Modernity has disembodied and dissociated psychological subjectivity. It has significantly affected the capacity of individuals and communities to engage proactively in their worlds. Racism is part of modernity’s system of social control and is embedded as part of a Colonial Matrix of Power (CMP) (Quijano, 2000). Epistemic (epistemological) hegemony is an underlying assumption that is rarely called into question and is the glue that sustains the matrix. Community Psychology is based on assumptions rooted in the CMP, and its methodologies and conclusions must be called into question. This article is intended as an intervention to stop the ongoing harm of the CMP. Non-modernity is a starting point for challenging the CMP, to identify its false narratives and to recognize different epistemologies and ontologies. Non-occupied space is a condition for embodiment, the re-membering (re-integration) of the disembodied parts (Anzaldua, 2015). Out of this space emerge denormalized stories that simultaneously reveal how the matrix of power functions and re-member the village (i.e. epistemologies, ontologies, and social relationships delegitimized and silenced by conquest and violence).

Please click here to access the PDF version of this article, including images.

Author's Note: This article does not reflect primary and secondary authorship. Instead, it is a co-creation of both authors, individually and collectively. We also want to acknowledge that we are both part of dialogue circles that, while not directly working on this article, had significant impacts on the authors’ perspectives. Additionally, we would like to acknowledge the contributions of Ramy Barhouche and Christopher Sonn in the development of the ideas that shaped this writing.[1]

Part One: A Challenge and Calling to Community Psychologists

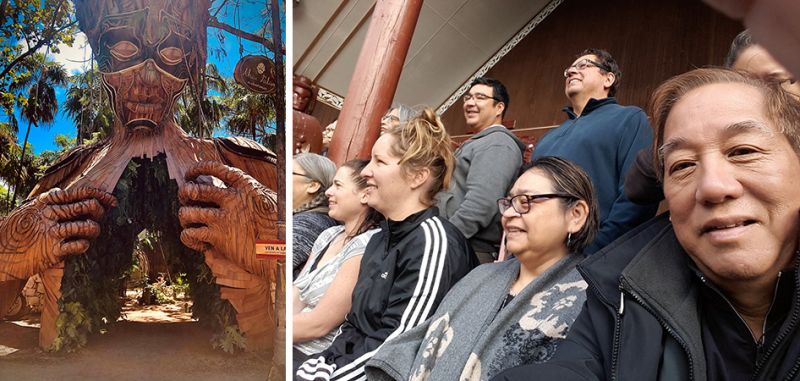

In this moment of various fracturing and inevitable change, including the globally recognized killing of George Floyd, Black Lives Matter, planetary climate crisis, the COVID-19 global pandemic, and the most recent news of the U.S. Supreme Court leaked draft to overturn Roe v. Wade, which would turn back needed shifts in support of women’s rights . . . What are the most urgent issues facing community psychology today? We suggest that the following issues must be addressed.

[Unknown Author [Online Image] (2022): https://twitter.com/oliviaugino/status/1268408713565671424]

How do we get beyond ways of thinking that are intimately connected/intertwined to existing ways of being, including within ourselves? What kind of space can nurture and support a new culture of politics that empowers groups and individuals to think and imagine “otherwise” and enables a process of construction of another world. A space that is an incubator of new frameworks of research, teaching, and application (Andreotti & Dowling, 2004).

…unless a radical shift in paradigm praxis takes place in the field of counseling psychology, it will remain both irrelevant and a tool for further colonization of Indigenous/Tribal people as well as for those who seek an existence based on peace for all beings on the planet. . . . I have come to a standstill in my career, presented with an irreconcilable difference that must be addressed if this field and the praxis that underlies its basic assumptions are to be considered a viable avenue in making a better world for all (Grayshield, 2010).

Remembering Radical Community Psychology

These are not new questions or new challenges.

In the United States, critical psychology, Black psychology, liberation psychology, and other threads within the field have long recognized the “failure” or incapacity of mainstream psychology to acknowledge the inequities of the broader psychosocial world and to identify the systemic and epistemic sources of those inequities as part of its practices. Notions of a more radical approach have been present for many generations, particularly during times of and in conjunction with different social-political movements. Community psychology itself arose from the political movements of the 1960s. The Swampscott Conference was held in Massachusetts in 1965.[2] The Association of Black Psychologists (ABPsi) was founded in San Francisco in 1968.[3] The Radical Therapist was published in New York in 1971.[4] In this publication they wrote:

RT [Radical Therapy] is a way of living, not another “new kind” of therapy that can take its place in the psychotherapy spectrum. RT starts from the awareness that therapy is a social and political event, and moves to the conviction that therapy systems – like many of this country’s institutions—must be changed. (Radical Therapist Collective, 1971; Preface)

More than ten years earlier, Franz Fanon had formulated a Third World model of community psychology, writing Black Skin, White Masks in 1952 and Wretched of the Earth in 1963.[5] Aimé Césaire explicated A Discourse on Colonialism in 1950.[6] Thirty years before Swampscott, Carter G. Woodson explicated the Miseducation of the Negro in 1933.[7] W.E.B. Dubois, in the Souls of Black Folk, identified double consciousness in 1903.[8]

We are not alone, and this article and issue is not just about us. The field is wide and it extends well beyond the academy and beyond the United States.

To connect to other creative outlets on this, we invite you to listen to the audio recording of “Something in the Way of Things (in Town)” by The Roots and Amiri Baraka, within a larger discussion of this poem and author: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/podcasts/147442/something-in-the-way-a-discussion-of-amiri-barakas-something-in-the-way-of-things-in-town. (Poetry Foundation, 2018)

This article is about:

Part Two: Decoloniality and Embodiment

Over the last 30 years (1990-2020) thinkers, writers, activists, and artists have engaged, in different ways, and from different perspectives, in projects to understand and describe the conditions which have emerged in the era of post-decolonization (Mignolo & Walsh, 2018; Wynter, 2015). The concept of decoloniality is attempting to differ from, and go deeper/further than, previous projects of decolonization. The distinction being that decolonization sought to take hold of the state, and decoloniality seeks to uncover the etiology of how we view the world and how the world functions through an in-depth examination of the nature of knowledge, knowledge management, dissemination, and power. In other words, decoloniality pursues epistemological and ontological decolonization, or the decolonization of knowledge and epistemic justice (Dreyer, 2017) as well as Western ways of living (Escobar, 2020). Decoloniality simultaneously challenges Eurocentric ideologies and the dominant imperial Western knowledge systems that have shaped the development of economic, cultural and political systems across the globe; while also reclaiming and legitimizing a pluriverse of knowledge systems and ways of being that have been oppressed.

To clarify the basic concepts of decoloniality that we have found helpful, we provide some descriptions. The core connection here is that these concepts come alive within us and manifest differently, or other-wise, in relationship to the world we inhabit. It is important to note first that, according to Mignolo and Walsh (2018), the three main concepts of Modernity/Coloniality/ Decoloniality work together as a conceptual triad. Decolonial thinking makes it possible to see coloniality. Therefore, we begin with the concept of decoloniality, and then show how modernity and coloniality relate to embodied praxes of decoloniality:

Since these three concepts work together, we draw attention to examples here of how products of modernity also hold aspects of coloniality in their underbelly (in parentheses). Through modernity we have witnessed early characteristics of globalization, including the development of democracy and liberalism, European colonization of the Americas (the New World Project), the spread of Christianity, and the Columbian Exchange which includes industrialized agriculture (the Slave Trade) and Residential Schools (Native American genocide). This period of development came about through the industrial revolution, along with a communications revolution, which is also referred to as the age of ideology and the Scientific Revolution. Modernity contributed to the distinction between those who are civilized and those who are not, but this is not something we will readily see in our daily world, which is why we need to clarify how coloniality manifests within modernity, or what has been referred to as the dark side of Western modernity (Mignolo, 2011).

Layers of disembodiment: Individuals and Organizations/Communities

Our bodies, our subjectivity, are shaped by political, economic, and psychological systems normalized by modernity/coloniality, which means that our experiences are shaped by this landscape, including technologies, dominant narratives, and political economics. All characteristics of our being are, to varying degrees, politicized in every sphere of life, often through a binary lens, including: ability/disability, black/white, male/female, good/bad. All of this influences how we hold and relate to ourselves physically, shapes our emotional landscape, and plays a role in how we experience ourselves individually and in relationship with others.

This world is highly interconnected (a matrix), so it extends (flows) into whole sets of human-designed community systems shaped upon the terms spewing from this dominant narrative and ontology e.g. non-profit/NGOs, government funded programs. This also includes the assumptions embedded within institutions (higher education).

To embody a praxis of decoloniality involves being in a heightened state of awareness and ongoing questioning of our own positionality in terms of the power of choice within varying situations. This feeling has been described as “seeing the world in technicolor”, where we see the shininess of the object in front of us (modernity), but we also see all those who suffered for that object to exist (coloniality). From there, we can also see different options depending our assessment of that situation, discerning how we want to be in relationship to such “objects”, and the necessary actions to choose from as we can see how all our actions are tied to the underlying web of control based on social constructions that maintain the relevance of that object. Ultimately, embodiment of a praxis of decoloniality is understanding our embeddedness within a constant flux of analytic and prospective doing, and centering our awareness on choices of action[11].

Our Unique Positionality Being in the “United States of America”

Our positionality within the United States in the year 2022 is of particular importance in our analysis of our situation and the value and significance of embodying decoloniality. The historical, political, and economic location we are situated within as a country within a larger international landscape has much to do with why we believe this understanding of modernity/coloniality is crucial. While many of us that inhabit this land likely relate to some mix of terms such as: “Native American”, “indigenous”, some version of “ethnic minority”, “Afro-descendent”, “Black”, “immigrant”, or “refugee” from this or another land of which we were forcibly displaced, or voluntarily traversed from, our location of this moment is planetarily political. With all the technology, information, and communication tools we have access to now, we have a choice (and we might argue, a responsibility) to act with this awareness.

Problematizing this situation allows us to see what is behind the curtain. If we do not buy into the American narrative of ourselves, how do we affirm ourselves without re-centering our own selves in the United States? How do we reclaim different parts of who we are, and not see ourselves based on a construction of someone else’s story about us?

People have become inhabitants of this land for many reasons, and many continue to come here under the narrative that this is the land of “opportunity” and “freedom”. There is little consideration paid to the understanding that opportunity in this context, within the lines and federal regulations that have been drawn on this land, required a numbing of our senses to the harms imbedded within such an ideological frame. Those who created this narrative created concepts of freedom and opportunity with the intent to extract and exploit natural and human resources, which required global domination and the taking of many of our ancestors for labor; whose hands were put to the dirty, and often bloody, work of an industrial machine (industrial and technological revolutions). These issues we are grappling with here are about American, particularly North American, imperialism grounded in the machine of global capitalism.

The United States has participated in a long history of oppression and harm (e.g., war) through the agenda of globalization using military, economic, and scientific tools. If we do not take this opportunity to be archeologists of ourselves, to excavate our diasporas and unearth the layers of Eurocentered colonial sediment that is the foundation and source of human misery, we will remain tools of the machine.

It has always been our desire to see outside the box, to think, question, and seek solutions from outside the box. To embody praxes of decoloniality is to ideologically and physically delink/unplug from the machine - this is how to get outside the box. While the term “justice” is a liberal idea that is grounded within the box we wish to escape, if we truly do care about justice, in all its forms[12], then we have a responsibility to understand the ways in which our lifestyles/daily choices maintain the power/domination of the US in larger forces of harm around the world. Let us figure out how to get rid of the box!

Given the history of the development of the United States being grounded in the history of European colonization, when we use the term modernity, we mean it as Euromodernity to specify our knowing that modernity exists around the globe in many different forms depending on the histories of colonization that developed these ideologies on different continents (Mignolo, 2007; 2021; Lowe, 2015). We believe it is important to learn further how modernity/coloniality manifested and maintains its grip at many points and histories around the planet (Royal Institute of Philosophy, 2022).

A. Epistemic Oppression, the CMP, and Disembodiment

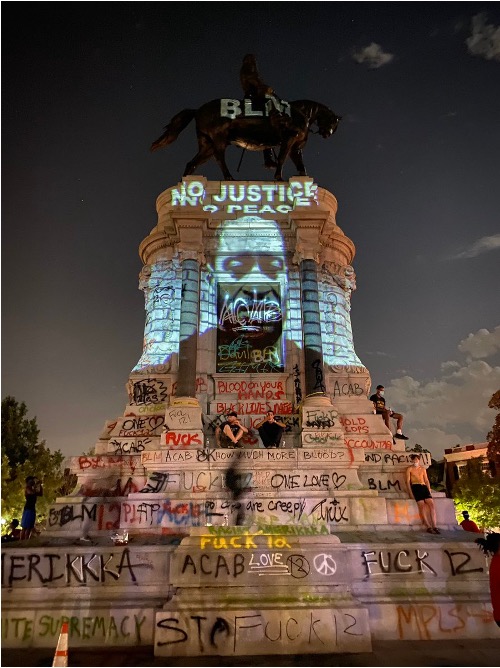

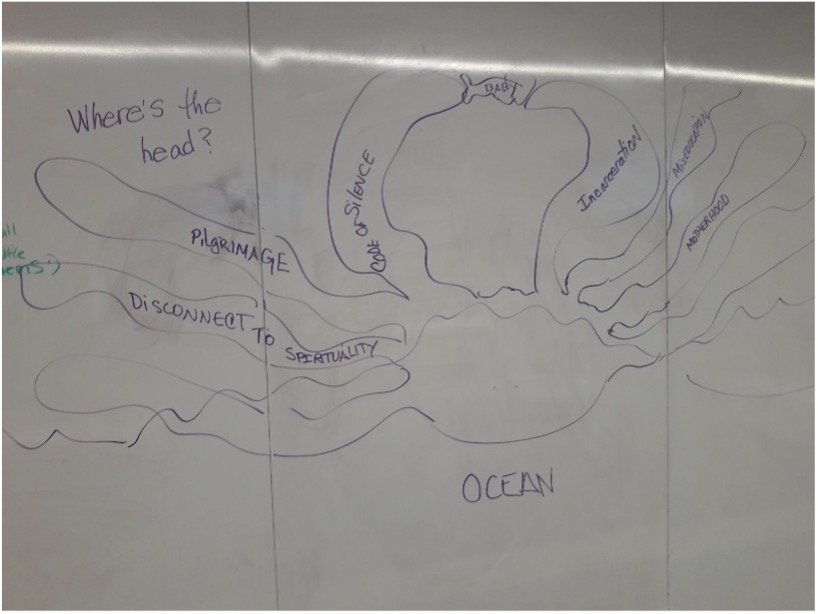

The web of interweaving forces, structures, constructions, narratives, and ways of knowing and being has been called the Colonial Matrix of Power (CMP) (Quijano, 2000). We have experienced and visualized it as the Octopus (Octo).[13] The CMP/Octo is embedded as the framework, the power lines that hold the reality of Modernity/Coloniality together. It affects us as much as it affects the world. As such, the matrix is embedded in our human psychology. In other words, the constructions embedded within the CMP have established known and dominant realities that have influenced our sense of self and our relationships with the world (inter-subjectivities). For some, there is an unravelling of wholeness that follows us throughout our lives. The consequences are that the CMP/Octo is embedded in the fabric of the world and within us simultaneously.

Octopus [Online Image]. Yin, 2015

Understanding the Flows of the CMP/Octo

The CMP/Octo is a stealth-like system of control. A planetary intervention that originated approximately 500 years ago via processes of Eurocentered colonialism, or European political, social, and cultural domination. There is much written about the CMP (Mignolo, 2007; Mignolo & Walsh, 2018; Mignolo, 2021; Quijano, 2000, 2007), so we will not cover this framework in all the details through which many authors have attempted to unpack how it works. However, a summary will be attempted, connecting its relevance to psychology.

The CMP/Octo intervention is a global economic business model of capitalism that intentionally dismantled the existing ways of life and social organization of Mother Earth—“the aim of these tools and institutions [are] to contain and administer all of life itself” (Escobar, 2020, p. 49). The dynamics associated with this continues to do so today and manifest as hegemonic common sense rhetoric, logics, and a system of management manifesting as patriarchy, sexism, heterosexism, racism, ableism, and religious superiority. These isms (among others) are engrained in the fabric of our social norms and institutional practices, all articulated by the CMP/Octo.

The CMP/Octo manifests as a set of assumptions that clarify the epistemological and ontological reality of the Euromodern worldview based on specific domains of management. The four main domains of control include: control of economy (type of economy), control of authority (legal authority/governance), control of gender/sexuality (human/humanity), and control of subjectivity (knowledge/understanding). However, these are not discrete categories of control. They compose a matrix (or Patrix[14]): streams of assumptions that weave through our conception of reality through flows of discourses tied to enunciations (Mignolo, 2021). These intermingling discourses perpetuate the social constructions that shape our understanding of reality, epistemic oppression, and disembodiment.

There are four main assumptions of the rhetoric and logic. First, humans are superior on Earth, indicating that the natural world of the planet exists on a separate plane of existence with a different and separate ontology that is less than the value of humans (i.e., anthropocentrism). Second, “human,” or Man (Sylvia Wynter’s (2015) concepts of Man1 and Man2 are essential here), is central in all domains, providing this concept of human with top authority. Third, “humanity” is based on a hierarchy where people of light/white skin color are human, and everyone else is non-human, which has also been based on religious hierarchies where Christians were humans and non-Christians were non-human. Though this is an oversimplification, it demonstrates the key concepts. Within this third assumption is the fourth, based on the binary subjective groupings of men and women, which is another hierarchical relationship of patriarchy, where men hold the power and women are excluded from it.

While there are exceptions in some places/spaces, some version of all of these assumptions are embedded within our dominant onto-epistemological reality, our social, political and governing systems. Essentially, being a system of control, where the outputs are predictable, the nature of the CMP/Octo is hierarchy upon hierarchy upon hierarchy… To get at how the varied social problems we are working to address are all connected to the CMP/Octo rather than as separate unrelated issues, we need to address the politics of ontological construction. In other words, how our concept of natural reality has been constructed and how the CMP/Octo plays out in daily life.

CP and the Flows of the CMP/Octo Across Settings and Time

The h*story of the United States indicates that we inherited certain worldviews started/created by English imperialism. Through the process of European colonization over-time grew the business model of the CMP/Octo. It is important to remember whose hands have shaped our current reality. The social constructions that dominate the structure of our current world came from the ideologies of a particular way of knowing and being in/with the world.

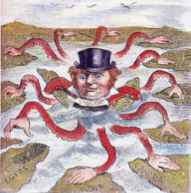

[https://www.alamy.com/stock-image-english-imperialism-octopus-162787570.html

We can imagine how the assumptions of the CMP/Octo flow through to the varied regions through the minds, hands, and decision-makers of the New World Order. Seymour Sarason, a community psychologist, quoted the need to critically analyze existing social, economic, technological, and organizational life. He articulated the importance of knowing the etiology through which settings are created in his book on “The Creation of Settings” (1972). He talked explicitly about how important it is to consider the historical developmental context through which social organization is accomplished and the importance of this for the creation of new settings. He discussed the importance of understanding the basic assumptions which govern thinking, and he critiqued ideas of “progress” marked by concepts of quantity and the passing of time. He states: “The Enlightenment is drawing to a dark close” (p. 5).

Sarason (1972) pointed out how history helps us to focus on the character of the thinking that created the system (not just the content of that system): “unless the compass that guides us has history built into it we will go in circles, feel lost, and conclude that the more things change the more they remain the same.” (p. 22). While the CMP/Octo is a psychological, sociological, and theoretical tool in understanding underlying ideologies embedded within our current moment, it should be noted that there is a long history prior to Euromodernity/coloniality. That history should also be accounted for if we are to understand the longer historical context out of which such a large system of control emerged (but is beyond the scope of this article).

We believe the flows/assumptions/narratives of the CMP/Octo shaping our ways of understanding reality (epistemic oppression) is a critical factor preventing our world from changing. If we consider that the assumptions of the CMP/Octo have been embedded in the worldviews, mindsets, and logics of the decision-makers since the inception of the United States as a nation-state, we should assume that all of our state institutions, affiliated non-profit, for-profit, and hybrid organizations, as well as dominant family/social-cultural systems, are also built with these onto-epistemological assumptions. This is akin to what has been articulated within the book “The Revolution will not be Funded: Beyond the Non-profit Industrial Complex” (INCITE!, 2007) and in Kivel (2016) referencing The Economic Pyramid (https://sfonline.barnard.edu/navigating-neoliberalism-in-the-academy-nonprofits-and-beyond/paul-kivel-social-service-or-social-change/0/).

The flows of the CMP/Octo have an invisible power embedded in language and discourse, and flow lie water through our institutional and organizational structures. One community psychologist that has written about the stability of organizational settings and their influence on human behavior is Barker (1968) on Behavior Settings. Through empirical research conducted during that time, he found there are a handful of organizational types that demonstrate certain behavioral patterns. He also found that, no matter who you placed into the roles within these settings, you would see similar types of behaviors. This research is consistent with more current literature on the stability of organizational culture (Cameron & Quinn, 2011). Given that the CMP/Octo is based on assumptions of control of and discrimination against certain social groups, and is embedded within organizational culture and structures that align with the CMP/Octo (i.e., policy, practices, social norms), we need a deeper analysis of how organizations participate in ongoing epistemic oppression, possibly as this overlaps with the work of another community psychologist, Rudolph Moos, assessing social context and climate (Holahan, 2002).

Federal and state institutions are responsible for a number of decisions made on behalf of large populations regarding health, education, and property. Significantly, these structures are shaped by disciplinary scholarship which adheres to certain philosophies of science. In some cases, these organizations are mandated to comply with policies they must only use “evidence-based research/practices.” This is problematic when the sciences on which those criteria were based on themselves use underlying principles and methodologies that marginalize certain onto-epistemological frames and treat people as objects (see Jimenez et al., in press; see also the science of eugenics in Yakushko, this special issue).

Ultimately, we need an embodied understanding of how our dominant understanding of reality and actions are tied, like puppets, to perpetuating the interests of the CMP/Octo. The institutions and organizations we work within are all part of this system of control. The ways they are funded by, and ruled/policed by, in many ways, need deep scrutiny. It is not accidental that they lack a breathing and feeling (beating) heart. To embody praxes of decoloniality within roles we hold is to be in constant critical analysis of these behavior settings, the narratives they perpetuate, and to act in ways that continue to dismantle harmful norms, or create completely new worlds.

Without a deeper understanding of how our thinking and behaviors are influenced by the CMP/Octo, we will continue to be the puppets of the CMP/Octo and likely fall back into old norms.

Our bodies will know and will tell us when something is not right. Transforming ourselves from being the puppet to cutting the strings, requires being attuned to new ways of knowing and being and seeing more clearly the assumptions that keep us in the experience of modernity/coloniality. Creating alternative settings (spaces) where we can learn this new way of knowing/ being, and practice exercising our voice and sense of empowerment to dismantle the norms, policies, and practices inherent in the design of settings built within the model of the CMP/Octo, are an important piece of this work (see Part 3 of this paper for more on space).

Education and Control of Subjectivities (Knowledge/Understanding)

Through “educational” institutions and systems (public schools, higher education institutions) the CMP/Octo reproduces its narratives through creating and re-creating subjectivities, funneling multiple generations of youth and adults through ongoing epistemic colonization[15]. Communities of color whose diasporas have originated within different worldviews and colonial histories live in the borders between this dominant socially constructed reality and alternative ones within which they grew up in at home, sometimes indicative by speaking more than one language (Rodriguez, 1982)[16].

The assumptions of the CMP/Octo above have been used as the foundation for justifying use of human and natural resources through academic study of the world through various disciplines such as community development, anthropology, and psychology for the development of the global economy. The natural and social sciences have been the primary industrial engine (the academy or canon) that controlled the ways we know the world via the development of concepts/constructs, and communication channels, including how we know social and natural life systems. The tools of “science” (in all of its set criteria) have constructed our world, and are perpetuated through text books, research methods, peer-review systems, academic mentoring, and reward systems.

Given the origins of the university as grounded in North and Central Europe and founded within religious belief systems of those regions, the assumptions of the sciences for understanding the world as objects has also been used to understand people as objects. This way of thinking and being allows for blatant exploitation of the natural elements of Mother Earth for purposes of the production of market goods and whole populations of people of color, specifically, to be used as the free labor behind the engine of the global economy. All these social constructions are important to serve the power and control of economy/capitalism. Therefore, we need to question/problematize the value of our systems of education and inquiry.

“The assumption that knowledge is based on a subject/object relation suddenly made the rest of the world an extended object of European knowledge. This was devastating for the dignity and humanness of people in the rest of the planet.” (Mignolo & Walsh, 2018, p. 200).

This article is intended as an intervention to stop the ongoing harm of the CMP/Octo.

Embodying decoloniality allows us to understand more deeply how grappling with and escaping the CMP/Octo is a necessary and at the same time an existential moment-to-moment and situational awareness. Through this increasing awareness of our ways of being in the world, we can see how the ways of modernity/coloniality are literally dripping from the walls and from inside our minds, shaping our subjectivities, roles, and common-sense ways of being.

This is a critique of psychology, community psychology in particular, in its current state. From an embodied perspective, our current paradigm of what constitutes “science” and “practice” is unable to help us understand the root of our problems. We are saying that our analysis of behavioral settings, community systems dynamics, political activism, program evaluation, and policy are incomplete and significantly misguided, at the very least. We need to re-examine the underlying ideologies that influence the shape, function, and power of institutions, organizations, and all behavioral settings designed within the framework of the dominant cultural paradigm of the CMP/Octo.

We need to change the sets of assumptions that make up our ontological and epistemological reality.

Community psychological work without this level of awareness contributes to ongoing praxes of disembodiment for people/beings at all levels of hierarchy. We must question what we are a part of, how our own disembodiment within daily settings and systems are manifesting these concepts at larger levels. Once we understand what to delink from, and our own power to do so, this is where we become radical. Embodiment is the next step.

…Grant us help then.

Help us to be more of the Earth each day!

Help us to be

more the sacred foam

more the swish of the wave!

From “This is Where We Live,” Pablo Neruda[17]

B. Embodiment as Praxes of Decoloniality

Engaging in embodied praxes of decoloniality is often a process of multi-dimensional shape-shifting. It emphasizes the interdependent individual and collective-level self-reflexivity needed to experience schematic tectonic shifts in how we perceive and connect with reality. It is a praxis of ontological-epistemological transformation toward a vision of a different world, which entails both letting go of one reality (set of horizons) and grabbing on to or creating another (See more information on the concept of the pluriverse in Escobar, 2020.) It is a form of remaking ourselves as “human” (Wynter, 2015). It is a process of learning to live differently within our bodies and with the world, reversing what has occurred over multiple generations and what is currently embedded in our social, political, and economic institutions.

Some of us who have experienced this kind of shape-shifting have referred to this experience as mini-earthquakes. Much like earthquakes, where plate tectonic activity is the hallmark of a planet undergoing changes at Earth’s core to adjust the elements of the global environment to make it more habitable, the tectonic activity we experience is the indication we are working on the deeper core of our being to make our environment more habitable as well. We believe this is the type of deep core shifts that occur within what is referred to as third-order change (Bartunek & Moch, 1987).

The analogy of an earthquake has been used to refer to deeper cultural change from cognitive and organizational sciences literature as well. Bartunek and Moch (1987) distinguish between first-order, second-order, and third-order change as they relate to organizational development. They refer to the importance of the concept of “schemata” in addressing how people gain deeper understanding of themselves and their organizational frames. Third-order change is “…to be aware of [our] present schemata and thereby more able to change these schemata as [we] see fit.” (p. 486). It refers to the development of the capacity for human systems to change our schemata as events require. Schemata have the potential to constrain or guide change, indicating that schematic awareness is important in realizing the underlying frameworks that shape the way we make sense of the world:

“cognitions, interpretations, or ways of understanding events are guided by organizing frameworks—or schemata . . . the portion of the perceptual cycle which is internal to the perceiver, modifiable by experience, and somehow specific to what is being perceived to alternative world views . . . we view schemata analogically as templates that, when pressed against experience, give it form and meaning. . .” (Bartunek & Moch, 1987; p. 484)

[Unknown Author [Online Image] (2022)]

Integrating embodiment and decoloniality together into a new schemata required to attend to the events we grapple with today has the potential to create deep level shifts in our worldview/senses. This frame integrates our cognitive schemas about reality (the CMP/Octo, modernity/coloniality) with deeper awareness of the emotional terrains experienced through sensations of our bodies, which widens what data is relevant to understanding the world. Integrating this data and interpreting these plates can manifest in tectonic shifts where the earth of our being shudders violently within us, causing damage to previous perceptions of the world and our place in it. Through this process we experience many emotions and realizations, including realizations about self, increasing awareness of the consequences of the way our current reality works, and our relationship to this.

To enact a decolonial and embodied way of being demands an increasingly deep understanding of how modernity/coloniality is embedded in our ideological lens, how it manifests within ourselves, collectively, together, with the world around us. It requires simultaneous engagements on multiple levels. This praxis presupposes understanding that we are submerged in modernity/coloniality under the guise of living out increasingly modern ways that produce devastating and irreparable harm to natural environments, other living beings, and ourselves (Mignolo & Walsh, 2018). Inevitably, this experiential process can bring feelings of loss and grief and is all part of the kind of internal composting we need to do to collectively reorient, and recreate our shared reality (i.e., compost-activism) (Akomolafe, 2016).

The embodiment of praxes of decoloniality encourages a larger framework in which our interpretations require deeper awareness and analysis of our experiences. Embodied awareness means that my body matters; the feelings and emotions I experience are part of my interpretations. This involves a multilayered process of delicately exploring current and h*storical trauma; mapping the complexes and symptoms that have arisen, and are continuing to arise from it, while seeing how these underlying ideologies have manifested across our shared reality. One major mythical tectonic plate to grapple with is the assumption of individualism. The bodies of others matter too. We are all connected. All of us are impacted—none of us are safe—we all create and recreate harm within this shared reality.

We embody praxes of decoloniality when our being has internalized a deep cellular-level awareness of the three interrelated concepts associated with decoloniality (i.e., the conceptual triad) and the feelings associated with participating in this reality. This awareness places us within cycles of reflection-action-resistance-delinking-creation—an integrated way of being where we understand the origins of the words that make the world, understand their impact, and become the active creator of new worlds/words. Gaining such awareness requires a reorientation of understanding grounded in bodily systems and the body’s interaction with the environment (Soylu, 2014), and this is what the authors in this special issue are doing in their narratives (See articles in this special issue by Samuel, West, Somerville, Palmer, Dieudonné).

Decoloniality needs to be felt in our body, so we can be in touch with the very personal ways in which modernity/coloniality manifest within ourselves and in relation to us. Feeling the realization of our participation in the production and reproduction of harm, whether to ourselves, to each other, or beyond humans, and connecting to that felt sense of responsibility is the key. There may be pain to be felt that has been numbed for some time, there may be healing to do around wounds that continue to be open, and there may be actions to take to ensure we speak up or step back, depending on our positionality to some event. This can be considered deep, honest work with ourselves through a personal narrative approach, or testimonios (de Jager et al., 2016).

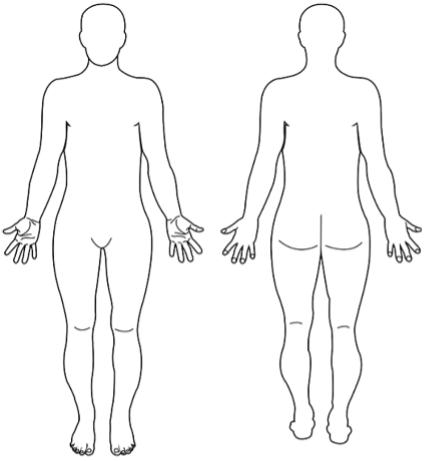

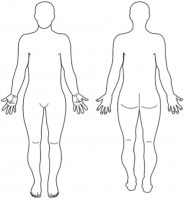

There are many ways we can go about these explorations, but one way to explore this is through body mapping, a strategy most commonly used in medical settings working to document and assess where physical harm is experienced within the body. In this case, however, harms can be physical, emotional, linguistic, spiritual, or any kind of experience where we may have numbed ourselves to the challenges of our existence and associated pains. In terms of health and health disparities, this undue and often unacknowledged package of harms associated with those of us experiencing varying depths of discrimination and exploitation, can tell us much about how to better our health through this telling of coloniality and ways modernity continues to oppress.

Questions to ask of our bodies might include:

We must constantly ask ourselves: how do we hold and participate in the production of ongoing harm, to other life forms and ourselves? Deep embodied awareness of these concepts resensitizes us to the subtleties of harm, the harms that have been normalized, that we participate in without realizing it.

This harm in which we participate in extends beyond our personal physical bodies, however, to include our intimate interconnectedness with each other in and across organizational settings, and integral natural ecologies all around us. Let us become more aware of this! For example, when we walk through a forest, we are walking with whole ecosystems of biodiversity, including tree roots, mycelium, mosses, plants, insects, etc., that all communicate and function together. When we have an awareness of such systems, and appreciate our own interdependence with them, the embodiment of this awareness encourages us to walk a little lighter and maybe also work to communicate with more nuance within this setting. This level of awareness of harm on an individual person-to-person level could make us even more aware of the harms we engage in when we speak (e.g., use of certain terms), the assumptions we make about how people perceive time, and how we respond to others (e.g., reacting with defensiveness instead of openness or curiosity).

We need to engage not just the content but the means, mechanisms, and epistemologies of oppression—not to relive our trauma but to understand the structures and systems that perpetrated them in a way that will enable us to change those systems and their roots. Changing not just the subject but the terms of the conversation requires letting go of the narratives, the constructions, and the epistemologies of modernity/coloniality. It requires knowing and learning what to let go of and what to grab on to.

Part Three: Space, Story-making, and the Village

A. Reclaiming Different Ways of Being

Non-modernity is a necessary concept and the starting point for reclaiming different ways of being.

How to access and navigate/sustain the experience of this “duality of existence”? Meaning, how do we live in two worlds at the same time?

The power of language is of critical importance to acknowledge. English betrays the Indigenous subject (Simpson, 2021) and others as well. Non-European knowledges and languages have been excluded and erased but nevertheless have survived.

“The bullet was the means of the physical subjugation. Language was the means of the spiritual subjugation,” Ngugi wrote. It also examined the close relationship between language and culture. For him “language carries, and culture carries, particularly through orature and literature, the entire body of values by which we come to perceive ourselves and our place in our world.” (Wa Ngugi, 2018, para. 2)

The genocide and catastrophe perpetuated by the CMP/Octo makes epistemic hegemony visible and sets the narratives and practices of “border” epistemologies as forms of resistance and re-existence. “To end coloniality is to end the fictions of modernity” (M. R. Trouilliot, as cited in Mignolo & Walsh, 2018, p.109) “Thinking without modernity, delinking from its fictions, is [a] major decolonial challenge. Decolonial knowledge production and critique are part of an entirely different paradigm of being, acting, and knowing in the [colonial] world” (Maldonado-Torres, 2016, p. 7).

Modernity and all of its fictions and premises are the faces of the CMP/Octo.

You cannot decolonize knowledge if you do not question the very foundations of Western epistemology and ontology, (i.e., Kupe vs. Cook).[18] As long as questions (“scientific” inquiry) remain within the rules and horizons of the existing naming game, the world of the CMP/Octo (Modernity), the dominant ideologies currently shaping the worlds of the APA and SCRA, the control of knowledge itself is never called into question.

First people’s and Indigenous knowledge have been defined as a “multidimensional body of lived experiences that informs and sustains people who make their homes in a local area and always takes into account the current socio-political colonial power dimensions of the Western world” (Grayshield, 2010, p. 6). Many Indigenous/tribal cultures related “harmoniously to their environment, experienced colonization, and provided an alternative perspective on human experience that differed from Western empirical science” (Denzin et al., 2008, as cited in Grayshield, 2010).

(Re)learning Indigenous stories, myths, ways of seeing and knowing, can be one framework to understand the ways coloniality has broken, paralyzed, and disconnected us from our bodies and the natural world. For many of us that have familial lineage tying us to Indigenous ancestry or cultural worldviews/practices that have been buried or forgotten over time, we may lean in to reconstruct them, ourselves, in a process of revisioning and remaking a relational (disalienated) and embodied self and community. However, we know that connecting with Indigenous knowledge systems is one of many ways we can learn to embody praxes of decoloniality. We each need to find our own way. As Gloria Anzaldúa (2015) explained: “I need a different mode of telling stories, one that can simultaneously hold the different models of what I think reality is. I need a different way of organizing reality.” (p. 43).

Embodying decoloniality consists of unlearning normalized reality, of seeing through reality’s roles and descriptions, [Diagram Description automatically generated] contesting and disrupting narratives and constructions, by acts of non-doing and non-being (Anzaldúa, 2015). Dissonance, depression, dispossession, expressions and manifestations of resistance and re-existence are forms of unconscious separation, of letting go. These manifestations need to be reframed, “externalized.” Where does this exist in social/political/economic spheres? When we feel disoriented or depressed, we need to understand this, not necessarily as a harm to push away or to numb (avoid) through medication or other means, but as possibly evidence of an unconscious desire to delink and a desire to connect to another self. Within the context of coloniality, other epistemologies take on greater meaning, particularly in regard to experiences of the body and psyche/spirit, because these could be aspects of ourselves that are silenced within the frame of coloniality. This allows for the creation-emergence of a new reality based on different premises and values.

In these new spaces, the Who-We-Are experiences disintegration and reconstruction. It allows the creation of different narratives based on the identification of shared or parallel experiences while honoring the particularities of each individual’s or community’s lived story. It facilitates the exploration of the ramifications of what we’re becoming and the confrontation with the shadows of our times. It opens the possibility of the emergence of a consciousness that transcends the “us” vs. “them,” bridges the extremes of coloniality’s binaries, and holds a subjectivity and a space that does not polarize.

“A process of emotional psychical dismemberment, the splitting of the mind/body/spirit/soul, and the creative work of putting all the pieces together in new form, a partly unconscious work done in the night by the light of the moon, a labor of re-visioning and re-membering.” (Anzaldúa, 2015, p. xxi)

In my own process of learning to embody praxes of decoloniality and reclaiming new ways of being, I (Tiffeny) needed to visually map memories of the various ways I experienced forms of harm from epistemic oppression over time (harm to me and harm I have caused/participated in). Seeing my body on a page and recalling messages received, or the development of assumptions that became embedded in my interiority, helped me to recall various forms of harm. I simply had masked, hidden, forgotten, or misplaced my connection to self/body—a deep loss regarding wisdoms embedded in experiences of dis-ease, dis-function, dis-connection, dis-possession, and dis-association. I realized how much of what I had come to know as normal ways of being were coping strategies I had learned to use to survive in settings that were designed to control or limit authentic self, self-expression, self-determination, and feelings of self-efficacy. This occurred in many places across my lifespan where I would have expected to be supported otherwise. This is how pedagogy for the oppressed works—pedagogy in terms of what we are taught, what we are taught to dim, and how we are taught to relinquish aspects of ourselves, our anatomy, to institutions. As someone who is comprised of multiple mixed identities—Indigenous Americas-Mexican, Irish, Portuguese, Scottish, Spanish, and Northern European familial lineages—and who is quite unsure how I am perceived by others, yet primarily speak English, appear as female, and am queer, identity, belonging, and feeling a sense of community in the United States is a challenge. Especially when living in unfamiliar places where identity is primarily tied with race/ethnicity and class, which gets even more complicated when queer. This is also what many of us call living in the borderlands—a constant process of knowing the world in more ways than one and negotiating awareness of such experiential data in ways that allow us to survive or thrive despite the impact such navigation of rocky terrain may have on our health. Epistemic oppression is embedded; deeply and psychologically. To reclaim new ways of being through embodying praxes of decoloniality is to learn to live beyond the hegemony.

Focusing too long on our identities (as constructions) separates us, as our existing social and political environment requires of us. Without some sort of guide or path to grab onto, we can get bogged down in identities as they are understood through modernity/coloniality. The work of increasing awareness of our own narratives and how we are shaped by the CMP is helpful for identifying how we are being harmed and doing harm by believing and enacting these dominant ideological threads. It doesn’t matter what the identity is based on—race, sexuality, gender, age, ability, class or some other categorization used against us—they are all part of a system of control.

Therefore, we cannot address problems of the social/political world without addressing our own healing/transformation and participation in perpetuating ongoing harm (i.e., “post-activism”[19]). Through the acknowledgment of the workings of the CMP/Octo, and how the flow of narratives about ourselves perpetuate historical/multigenerational trauma, we learn the power to rename, reclaim, and re-exist. Through this re-creation of the world we become sovereign (self-empowered; see self-activism, Gloria West, in this issue).

“So, don’t give me your tenets and your laws. Don’t give me your lukewarm gods. What I want is an accounting with all three cultures—white, Mexican, Indian. I want the freedom to carve and chisel my own face, to staunch the bleeding with ashes, to fashion my own gods out of my entrails. And if going home is denied me then I will have to stand and claim my space, making a new culture—una cultura mestiza—with my own lumber, my own bricks and mortar and my own feminist architecture.” (Anzaldúa, 2010, p. 6–7)

B. The Village as a Praxis of Reclaiming

An example of a project of this type (what became known as the Village) began in the summer of 2017. We[20] had just completed a second racial justice and psychology conference. The conferences had been a radical departure from the past, not just because the content was focused on racial justice. The organizers had asked two questions:

Both conferences were part of an initiative to place racial justice and communities of color at the center of psychology. To do so the space was shifted from hierarchical to relational, academic to community-centered. After the closing, questions that emerged included: How do we forge ahead as a group and conference? Where is the destination, and will it find home?

We began to envision a writing project that included collaborative writing circles that would work together over a longer period of time. The intention was to move beyond presentation and dialogue and towards collaborative investigations (re-search) and articulation (writing) of how a de-colonial framework could shift psychology’s perspectives.

Why decoloniality? Equality within a system of oppression is not the goal; neither is moving to a different position within the hierarchies. Decoloniality moves us beyond modernity (outside the box), beyond justice, beyond race. It allows us to see race as a form of social control (see Palmer, G. in this issue) and as part of a colonial matrix of power (CMP/Octo). Racism does not exist only as a form of oppression of one racialized group by another, but more significantly as part of a web (system) of control over all communities/continents/worlds.

At one of the initial planning sessions, we sat together in small groups sharing stories. Someone started talking about villages in Chicago, referring to their experience of growing up in public housing projects. How it was, at one time, a self-contained and self-supporting community. How it changed, how gangs and drugs impacted and divided the village. People remembered different things, different stories, and different parts of the stories. At the same time, they couldn’t say, they couldn’t describe exactly what happened to those villages. Yet people remembered something, and those memories were very deep and charged with emotion. What they remembered and processed over the last three years is the subject of this section.

C. Space as a Condition of Embodiment

Sacred (non-commodified and non-objectified) space is a condition for re-membering, healing, and intentionally re-existing. It provides a validating mirror to reclaim deep layers of experience which have been erased and normalized. Re-membering in a colonially occupied (defined) space often triggers a re-experiencing of trauma.

In these occupied spaces we are required to disconnect from our lived experience to comply to what is expected of us, (i.e., how we connect with others, how we sense what’s needed, how we express ourselves, etc.). This leads us into the borderlands, the in-between spaces, the cracks where we are torn between two or more different scripts (narratives) of behavior, mannerism, tone, language, and role. We often experience uncertainty, instability, anxiety, depression, and conflicting identities. Some adapt and navigate by code-switching, developing multi-modal capacities. However, the overall effect is that we exist as disembodied and dissociated from ourselves, our communities, and the world.

****

Being aware of the mechanisms that shape our understanding of the world [and ourselves] is a precondition to a process of liberation from current ways of being, of going beyond prescribed understandings and constructions of reality. (Andreotti & Dowling, 2004; Martín-Baró, 1994)

****

Remembering in a non-occupied space helps one remember What/Who-We-Are outside of the categories ascribed to us by modernity. To re-witness the violence of disembodiment in a way that begins to reframe the context of one’s trauma-oppression.[21] Different feelings, reflections, and stories of the trauma emerge within the context of the witnessing. Who-you-are changes – a different you becomes more visible and real.[22] Re-membering without reliving. It has been described as a “stance of opposition [and affirmation] which creates a liberated territory” (Morales, 1998; p. 62).

Holding this kind of space requires presence, authenticity, and relationality. It is a process of letting go and reaccessing , being fully present in relationship with self and community, “full speech,”[23] deep listening, and re-languaging.[24]

From the point of view of the CMP/Octo this space may appear as one of non-doing. It appears unstructured, disorganized, and unproductive. To enter it requires detachment from the CMP/Octo’s flows/way of being/thinking/relating. To exit the space requires a conscious return. The space is attentive to and affirmative of the body and psyche, to non-articulated experiences of self and selfhood, to ancestors, food, home, non-colonial languages – to conflicted emotions and psychological splitting that surface as a result of living in two worlds (Anzaldúa, 2015; Somerville, this issue).

People come into unoccupied space already in conflict (disembodied)—torn within social constructions; outside its narratives and inside its fractures. As participants in these spaces, we remind ourselves to be fluid and compassionate in holding the space as each of us grapples with these shifts, contradictions, and re-orientations. To hold these conflicts and tensions requires a capacity to prioritize reflection and discernment, and to reframe how “productivity and achievement”[25] are defined (N. Nasrat, personal communication, November 7, 2021). That time is fluid, not fixed, that transformation and healing are circular, not linear. That it is important to slow down, to allow for and acknowledge what is held in silences, to listen for and to follow different rhythms and processes. To resist and let go of colonial patterns and modalities.

This space is what nurtures our stories and gives life to our silenced selves and communities. Without it shifting we continue to live in the crevices and reproduce the constructions and fault lines in which our bodies and psyches have been embedded and encaged in over multiple generations. Without it, we cannot make our way to the village.

There is intention and permission to detach from the CMP/Octo, to not follow the norms and expectations of coloniality (standard operating procedures). There is an understanding that it will be challenging, discomforting. At the same time, one experiences it as liberating. As one of the members of the village said,

“You can feel this when you’re in a decolonial space – less so in colonial spaces: These [stories] . . . came from a moment of decolonialitizing space with my fellow authors. It was a rich and inspiring discourse that felt like an intellectual pilgrimage as we were discovering our truth.” - Jacqueline Samuel, (personal communication, August, 23, 2021)

In this space, embodiment is recognized and validated. There is an intention to reconnect our silenced thoughts and feelings to our consciousness. To acknowledge and engage emotions as a necessary part of the practice. That uncertainty is part of the process. That not knowing is a form of contesting epistemic colonization; that not knowing can be more important than knowing.

D. The Story and the Village

Out of the space emerges the story.

The story is a canoe, a vessel, and a vehicle that is the container for the life of the subject.[26]

A vessel that has taken the subject and their community on its journey, that is, the lived experience of the person as part of a people.[27]

The stories are ones of political, educational, and economic trauma, racial oppression, somatic conformity (body shaming, disability discrimination), and others, intertwined with resistance and memories of previous identities, roles, traditions, and practices. The subject is the content of the story. The subject is the story. Not learning about the subject, learning from the subject. The subject is the embodiment and affirmation of that experience and of that knowledge.

“Our lives are the textbooks and it is our way to liberate the minds of the people” (Adriano, 2012, p. 64).

The story is the journey of the subject over multiple generations. The subject is the author of the story. Not seen or interpreted by someone else (scholar or expert) but by each person, themselves, in a space with other members of the village. From the perspective of healing and empowerment, the subject must be the “author and arbiter of her own recovery . . . No intervention that takes power away from the survivor can possibly foster her recovery, no matter how much it appears to be in her immediate best interest.” (Morales, 1998, p. 63; quoting Judith Herman).

The story is like a map to the village.

To locate and find the village requires understanding how it was and is being destroyed. Villages are identified based on the existence of relationships, a system, political, economic, psychological, and spiritual, that supports the individual and the community. Villages are weakened and unable to function when that system has been disconnected and disabled.

The destruction of the village was not accidental. It was a consequence of “conquest” and the imposition of a different way of being (i.e., the CMP/Octo). The violence was and is still normalized. Its way of life was replaced by a Eurocentric society. Civilization and its particular ways of life have been presented as superior and de facto, that civilized world has viewed people of the village as objects to be measured, categorized, named, pathologized and used.

Coloniality impacts the village and its people internally (i.e. psychologically, politically and economically). As a result, the colonized subject is at war with themselves, trying to kill any trace of the black, native, and colonized within and without, while also being at war with each other to achieve the same purpose (Maldonado-Torres, 2016, p. 14). Malcolm X (1962) asked: who taught you to hate yourself?[28]

Jacqueline Samuel explains,

This is not to say that African American’s don’t trust each other. It is really to say that self-hatred has a grave impact on our community. It impacts how we vote, spend, live, work, worship, and educate ourselves. As it happened on the plantation, it is still happening today. What is disturbing is self-hatred stops our ability to thrive and this behavior starts at an early age when it can be prevented. Unfortunately when you see so much conflict and violence in the community you know that those individuals that engage in disruptive behavior are void of the nurturing from the Village where they need that connection to grow. - Jacqueline Samuel, (personal communication, August, 23, 2021)

The destruction of the village and the phenomena of self-hatred are connected. Self-hatred is both a consequence of the CMP/Octo and a barrier to seeing how it causes our destruction. That is, coloniality in the form of self-hatred blinds one to their trauma and simultaneously prevents them from connecting with the village.

Despite, and in the face of, this multi-generational catastrophe, the village has survived. Memories of it exist and are passed on in ways that we are not fully aware of.

They exist in our stories.

Deidra Somerville describes the role of the mother in the life of the village.

The stories of who we are, who we were and who we are to become are derived from what has been mapped onto the wombs, hearts, minds, and spirits of the identities of our mothers. The condition of our very humanity, both the process of becoming more human, and the actions that define humanity, arise from our notions of motherhood, experiences with our mothers, and retelling of our mother’s stories. For their stories tell ours. (Somerville, this issue)

Gloria West describes it as:

I choose not to be overwhelmed. To work in the world but not be sucked into it. To identify and re-draw the boundaries and to know that one is enough. To stand up for yourself because you’re the only one who can. To learn self-love as part of a self-activism that is in relationship with community and even those from outside of your community. (West, this issue)

The motherline and self-activism allow us to re-conceptualize and build the village as a viable project.

E. (Un)mapping the Colonial Matrix of Power

There are different kinds of “stories.” The stories of the perpetrators are normalized, legitimized, incorporated into the collective narrative (i.e., dominant flows of the CMP/Octo). It is the world that exists, that people live and are forced to survive in. The stories of the abused, the oppressed, are erased, silenced, and retold through the framework and language of this society’s “reality.”

The keys here are that:

[To] identify and clarify the various layers, moments, and areas involved in the production of coloniality as well as in the consistent opposition to it. The goal is to better understand the nexus of knowledge, power, and being that sustain an endless war on specific bodies, cultures, knowledges, nature, and peoples… (Maldonado-Torres, 2016)

The journey to the village turns out to be part of a larger project to map the colonial and capitalist matrix of power, to critically question and reveal the interconnections of how it functions, to make it visible and to understand its evolution over time. This includes mapping the psychological complexes and symptoms of communities and individuals that have arisen and continue to arise from it. Empowerment from a community psychological perspective cannot exist in isolation from this framework.

Empowerment in this context is the ability to negotiate one’s own subjectivity and to go beyond imposed boundaries.

The stories and their embodied experience that contain memories of the CMP/Octo also contain memories of the Village. The individual, present and past,[30] is a microcosm of the village as well as the CMP/Octo. Within the same crevices and fractures that disembodied us lie memories of what and Who-We-Are before and during that disembodiment. It requires a practice of putting ourselves back together, re-membering.

The stories in this issue create a different reality. They ground us outside modernity. They help us see ourselves and the world differently.

“There’s something epistemological about storytelling. It’s the way we know each other, the way we know ourselves. The way we know the world. It’s also the way we don’t know; the way the world is kept from us, the way we’re kept from knowledge about ourselves, the way we’re kept from understanding other people.” (Anzaldúa, 2015; citing Andrea Barrett, p.1, Preface)

When the stories of the village emerge, they “dissolve” the constructions of the CMP/Octo. Something new is remembered, named. We can breathe. One experiences a sense of being a different person, the world a different place. It makes possible and is a foundation for a new culture of politics. This is a decolonial praxis of embodiment.

Closing

To repeat – this article is intended as an intervention to stop the ongoing harm of the CMP/Octo.

Let us be honest with ourselves – all of us – that the current configuration of life itself is not how we want to be.

While re-membering our stories and roots may be important for attending to deeper understanding of who we are, we will need to bring a critical lens to those ways of being as well. Hierarchical structures emerged among civilizations thousands of years before us. Why was this necessary? Let us be part of a world that allows for pluriversality while also not replicating dynamics of power over others, or complete disregard for the worldviews of others.

We hope that we learn to develop more creative paths forward, together, while also acknowledging our own individual stories. To create a world where these colonial concepts no longer hold power. From a long-view perspective, ideally, everyone learning to hold multiple worldviews simultaneously, without conceding that one worldview is more valid than another is, is of paramount importance.

Learnings from the Village

The village is a necessary alternative space for incubating/creating new worlds – a space for learning to embody praxes of decoloniality – empowered within a new kind of politics. It is a space of story-making and storytelling. We construct and apply a framework that does not and cannot exist within the “logics” of coloniality. Engaging our entire bodies, the space holds a fabric that affirms and legitimizes different possibilities for selves outside of prescribed constructions. It is a place where a different way of knowing and being becomes real.

We suggest the following were key aspects of the village as an embodied decolonial praxis in the United States:

We suggest the following as principles and precepts of embodying decoloniality:

We close this article by inviting you to consider this as the challenge to and the calling of community psychology. The ways of embodying decoloniality and the ways we enacted the village space are not meant as a model to be replicated as is. The point is to support the ways of the Rhizome (Deleuze & Guattari, 1987). Rhizomatic developments of these ideas would ideally look different in different places, with the unique perspectives, h*stories, and positionalities of those engaging in their own worldsenses. We hope to learn more about the creative ways embodying decoloniality happens around the globe. We look forward to hearing your comments and questions and hope that there will be spaces where we can engage in more in-depth dialogue and discussion.

An other world is here.

NOTES

[1] Author's Note

[2] “It was an exciting time . . . [Swampscott conference participants] wanted to intervene in social problems that were not explicitly mental health in nature, and that’s why they talked about becoming “social change agents” – a vision that was a sea change for American psychology” (Tebes & Simons-Rudolph, 2016, para. 1).

[3] “ABPsi was formed in the wake of the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King and the rise of Black Nationalism of that era. ABPsi intended to create a psychology of the Black experience focused on improving the circumstances of Black people. Their initial purpose was to help Black psychologists in a time of discrimination and to provide psychological resources to the larger Black community. The founding psychologists believed that a psychology created mostly by white middle-class men could not explain the situation of people of African descent, and moved to incorporate African philosophy and cultural experience into the creation of a new understanding of Black psychology. The principles of ABPsi’ s creation were “to organize their skills and abilities to influence necessary change, and to address themselves to significant social problems affecting the Black community and other segments of the population whose needs society has not fulfilled.” The founders actively chose to remain independent of the American Psychological Association, decrying that body's complicit role in perpetuating White racism in society and the prevalence of studies featuring only White male participants. Instead, the ABPsi took a more active stance, seeking “to develop a nationwide structure for pooling their resources in meeting the challenge of racism and poverty” according to a statement released at their founding in 1968. Ebony Magazine's publication of "Toward a Black Psychology" by Joseph White in 1970 was a landmark in setting the tone and direction of the emerging field of Black Psychology” (Wikipedia, n.d.b)

[4] “The Radical Therapist was a journal that emerged in the early 1970s in the context of the counter-culture and the radical U.S. antiwar movement. It was an "alternate journal" in the mental health field that published 12 issues between 1970 and 1972, and "voiced pointed criticisms of psychiatrists during this period". It was run by a group of psychiatrists and activists who believed that mental illness was best treated by social change, not behaviour modification. Their motto was "Therapy means social, political and personal change, not adjustment".[2] Why have we begun another journal? No other publication meets the need we feel exists: to unite all people concerned with the radical analysis of therapy in this society. It is time we grouped together and made common cause. We need to exchange experience and ideas, and join others working toward change. The other “professional” journals are essentially establishment organs which back the status quo on most controversial issues… We need a new forum for our views. In the midst of a society tormented by war, racism, and social turmoil, therapy goes on with business as usual. In fact, therapists often look suspiciously at social change and label as ‘disturbed’ those who press towards it. Therapy today has become a commodity, a means of social control. We reject such an approach to people`s distress. We reject the pleasant careers with which the system rewards its adherents. The social system must change, and we will be workers toward such change” (Wikipedia, n.d.e)

[5] “Frantz Omar Fanon, also known as Ibrahim Frantz Fanon, was a French West Indian psychiatrist and political philosopher from the French colony of Martinique. His works have become influential in the fields of post-colonial studies, critical theory and Marxism. As well as being an intellectual, Fanon was a political radical, Pan-Africanist, and Marxist humanist concerned with the psychopathology of colonization and the human, social, and cultural consequences of decolonization. In the course of his work as a physician and psychiatrist, Fanon supported the Algeria's War of independence from France and was a member of the Algerian National Liberation Front. For more than five decades, the life and works of Frantz Fanon have inspired national-liberation movements and other radical political organizations in Palestine, Sri Lanka, South Africa, and the United States. He formulated a model for community psychology, believing that many mental-health patients would do better if they were integrated into their family and community instead of being treated with institutionalized care” (Wikipedia, n.d.d).

[6] “Césaire's ‘Discourse on Colonialism’ challenges the narrative of the colonizer and the colonized. This text criticizes the hypocrisy of justifying colonization with the equation ‘Christianity=civilized, paganism=savagery’ comparing white colonizers to ‘savages.’ Césaire writes that ‘no one colonizes innocently, that no one colonizes with impunity either’ concluding that ‘a nation which colonizes, that a civilization which justifies colonization - and therefore force—is already a sick civilization.’ He condemns the colonizers, saying that though the men may not be inherently bad, the practice of colonization ruins them. He also examines the effects colonialism has on the colonized, stating that ‘colonization = “thing-ification'", where because the colonizers are able to ‘other’ the colonized, they can justify the means by which they colonize” (Wikipedia, n.d.a)

[7] Carter Godwin Woodson (December 19, 1875 – April 3, 1950) was an American historian, author, journalist, and the founder of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History. He was one of the first scholars to study the history of the African diaspora, including African-American history. Carter G. Woodson was born in New Canton, Virginia on December 19, 1875, the son of former slaves, Anne Eliza (Riddle) and James Henry Woodson. His parents were both illiterate and his father, who had helped the Union soldiers during the Civil War, supported the family as a carpenter and farmer. The Woodson family were extremely poor, but proud as both his parents told him that it was the happiest day of their lives when they became free. Convinced that the role of his own people in American history and in the history of other cultures was being ignored or misrepresented among scholars, Woodson realized the need for research into the neglected past of African Americans. Along with William D. Hartgrove, George Cleveland Hall, Alexander L. Jackson, and James E. Stamps, he founded the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History on September 9, 1915, in Chicago. Woodson described the purpose of the ASNLH as the "scientific study" of the "neglected aspects of Negro life and history" by training a new generation of blacks in historical research and methodology. Believing that history belonged to everybody, not just the historians, Woodson sought to engage black civic leaders, high school teachers, clergymen, women's groups and fraternal associations in his project to improve the understanding of Afro-American history” (Wikipedia, n.d.c).

[8] William Edward Burghardt Du Bois (February 23, 1868 – August 27, 1963) was an American sociologist, socialist, historian, civil rights activist, Pan-Africanist, author, writer and editor. Born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, Du Bois was one of the founders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1909. Racism was the main target of Du Bois's polemics, and he strongly protested against lynching, Jim Crow laws, and discrimination in education and employment. His cause included people of color everywhere, particularly Africans and Asians in colonies. He was a proponent of Pan-Africanism and helped organize several Pan-African Congresses to fight for the independence of African colonies from European powers” (Wikipedia, n.d.f).

[9] The film, the Truman Show, is a good illustration of the principle of horizons. See also Constructing the Self, Constructing America (Cushman, 1995).

[10] The film, The Matrix, provides one depiction of what how our experience and perspective on the world can shift through increased consciousness of the structures embedded within these ideologies and what it means to “delink”.

[11] See a recent interview with Walter Mignolo here: https://www.e-ir.info/2017/01/21/interview-walter-mignolopart-2-key-concepts/?fbclid=IwAR0gyRhaOBAkwT2kcEaeqnxREYuftssWYmT_F83JQQQLpwUJdb9RAWLuBcY

[12] This includes: racial justice, environmental justice, disability justice, epistemological justice, sociolinguistic justice…etc.

[13] At a mtg. in May, 2018, there was a discussion about oppression, trauma, and what it feels like. There was a sense that it was bigger than just what was in front of one, that it had multiple arms - that it sometimes hit one from not just the front, but from the sides and the back, where one couldn’t see it. Someone said “it feels like an octopus!” Then, someone went up to the board and drew an Octopus. When we saw the picture, everyone went “oh yes!” It resonated at a deeper level. There was a collective sense that we had named “something.” It was “just a feeling.” However, it turned out that this feeling led us towards what has become a central image of a 3-4 year project, and an image that has been used by others beyond our Village to explain similar phenomena. You will find an image of this conceptual octopus as it manifested on a whiteboard in Part 3 of this paper. (See: https://coco-net.org/white-supremacy-culture-in-organizations/

[14] Another term used to reference the CMP/Octo. To quote my sister, Anasuya Isaacs, from our “We Will Dance with Mountains” course: “We live in the Patrix disguised as a matrix holding up misogyny sneakily.”

[15] The cultural injustice that occurs when the concepts and categories by which people understand themselves and their world are replaced or adversely affected by the concepts and categories of the colonizer.

[16] This autobiography by Mexican-American writer, Richard Rodriguez, called “Hunger of Memory: The Education of Richard Rodriguez” tells his story of cultural loss through language and education. He tells us: Once upon a time, I was a ‘socially disadvantaged’ child. An enchantedly happy child. Mine was a childhood of intense family closeness. And extreme public alienation. Thirty years later I write this book as a middle-class American man. Assimilated… It is education that has altered my life.”

[17] For more information on the Chilean poet, Pablo Neruda: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/pablo-neruda

[18] Maori communities and Indigenous scholars in New Zealand have framed it this way. Kupe is a Maori ancestor who knew the world through his own traditions and ways of knowing (epistemologies). James Cook, the English colonizer, knew the world through the European “sciences.” These two epistemological systems lead to two very different ways of being. The assertion of hegemony of one over the other was and is part of the project of coloniality. The reclamation and practice of their non-European epistemology is part of their vision for the present and the future.

[19] The concept of “post-activism” was coined by Bayo Akomolafe as “a new form of deinstitutionalized activism, if you will – represents a leap into the dark…embracing the unknown.” See: https://www.bayoakomolafe.net/post/the-times-are-urgent-lets-slow-down

[20] The Racial Justice Action Group and the Racial Justice in Praxis project; projects developed in 2016-18 as part of PsySR (Psychologists for Social Responsibility), a national group formed in the early 1980s.

[21] “I am traumatized. I am oppressed. I am not responsible for nor was I the cause of my trauma. What happened to me, my ancestors, and my community(s) occurred and continues to occur in the context of a larger story.” The trauma is not Who-You-Are; the trauma is what happened to you (M. James, personal communication, July 21, 2021)

[22] The world of you (Maldonado-Torres, 2016).