-266.

United Nations. (n.d.). Human rights. https://www.un.org/en/global-issues/human-rights

United Nations High Commission on Refugees. (2020, June 18). Figures at a glance. United Nations Refugee Agency.https://www.unhcr.org/en-us/figures-at-a-glance.html

U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). COVID Data Tracker. (2019, September).httpsT/ęovdędcgovęovįd-dataHraęker/Ėdatatraęker-home

U.S. Declaration of Independence. Second paragraph (1776).

U.S. Water Alliance (2019, November). Dig Deep, Close the Water Gap: A National Action Plan. https://www.digdeep.org/close-the-water-gap

Venkatapuram, S. (2013). Health justice: An argument from the capabilities approach. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

Wandersman, A., Duffy, J., Flaspohler, P., Noonan, R., Lubell, K., Stillman, L., Blachman, M., Dunville, R., & Saul, J. (2008). Bridging the gap between prevention research and practice: The interactive systems framework for dissemination and implementation. American Journal of Community Psychology, 41 (3-4), 171-181. https://doi .org/10.1007/s 10464-008-9174-z

Schultz, S. (2005, December). Calls made to strengthen state energy policies. The Country Today, 1A, 2A. Washington Post https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2020/06/16/un-human-rights-council-turn-attention-systemic-racism-united-states/

U.S. Center for Disease Control COVID Data Tracker (Sepember, 2019) https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#datatracker-home

U.S. Water Alliance (Nov, 2019). Dig Deep, Close the Water Gap: A National Action Plan. https://www.digdeep.org/close-the-water-gap.

Wilkerson, I. (2020). Caste: The origins of our discontents. New York, NY: Random House.

Wilkinson, R., & Pickett, K. (2019). The inner level: How more equal societies reduce stress, restore sanity and improve everyone's wellbeing. London: Penguin Press.

Willen, S. S., Knipper, M., Abadía-Barrero, C. E., &Davidovitch, N. (2017). Syndemic vulnerability and the right to health. The Lancet, 389(10072), 964-977.

Williams, D. R., & Cooper, L. A. (2019). Reducing racial inequities in health: using what we already know to take action. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(4), 606.

Williams, D. R. (2016, June). Measuring discrimination resource.

https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/davidrwilliams/files/measuring_discrimination_resource _june_2016.pdf

Williams, D. R., Yu, Y., Jackson, J. S., & Anderson, N. B. (1997). Racial differences in physical and mental health: Socio-economic status, stress and discrimination. Journal of health psychology, 2(3), 335-351.

Wolff, T. (2013). A community psychologist’s involvement in policy change at the community level: Three stories from a practitioner. Global Journal of Community Psychology Practice, 4(2), xx-xx. Retrieved from http://www.gjcpp.org/.

World Health Organization. (n.d.). Social determinants of health. https://www.who.int/social determinants/sdh definition/en/

Figure 1 |

Figure 2 |

Figure 3 |

Figure 4 |

Christine Robinson

Christine Robinson