This paper will chronicle the racial justice praxis the authors, and seven additional white colleagues, have undertaken in response to our growing awareness of the need for critical-liberatory spaces in which white anti-racist cultures can be cultivated. The practices undertaken by the group of white therapists and psychologists are a gesture toward anti-racist imaginings; striving to disrupt social and institutionalized white body supremacy. This work is informed by the recognition of a longstanding call from Black and Indigenous People of Color (BIPOC) for white people to recognize that dismantling white supremacy is white peoples’ work. Our practices draw on long lineages of Black radical imaginations and BIPOC theory, including works from Octavia Butler, Grace Lee Boggs, Derrick Bell, Robin D.G. Kelly, N.K. Jemisin, Dr. Joy DeGruy, adrienne maree brown, and many other BIPOC thinkers and cultural world-builders.

Please click here for the PDF version of this article.

“There is nothing new under the sun, but there are new suns.”

~ Octavia E. Butler

Introduction

This paper will chronicle the racial justice praxis the authors, and seven additional white colleagues, have undertaken in response to our growing awareness of the need for critical-liberatory spaces in which white anti-racist cultures can be cultivated. The practices undertaken by the group of white therapists and psychologists are a gesture toward anti-racist imaginings; striving to disrupt social and institutionalized white body supremacy. Our group has adopted the concept of ‘imaginings’ to ensure that our praxis embodies the spirit of curiosity and dialogue without the pressure to ‘arrive’ at conclusions. This work is informed by the recognition of a longstanding call from Black and Indigenous People of Color (BIPOC) for white people to recognize that dismantling white supremacy is white peoples’ work. Our practices draw on long lineages of Black radical imaginations and BIPOC theory, including works from Octavia Butler, Grace Lee Boggs, Derrick Bell, Robin D.G. Kelly, N.K. Jemisin, Dr. Joy DeGruy, Adrienne Maree Brown, and many other BIPOC thinkers and cultural world-builders.

Through such work we hope to participate alongside the traditions of critical, liberation, feminist and post-colonial psychologies (Burton, M. & Kagan, C., 2014; Fox, D. & Prilleltensky, I. (Eds.), 1997; Fox, D., Prilleltensky, I. & Austin, S. (Eds.), 2011; Lykes, M. B., & Mallona, A., 2008; Martín-Baró, I., 1985; Moane, G., 2010). The group aims to shift away from a white culture-normed, individualized, dis-embodied, medical-model of psychology. Our work joins that of other critical psychologies in the hope of establishing robust anti-racist and liberatory models of repair, reconciliation, and reparation (Coates, 2014; Menakem, 2017; Nieto, 2010; Kendi 2019; et al.).

The article will outline the history of our groups’ formation and offer an analysis of the scholarship and activism that has informed our approach. We will provide examples of our imagination practices, explore the successes and challenges of our work together and reflect on future hopes for our work and the potential contributions it may present to the field of critical community psychology practice.

To begin, we see our work as a part of several praxis-oriented traditions. Our discussions of group work and vision are informed by Critical Community Psychology (Kagan, C., Burton, M., Duckett, P., Lawthom, R., Siddique, A., 2011), liberation and feminist psychologies (Lykes & Moane, 2009), as well as somatic, or nervous system-based, trauma theory (Levine, P. A., 1997; Menakem, R., 2017; Porges, S.W., 2011; Van der Kolk, B. A., 2014, Ogden, P., 2015). We also draw from anti-racist movements and inquiry lineages from outside academia. These include grassroots anti-fascist and anti-capitalist theory and practices, coalition-based social movement work and abolitionist traditions[1]. Our group has utilized the notion of movement lineages, akin to Martin-Baro’s (1986) emphasis on the recovery of historical memory, to identify the intellectual and activist legacies we bring to our work. We emphasize curiosity for the movement lineages each group member brings to our relational work, and in particular, those lineages outside formal academia.

As Watkins and Shulman (2008) state, we endeavor to be an example “...where individuals and communities have found local, creative, and participatory solutions to problematic conditions and institutions by transforming their psychological relationship to self and other, sometimes in dialogue with psychologists who are transgressing academic boundaries” (p.16). It is the authors’ hope that by sharing some of our groups’ experience, as therapists and psychologists specifically, we will add to the body of critical community psychology practice. We hope this paper reads as a case study outlining the dynamics of a group constructed by white mental health professionals to build anti-racist culture within our contextual environment. In this paper, we aim to closely describe our groups’ formation, process, ruptures and repairs over the last two years.

History

In the Fall of 2018, a multi-racial group of mental health therapists and psychologists began organizing and fundraising to bring nationally recognized racialized somatic trauma expert, Resmaa Menakem, to Seattle, Washington, for a weekend event. The gathering was inspired after several Seattle-area therapists and psychologists read Menakem’s book, My Grandmother’s Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending our Hearts and Bodies (2017). Group members met monthly for one year, focusing on event planning with an implicit intent to create what Menakem calls a ‘cultural container’ in the planning process. Cultural container is a term utilized by Resmaa Menakem (2017). This term speaks to the intentional process whereby members of a group commit to long-term engagement in practices and relationships that become the building blocks for culture. In this instance, the deliberate work of creating a white, anti-racist striving culture that can ‘contain’ the ruptures and repairs necessary for building somatic fortitude (or stamina) in white bodies. This container includes cross-racial relationship-building, and community networking.

Event planning prioritized centering Black and Indigenous People of Color (BIPOC) in both the process and execution of the weekend itself. The group worked with Menakem’s team to ground these anti-racist values in his call for embodied container work. Another explicit goal was to develop more racial stamina[2] and capacity to address the ruptures and wounding that inevitably occur in cross-racial (and white-caucus) organizing. Despite members of our group being long time anti-racist activists, this kind of container-building was novel.

The initial year of mixed racial organizing included anti-racist relationship-building and somatic practices with a focus on interrupting white-normed methods in both the planning and the weekend itself. This resulted in several steps towards de-centering whiteness: a BIPOC-only Friday night event with Resmaa Menakem, pre-open-registration ticket sales for BIPOC-only with a sliding scale, a community reparations fund where community members could pool money for BIPOC registration, a BIPOC healing space at the event, and a higher than average percentage of People of Color, and Black participants in particular at the event (atypical for Psychology-based events in Seattle, Washington).

We also faced challenges and confronted ways our implicit and explicit anti-racist intentions did not manifest. For instance, we had People of Color but no Black members in the planning group, which we recognized as the anti-blackness baked into anti-racist work, even in multiracial anti-racist organizing. We also noted the deeply segregated legacy in our therapy community, which despite the higher-than-average number of BIPOC attendees, remained largely, and sometimes painfully, intact. It became clear we were part of a white community that was unprepared for the racialized ruptures that occurred during the weekend. This insight amplified a host of concerns needing redress in our various personal and professional communities. And, unsurprisingly, there were the numerous micro- and macro-aggressions that occur when white communities, and individuals, engage in anti-racist work.

Many important things came out of the weekend, including the recognition that white anti-racists need to develop more racialized stamina and more individual and collective capacity for participating in cross-racial organizing. BIPOC organizers and attendees additionally made it clear that the white organizers in our group had not created a robust enough anti-racist container to hold and attend to the harm and ruptures that occurred during the weekend. In addition, there was a clear call from Resmaa Menakem that white anti-racist-striving individuals need to pivot from focusing on strategies and, instead, invest and dedicate energy and resources toward creating anti-racist cultures. This group was born of that call toward commitment and action.

In the year and nine months after the training, nine of the white members of the planning committee have continued in this work. Group members have met monthly and communicated, often daily, to discuss anti-racist culture and somatic container-building as part of a core commitment to developing embodied racialized stamina. As a group we explore various commitments to developing anti-racist norms and group cultures, work to identity and interrupt white body supremacy in our various contexts and engage in anti-racist imagination projects.

Methods

These commitments to developing and expanding through our own limitations have taken many forms. Some of the anti-racist imagination and culture building projects include: developing and facilitating workshops, organizing anti-racist salons, constructing an audio archive, study groups, community discussions, anti-racist curricula development, incorporation of anti-racist scholarship in somatic therapy trainings, and triad work. Triad work is a somatic pedagogy practice that involves body-oriented focusing to increase racialized distress tolerance and nervous system regulation (Menakem, 2017). We engage in group practices of community-creation – naming and discussing sticking points and grappling together – to increase our capacities to tolerate the distress and discomfort of doing anti-racist work in community. Somatic fortitude and racial stamina are necessary to interrupt the propensity for white individuals to become emotionally dysregulated when confronted with complex and charged conversations about race. This type of reactivity can lead white individuals and groups to inadvertently engage in ineffective emotional processing at the expense of BIPOC. Our group collaborates with others to identify and interrupt white body supremacy culture, develop intersectional white anti-racist cultures, and attend to individual as well as intergenerational and collective traumas.

The Practical

Balancing both internal (personal growth and change) and externally facing anti-racist work (events and trainings), group members have participated in community discussions about anti-racist culture building with other groups and organizations to ensure we interrupt the silo’ing that can occur in anti-racist work. Sub-groups have studied the histories of Antisemitism, as well as racist white feminism, as side projects to sharpen our social-historical awareness.

Internally, we have begun the-long term collective work of identifying and developing communal practices for interrupting the ways white supremacy cultural norms show up in our group. These include hierarchical, top-down decision-making structures, often with white leaders in positions of power, or white norms as guiding principles. These include centering values of ‘professionalism’, ‘civility’ as well as invoking tone-policing and silencing dissent to privilege white comfort. In service of this interruption, we employ a number of rudimentary practices, including practicing leaderful shaping with projects (Raelin, J. A., 2003), and a non-hierarchical group structure. We are also cognizant of white culture-normed reliance on the written word as a primary way of relating. In our meetings, even if virtual (as has been the case through since March 2020), we have begun to include singing, movement, and somatic practices as part of our time together.

After the weekend, Resmaa Menakem tasked the white participants to meet regularly in triads to do embodied exercises from his book in service of developing somatic fortitude. Triad work involving three people—observer, participant, and tracker—is a common component of many somatic, trauma-focused training programs. It is also an integral part of embodied anti-racist culture building. It is clear that it is not enough to identify and name white body supremacy culture, and that groups like ours must also develop robust anti-racist values, norms, and practices. In between monthly meetings we also draw from individual group members’ separate organizing histories. For example, some members’ orientations have historically been focused on anti-fascist organizing. Others have focused on somatic-based healing traditions and its sociopolitical potential. As a group we purposefully examine how these inform our approaches in ways that move us, both towards, and away from anti-racist culture building.

Another way group members develop, and practice anti-racist imagination practices is through outward-facing culture building projects. The public-facing projects demand rigorous inner-facing and interpersonal group work as well. Thus far, a few of these projects include producing an anti-racist salon, creating an audio archive, and a community stickering campaign. The social and collective sensibilities of these projects have invited group members to dream, imagine, and develop new ways of being together.

Practices of community dreaming, imaging, and visioning reconnect individual and community transformation, creating public spaces to hear the imaginal’s critical and creative commentary on our lives. Whereas ideology usually tends to conserve status quo arrangements, utopian imagination brings forward the new, posing a discontinuity. (Kearney, 1998a; Ricouer, 1986, as cited in Watkins & Shulman, 2008, p. 219)

That is, group members have joined together in the work of scheming, sculpting, and envisioning anti-racist collaborations.

Building Anti-Racist Culture: The Salon

Members organized an anti-racist evening salon entitled “Build it And They Will Come” (Appendix A) that brought together (mostly) white folks to sing, dance, write, play and imagine anti-racist worlds and possibilities. We encouraged people to bring their incantations and imaginations to the event and asked those who do not normally perform, or identify as artists, to be involved. We threaded somatic and relational games into the evening, hoping to disrupt the audience-performer binary that reproduces a distanced relationship to art; whereby a piece is produced to be enjoyed (taken in) by an audience. Group members prepared anti-racist fairytales and bedtime stories - imagining a post-white-supremacy landscape for future generations. One member led the approximately 80 attendees through a group sing-a-long to a popular 1980s song with alternate anti-racist lyrics. Another group member shared her piece “A Case for Anti-Racist Fairy Tales” (Appendix B). In it she invited guests to:

Imagine how much change might erupt in just one generation if most, or many, or even just some white babies nestled in loving caregiver arms while sweet words were whispered and songs were sung of a kingdom terrorized by a false supremacy based on a myth of something called “race”... Imagine white babies being sung to as they develop in the womb, swimming in anti-racist amniotic fluid, and listening to lyrics of anti-racist resistance and celebrations sung sweetly from the ether of the other side of the amnion and chorion sac. What kinds of developmentally love-centered, courageous, deeply connected and anti-fascist nervous systems could we manifest?

Much of the evening centered around these communal imaginings of a culture where being explicitly anti-racist is the status-quo. Group members also created and distributed cards explaining the concept of reparations and inviting contributions to a specific local group raising funds for a BIPOC-dedicated, owned, and operated farming and retreat center (Appendix C). The salon aspired to facilitate the experience of being-together, investing in the value of developing our collective and personal affective responses to doing anti-racist practices. That is, the event was a coming together to anti-racist dream and imagine with friends and strangers alike, and then part ways connected in some ways, and detached in others.

Interrupting White Expertise: The Audio Archive

Group members created an audio archive, entitled “Getting Our Cousins”, to collect and share stories about various ways white people have, are, and strive to dismantle and divest from whiteness. The archive interrupts white ‘expertizing’ or ‘elite-ification’ by having audio recordings exist in conversation with one another; using interviews that share and explore the process and messiness of anti-racist culture building. They include various voices to amplify a diversity of perspectives. Interviews are intentionally informal, conversational, and disrupt professional, authoritative and authenticated white-norms of credentialing one’s professional identity.

As the project unfolded, group members grappled with disrupting hierarchies of decision-making, ownership over projects and ideas, and to stymie white-normed impulses to control process and outcomes. The archive also surfaced tensions in the group around various approaches, styles, and sensibilities in anti-racist movement work. These various tensions remain current and led to a pause in the project while group members continue developing communal practices, racial stamina, and anti-racist container building[3] skills. Group members orient toward anti-racist work in many ways, and we strive to allow space for that variety rather than falling into the trap of believing there is ‘one right way’.

Communal Anti-Racist Action: The Stickering Campaign

In the beginning stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, group members mused on ways to engage in collective actions while remaining in spacious solidarity. In an effort to think creatively amidst pandemic restrictions, our group found inspiration in different scholarship regarding the role of art in liberation psychologies. As Watkins and Shulman (2008) describe, “[m]ost liberation psychology projects involve participatory forms of art-making to help awaken new symbols for transformation, seeking to liberate underground springs capable of renewing cultural landscapes” (p. 208).

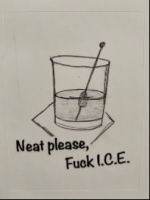

Group members proposed a stickering campaign supporting immigrants’ rights work as an avenue that could inspire consideration of abolitionist approaches to border resistance and immigrants’ rights struggles. The stickering campaign invited people to engage, or post stickers, in various places depending on individual and community comfort, accessibility, and safety. The stickers were intentionally provocative and humorous. The group settled on stickers with the image of a small cocktail glass that read “Neat Please, Fuck I.C.E.” (Figure 1), (Storm; Hirsh, 2020) - using a simple pun referencing a cocktail to call out the American Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s (I.C.E) ongoing violation of human rights and illegal detainment of refugees seeking asylum in the United States. Another sticker included mocking images of instances where ice is necessary, contrasted with the unnecessary presence of I.C.E. (Figure 2), the agency (Prince, 2020). The group then commissioned a local printing press to create these stickers. The company agreed to offer a 15% discount and we invited folks to donate that 15% to La Resistencia, a local grassroots group “working to end the detention of immigrants and stop deportations” (La Resistencia, 2014), specifically at the Northwest Detention Center in Washington State. A letter was then composed by group members Anne Phillips and Cristien Storm (2020) with excerpts from the La Resistencia website (La Resistencia, 2014) to explain the stickering action. The letter included information outlining several avenues for participation alongside resources directing readers to additional opportunities to engage (Appendix D). Tensions emerged as group members wrestled with the reality that each member related differently to realities such as safety, comfortability regarding proximity to legal and illegal activities, and fears of white supremacist backlash to more public-facing aspects of the campaign. These differences also offered opportunities to begin to explore how to develop anti-racist practices, norms and values that support varied positionalities inside whiteness, and various anti-racist lineages. This public-facing action gave us the opportunity to face what Freire termed ‘limit situations’, “...where we are met both as though with an impassable limitation and at the same time given the possibility of finding a new voice, understanding, and way of being-in-the-world” (Watkins & Shulman, 2008, p. 289). These kinds of anti-racist group norms, practices, and values are central to embodied imagination.

Figure 1. Sticker campaign example, image 1

Figure 2. Sticker campaign example, image 2

Discussion

These inward- and outward-facing collaborations and shifting of embodied and affective states has offered numerous possibilities for expanded collective imaginations and has also, at times, collapsed into reflexive white supremacy culture. Woven into this striving toward a divergence from white body supremacy cultural norms is an ongoing movement, or a ‘betwixt and between state’, that Turner (1977) referred to as liminality.

During the liminal period, the group might be stripped of rank and class privileges and characteristics and meet as equal and unique human beings. 'Thus...liminality is frequently likened to death, to being in the womb, to invisibility, to darkness, to bisexuality, to the wilderness, and to an eclipse of the sun or moon'. (as cited in Watkins & Shulman, 2008, p. 137)

This inhabitation of liminal spaces, of attempting to move towards a collective dis-engagement from white-normed ways of being, has led our group into unforeseen

spaces together. This striving has been generative and delightful, as well as painful and distressing. This way of being together has tasked our white bodies with the invitation to engage with the tensions of finding new ways of slowing down, holding novel relational and interpersonal affective states, and developing racial stamina in inhabiting anti-racist imaginal liminal spaces.

New Kinds of Slowing Down

Group tensions around communal doing or being-with have offered opportunities to explore limit situations and liminal spaces intended to produce various forms of anti-racist slowing down. This kind of attending invites group members to interrogate white-normed slowing down which is often an attempt to maintain status quo in response to white body discomfort or dysregulation in doing anti-racist work. Differentiating between white-normed calls for slowing down - which can be rooted in intergenerationally transmuted[4] white fears of destabilization - and more revolutionary calls for change from BIPOC, is critical in being able to name when slowing down is defensive vs. intentional.

The concept of trust is also something for consideration. The group has deliberated around the concept offered by Reverend Jennifer Bailey of Faith Matters Network: ‘Relationships move at the speed of trust, social change moves at the speed of relationships’ (Bailey, n.d.). Members have mused on the invocation offered by Rev. Bailey, including various interpretations of trust and relationships, arriving at no single conclusion and exposing divergent ideologies and approaches to both. These include the desire to slow down and focus on interpersonal and relational trust through engaging in various collaborations. The quest for cohesion around these tensions also reveals disparate ideological approaches to social change existing in the group. Group members rely on trust and affective relational binding to ensure that disagreement in praxis doesn’t result in unnecessary shutting down of connection or the capacity for dialogue; without which collaborations could dissipate or stall due to defensiveness. We hold these latter possibilities in mind in our work, as both can hinder or smother curiosity and collective imaginations. Knowing when, and how, to slow down is our lesson, personally and interpersonally. We continually strive to hold the development of anti-racist practices around a ‘slowing down’ that disrupts white supremacy norms and systemic functions, in service of sabotaging white-normed calls for self-care[5] or inaction.

What we are asking of ourselves, and perhaps inviting other white individuals to do, is to shed the armor of inherited or unconscious white ways of being, and to enter into a place of unknowing, and suffering, in order to transform. Watkins and Shulman (2008) describe this as a state of Regression, borrowing from D. W. Winnicott’s concept, not in the reverting sense but, "a stepping back from busy or manic doing, toward a slower more reflective stance" (p. 135). They describe this as a space where we can grieve, hold space and lean into the suffering. We are, implicitly, tasking ourselves with the invitation to enter this “radical space of pilgrimage” (p. 134), both individually and collectively, so that we may suffer and transform in service of building white anti-racist culture.

Striving to cultivate new kinds of slowing down offers group members an opportunity to develop anti-racist cultural practices which attend to the dysregulation and dis-ease of being in liminal spaces, both together and separately. Because group members are also mostly somatic therapists, this is also an opportunity for future explorations of how to ground somatic and mindful practices of slowing down and co-regulating in embodied anti-racist sensibilities that support racial stamina and interrupt white supremacy culture. Historically, in many white anti-racist organizing, there can be a tension, and at times oppositionality, between engaging in projects or mobilizing actions and interpersonal group work. At times this can imply an adversarial, either/or dynamic, where group members are either doing-together or being-together. Our interrogation of this dynamic invites group members to explore the liminal spaces of doing-by-being-together and relationship-building-by-doing (dreaming, imagining, practicing together). In addition, group members are delving into the somatic stamina and resilience-building that titration between these spaces can offer (Levine, 1997). The hope, then, is that individual and group pendulation between these affective states increases racialized stamina and white body tolerance for embodied and life-long commitments to various forms of anti-racist work.

New Ways of Holding Relational and Interpersonal Space

White bodies are not a monolith. Group members hold a variety of agent and target memberships.[6] It is critical that white anti-racist striving individuals interrupt the reflexive and defensive use of target membership as a mechanism to manage group affect or deflect from engaging in the difficult work of undoing white supremacy culture. Target membership is also real and impacts the ways white bodies are in the world and in anti-racist spaces. Group members struggle with how to cultivate relational connections around target group memberships (and ally or accomplice connections to target memberships) which support the ongoing interrogation of embodied white supremacy culture. A core skill for this kind of intersectional interrogation, or exploring multiple social identities related to positions of power and privilege, is to better track the emergence of reflexive white-normed defensive behaviors that arise when white bodies engage in anti-racist change-work. In addition to tracking, group members are working to engage in what Dr. Leticia Neito calls channel-switching[7], or developing multiple nimble connective capacities based on agent and target memberships. This weaving together, rather than attempting to dismiss various aspects of white group members’ identity, is new to group members.

One challenge group members face is how to navigate and hold different nervous system activations and emotional dysregulation that occur when differently positioned white bodies engage in anti-racist work. This kind of tearing apart and rupturing is what Menakem (2017) calls “burning off”, a necessity for racial stamina and anti-racist culture building. Group members continue to grapple with the challenge of recognizing the interwovenness of embodied white supremacy culture, target/agent memberships, and personal and familial trauma wounds. Many questions have surfaced inside these struggles. We have wondered: How can white people develop interrogation and tracking skills that are nimble enough to tease apart and attend to other experiences of oppression and personal trauma wounds? Is this always necessary? If not, how do group members know and decide when, and if, to do this kind of work? When is tending to these wounds a deflection or other reflexive maintenance of white supremacy culture (and thus a retreat from developing stamina around the activation, discomfort, and distress of doing anti-racist work)? How does a group know when this is white supremacy culture maintaining itself, and/or white fragility disrupting anti-racist work, versus an opening to develop more intersectionality inside white anti-racist culture building work? How can our group hold relational and liminal spaces with relentless compassion and curiosity to explore and then develop communal practices that support this kind of anti-racist interpersonal group development? Most importantly, we do not yet have answers to these questions but engage with them actively as they inevitably show up.

...what I feel is the most important thing is that white bodies have to begin to get into a room with each other, deal with the uncomfortableness, deal with the hierarchy that starts to show up, deal with all the brutality that starts to happen with each other's bodies and then figure out how they're gonna develop culture around beginning to heal that over time… (Menakem, as cited in Langbert, 2019, 12:49)

New Ways of Being-With in Affective States

Developing bonds while in these liminal states invites white bodies to work at the edges of consanguinity and develop new communal binding practices. Collectively, challenges arise around how to hold onto one another in ways that expand individual and collective racialized stamina and anti-racist culture building capacities. In other words, group members have worked to develop practices that support white body pendulation between dysregulation and regulation; between inhabiting anti-racist social spaces and anti-racist psychic spaces. This praxis is in service of expanding individual and communal capacity to tolerate white body discomfort and dis-ease.

Our group is in the formative stages of developing a Psychological Sense of Community (Sarason, 1974, 1988; Fiser et al., 2002; McMillan and Chavis, 1986. p. 75). McMillan and Chavis (1986) describe this as, 'A feeling that members have of belonging, a feeling that members matter to one another and to the group, and a shared faith that members' needs will be met through their commitment to be together’ (as cited in Kagan, et al., 2011, p. 76). Over our time together, members have struggled with belonging as it rises inside individual member’s internal emotional experience as well as our group positionality inside anti-racist social movements. In the initial months, group cohesion seemed centered around the Resmaa Menakem weekend and the call to build anti-racist cultures. In the near two years after the training with Menakem, the nine white anti-racist striving group members have continued to evolve together and grapple with our individual and collective needs for this psychological sense of belonging and community. Group members continue with the deliberate work of building various forms of relational glue and striving toward sustainable white anti-racist cultures.

Conclusion

One of the intentions for this kind of culture and container-building work is to support anti-racist white somatic fortitude that interrupts white supremacy norms inside anti-racist work. Concurrently, we aim to create spaces for white people to emote and express with each other, rather than harming BIPOC people, communities, and spaces. When this deliberate kind of work is not done, the risk is that white bodies will “blow their trauma through bodies of culture”, as Menakem (2017) says. While this container work has happened in small ways throughout the past eighteen months, invariably, there have been numerous challenges.

A lack of historical robust anti-racist cultures, even as our group is beginning to develop, means group norms and practices inevitably fall back on more intellectualized, less embodied and white culture-normed anti-racist interventions. Continuing to integrate imagination praxis into collective work is an ongoing commitment.

In ongoing accountability consultations, our group was tasked to re-focus on developing foundational anti-racist commitments, communal cohesion and trust, and somatic fortitudes. One reflection was that white anti-racist groups often mis-identify how deeply sophomoric our skill and development are with this kind of culture building work. In the authors’ imaginational strivings, we are re-grounding our collective work inside an anti-racist ‘beginner mindset’ with a cultivation of curiosity. This is alongside a commitment to inhabiting liminal spaces together, which may support an increased racial stamina. Additionally, the hope is group members build capacity to divest from white supremacy cultural formations, social arrangements, and group constructions.

The authors hope the manuscript inspires readers to explore anti-racist culture and container building in their particular contexts. As such, we consciously avoided providing readers with a blueprint for how to engage in similar praxis. While it is essential that critical community psychology research and practice enable readers to do this work, we feel the provision of such a prescriptive model would distract from our central message: doing this work requires becoming comfortable with the unknown as it arises. In the authors’ opinion, increasing this distress tolerance is the task for white-bodied individuals.

White bodies need imagination practices that are robust enough to not be crushed under the weight of white supremacy. White supremacy is winning in myriad ways, one of which is snuffing out imagination praxis. It is through this kind of fierce anti-racist imagination praxis that transformation is possible. It is our hope that the culture building practices being developed through our work can be one small contribution to the legacy of critical community psychology and BIPOC imagination practices (both in and outside of academia) upon which all our work stands.

“Our radical imagination is a tool for decolonization, for reclaiming our right to shape our lived reality.”

~adrienne maree brown

NOTES

[1] Anti-capitalist grassroots and community mobilizations (street medics, food not bombs, books for prisoners, blockades, rent strikes, redistribution projects, etc.). Rural organizing project, Institute for Research & Education of Human Rights, Northwest Coalition for Human Dignity, Western States Center.

[2] Racial stamina asks white bodies to develop more skills and capacities to interrogate, interrupt and develop accountability practices for the evasive strategies white people use to avoid their complicity in white supremacy culture.

[3] Container building is a term used by Resmaa Menakem which involves the interpersonal and community building work of people engaged in anti-racist work to create robust enough communities to hold and maintain connection when the charge that arises in confronting white supremacy pushes and, in his words, “blows through bodies.”

[4] Authors consider white supremacy epigenetics or the intergenerational transmission of embodied white supremacy culture.

[5] See Crimethinc.com (2013).

[6] Target and agent membership refers to both Pamela Hays’ ADDRESSING model as well as the work of Dr. Leticia Nieto in her book, Beyond Inclusion, Beyond Empowerment: A Developmental Strategy to Liberate Everyone.

[7] The concept of channel switching comes from the anti-oppression training, somatic improvisational theater and psychodrama work by Dr. Leticia Nieto and refers to times when people switch channels or modes of communication, experience and connection under real or perceived threat.

*Appendices appear after the References*

References

Bailey, J. (n.d.). Faith matters network: Our team. Faith matters network. Retrieved August 10, 2020, from https://www.faithmattersnetwork.org/team

Beed, P., Johnson, A. (2019, August 1). Holistic resistance: Disrupting our whiteness. Holistic resistance. https://www.holisticresistance.com/

Bell, Derrick A. “Who’s Afraid of Critical Race Theory?” University of Illinois Law Review 4 (1995): 893-910.

Boggs, G. L., & Kurashige, S. (2011). The next American revolution: Sustainable activism for the twenty-first century. University of California Press.

Brown, a. m. (2019). Pleasure activism: The politics of feeling good. AK Press.

Butler, O. E. (1993) Parable of the Sower. Warner Books.

Burton, M. (September, 2014). Explaining liberation psychology in English. Paper presentation at the International Community Psychology Conference, Fortaleza, Brazil.

Coates, T. (2014). The Case for Reparations. The Atlantic, 313(5), 54-71.

Freire, P. (1976). Cultural action for freedom. Harvard Educational Review.

Freire, P. (1972). Pedagogy of the oppressed. (M. B. Ramos, trans.) Herder and Herder. (Original work published 1968)

For all we care: Reconsidering self-care. (2013, May 31). Crimethinc.com. Retrieved July 30, 2020, from https://crimethinc.com/2013/05/31/for-all-we-care-reconsidering-self-care?fbclid=IwAR3nx24Dw9ab-WuPUVQiJ_7iDFNziHpKSR76QN59Cgk_NucPZPJS-zU-sA4

Fox, D. & Prilleltensky, I. (Eds.) (1997). Critical psychology: An introduction. Sage.

Fox, D., Prilleltensky, I. & Austin, S (Eds.) (2011). Critical psychology: An introduction (2nd Ed.). Sage.

Hays, P. A. (2008). Addressing cultural complexities in practice: Assessment, diagnosis, and therapy (2nd ed.). American Psychological Association (APA).

Jemisin, N. K. (2016). The fifth season. Orbit.

Kagan, C., Burton, M., Duckett, P., Lawthom, R. & Siddiquee, A. (2011). Critical community psychology. British Psychological Society and Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Kearney, 1998a; Ricouer, 1986, as cited in Watkins & Shulman, (2008). Towards psychologies of liberation. Palgrave Macmillan.

Kelley, Robin D. G. (2002). Freedom dreams: The Black radical imagination. Beacon Press.

Kendi, Ibram. (2019). How to be an antiracist. Penguin Random House LLC.

La Resistencia (n.d.). Shut down the NWDC. La Resistencia. Retrieved August 1, 2020, from http://laresistencianw.org/shut-down-the-nwdc/

Langert, L. (Host). (2019). A conversation on compassion with Resmaa Menakem (9) [Audio podcast episode]. In Conversations on Compassion. University of Arizona: Center for Compassion Studies. https://compassioncenter.arizona.edu/podcast/resmaa-menakem

Leary, Joy DeGruy. (2005). Post traumatic slave syndrome: America's legacy of enduring injury and healing. Uptone Press.

Levine, P. A. (1997). Waking the tiger: Healing trauma: The innate capacity to transform overwhelming experiences. North Atlantic Books.

Lykes, M. B., & Mallona, A. (2008). Towards transformational liberation: Participatory action research and praxis. In P. Reason, & H. Bradbury, (Eds.), Sage handbook of action research: Participative inquiry and practice. (pp. 106-120). Sage.

Lykes, M.B. & Moane, G. (2009). Editors’ introduction: Whither feminist liberation psychology? Critical explorations for a feminist and liberation psychology for a globalizing world. Feminism & Psychology, 19(3), 283-297.

Martín-Baró, I. (1985). The role of the psychologist. (A. Aron, trans.). In A. Aron & S. Corne (Eds.), Writings for a liberation psychology: Ignacio Martín-Baró (pp.33-46). Harvard University Press.

Martín-Baró, I. (1986). Toward a liberation psychology. (A. Aron, trans.). In A. Aron & S. Corne (Eds.), Writings for a liberation psychology: Ignacio Martín-Baró (pp. 17-32). Harvard University Press.

McMillan, D.W. and Chavis, D.M. (1986) as cited in Kagan, C. et al., 2011.

Menakem, R. (2017). My grandmother’s hands: Racialized trauma and the pathway to mending our hearts and bodies. Central Recovery Press (CRP).

Menakem, R. (2020, July 30). About Resmaa. Resmaa Menakem. https://www.resmaa.com/about

Moane, G. (2010). Sociopolitical development and political activism: Synergies between feminist and liberation psychology. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 34, 521-529.

Nieto, L., Boyer, M. F., Goodwin, L., Johnson, G. R., & Collier Smith, L. (2010). Beyond inclusion, beyond empowerment: A developmental strategy to liberate everyone. Cuetzpalin.

Porges, S. W. (2011). The polyvagal theory: Neurophysiological foundations of emotions, attachment, communication, and self-regulation. W.W. Norton.

Prince, S. (2020). [Sticker, “I.C.E is nonessential”]. Artwork. Self-printed.

Raelin, J. A. (2003). Creating leaderful organizations: How to bring out leadership in everyone. Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc.

Storm, C., Hirsh, L. (2020). [Sticker, “Neat Please, Fuck I.C.E.”]. Artwork. Self-printed.

Turner, V. (1967). The ritual process: Structure and anti-structure. Cornell University Press.

Van der Kolk, B. A. (2014). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. Viking.

Watkins, M., & Shulman, H. (2008). Toward psychologies of liberation. Palgrave Macmillan.

Winnicott, D. W. (1989). Psycho-analytic explorations. Harvard University Press.

APPENDICES

Appendix A: Flyer for Anti-Racist Salon Evening

Appendix B: The Case for Anti-Racist Fairy Tales, Cristien Storm, 2020

“Until white people understand that racism is embedded in everything, including our consciousness and socialisation, then we cannot go forward.”

--Robin DiAngelo, White Fragility, Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism

Whiteness is many things: a category of identity, an intergenerational inheritance, a kind of property (resources, access, material gains), a set of privileges, a system of power over and entitlement. Let me be clear, I am not talking about individual white people, but whiteness as it exists as an invention manifested as a brutal reality with a horrific legacy of violence, currently operating in myriad ways. Whiteness, however much an appalling reality for so many, mostly remains invisible to and refused by white people, which rather conveniently upholds and feeds the very real material monster of white supremacy.

There is an urgent need to un-deny whiteness. Urgent because we can never slay the dragon of white supremacy and the growing dragon child white nationalism without white people, white bodies, waking up. We (white folks) need a lot of things to wake up and fight the demons of racism (hell, we need to wake up in order to just use and hear the word racism without freezing or becoming defensive). Fiction, storytelling, songs, lullabies are powerful ways to get us out of intellectualizing, into our bodies, and into spaces of grounded, connected, collective liberation. It is not enough to talk, write, think, about white supremacy, we white bodies must imagine the death and destruction of something invisible to us. We must help steward the annihilation of something we have been taught to not see AND we must do this work while also conjuring radical future possibilities. We do not need to heal whiteness or find ways to redeem white culture, we need to be death doulas and steward white supremacy and with it, whiteness to its passing over into rich verdant soil so seeds smothered by white culture violence and hatred can finally sprout and grow. This does not mean ignoring the present reality of white privilege and white supremacy. We must be fully grounded in the brutal reality of white supremacy and wake up every day committed to resisting it. We must also look beyond its construction. This means practicing saying no to what we don’t want and yes to the kinds of worlds we want to create. We must, in other words, practice imagining. Fairy tales are one way to practice and develop our anti- racist imagination muscles.

Stories drop bodies into present oriented experiences of past and future events. This kind of presence, of being in and with while staying here and now, opens up wild spaces for transformation, healing, and of new kinds of possibilities. This is why truth telling and story sharing are at the heart of many kinds of healing practices. This is not the same as reliving or retelling traumatic events, which survivors are asked to do all the time in the name of justifying their experience, but about collective meaning and possibility making.

Stories, songs, lullabies can transform us, change our bodies, our nervous systems and alter our relationship to the present, the past and the future. That is some powerful magic.

Developing anti-racist stories is challenging for white folks because whiteness is invisible and racism and white supremacy are relegated to specific kinds of violent acts (by bad and racist

people) and not talked about as a deeply ingrained, embodied, and historical culture and the institutions and systems that uphold it. All kinds of stories can help white people begin to see the invisible, challenge the “non-existent”, and develop fierce anti-racist cultures.

Fairy tales entertain, but the main purpose is to impart moral lessons that listeners metabolize, internalize, and embody. Fairy tales are, in other words, culture builders. They have been used to uphold, normalize and mainstream Christianity, heterosexuality, capitalism, white supremacy, why not anti-racist and anti-fascist culture jamming through fairy tales and storytelling?

“We are in an imagination battle...Imagination gives us borders, gives us superiority, gives us race as an indicator of ability...and I must engage my own imagination in order to break free.”

adrienne maree brown, Emergent Strategy: Shaping Change, Changing Worlds

Imagine how much change might erupt in just one generation if most, or many, or even just some white babies nestled in loving caregiver arms while sweet words were whispered and songs were sung of a kingdom terrorized by a false supremacy based on a myth of something called “race”.

All the white babies breathed in the noxious air of these lies that made them feel superior and in turn encouraged them to create organizations and institutions based on this imagined feeling of superiority and entitlement, which lead to violence, despair, isolation, disembodiment, fragility, rigidity, and some really bad music and psychological diagnostic systems. Some babies surrendered to the lie, while others developed resistant nervous systems that refused to submit to the deceptions. These white babies developed anti-racist anti-bodies that flooded their systems making them speak truth to power, truth to one another, truth to authority, truth to lies and dishonesty, truth to rivers, oceans, of white supremacist saline solutions that have poisoned every water system, helped white bodies regulate, helped them step up to authority, step into communities and gave them x-ray vision to see the invisible threads that bound this false ideology together and wove it into all the institutions that were created.

Imagine white babies being sung to as they develop in the womb, swimming in anti-racist amniotic fluid, and listening to lyrics of anti-racist resistance and celebrations sung sweetly from the ether of the other side of the amnion and chorion sac. What kinds of developmentally love-centered, courageous, deeply connected and anti-fascist nervous systems could we manifest? Imagine white bodies that can blow antiracist microbes into water systems.

Imagine some culture jamming millennial hacking into digital spaces altering every single baby music soundtrack to include anti-racist/anti-fascist lyrics.

Whale sounds and the cries of a dying white supremacy

Fluttering flutes and falling fascism in all iterations

Birdsong and stories of John Brown

Waterfalls, windsongs, and whispered tales of women like Lydia Maria Child

Bells, chimes, and abolitionist dreams of women like Elizabeth Margaret Chandler

Imagine the nervous systems of those infants, fiercely grounded in visions of possibilities we white folks are just beginning to realize we need to remember so we can practice and develop more possibilities. White voices resonant with the clarity and conviction of antiracist imaginaries ready to dream and do, resist and revive.

Imagine making capitalism a, “Once upon a time there was a system of never-ending extraction and expansion based on some people taking whatever they wanted and justifying their taking by making up a wild thing called race.” Some people came to believe this fiction that permeated everything, but others, brilliant bad ass story tellers and vision makers, warriors, healers, medicine folks, architects, scientists, witches, rose and made potions and cast spells that made the invisible systems visible and people grabbed all kinds of tools and smashed, and kicked, and screamed and sang, and meditated and loved that horrible system out of existence. The water cleansed and the land healed. And now, we share this story so we don’t ever forget that we manifested a monster and must never do it again. To never forget that we created an invisible beast and we need to remember it’s vital organs, it’s weak points, so that we know exactly where to strike should it ever try to rise up again.

Imagine the collective power and creative force of the kinds of no. NOT EVER’s that could be generated with white nervous systems that didn’t have to do thousands of hours of diversity training before committing to collective action. Now.

Just picture the kinds of delicious Yes! and Hell YES!’s that would emanate from these kinds of white bodies. The songs, the stories, the games, the memes, the party themes, the dance playlists, the dinner parties, the picnics, the institutions, systems, the buildings, the art shows, the paintings, the schools, theater productions, dance moves, and music classes…imagine…the delight, the joy, the ability to be here now and to dream there now. Just imagine the futures those bodies could dream. Then manifest.

Just imagine. Then sing.

Appendix C: Reparation Card for Anti-Racist Salon

Appendix D: Copy of Letter For Stickering Action

Hi friends!

We are reaching out to folks to see if they have the interest and capacity to host a sticker party in support of immigrants’ rights work that is, among many things, calling for the release of families detained at the Tacoma Detention Center.

Why are we doing this?

What is a sticker party?

You order a roll of stickers from Girlie Press at quote@girliepress.com

Put: Girlie Press - Quote No 33870 in the subject line

In your email make sure to include:

We have three images--you can get one or all of them! We included those below as well.

The prices listed below are for a roll of one image--there is a combo discount for orders over 5,000 if you want to throw a really big sticker party! Girlie Press is giving us a 15% discount and you generously donate that 15% to La Resistencia. The pieces listed below are the regular rate so you would be able to take 15% off that to donate to La Resistencia here:

http://laresistencianw.org/donate/

You drop off or mail stickers to friends and family who stick them up wherever you all can to generate awareness about the necessity of immediately releasing people from the Tacoma Detention Center and the overall need to abolish criminal and carceral responses to immigration. The sticker party is one small action that supports a national call to shutdown immigration detention centers across the country. Why is this important?

(from Take Action by La Resistencia)

The NWDC is one in a network of over 200 facilities across the country where migrants are caged. Ending the practice of caging migrants will require concerted action, and this shut-down campaign is part of a national strategy to challenge the existence and expansion of immigrant detention. Shutting down the NWDC, one of GEO Group’s “flagship” facilities, would send a powerful message to the private prison industry and the federal government, and more importantly, to the thousands fighting detention centers across the country and along the border, that ending immigration detention is within our reach. Central to the fight to shut down the NWDC are efforts to free all who are detained there, and to support those who may be transferred elsewhere when the facility closes. When there are fewer prisons for immigrants, fewer immigrants are arrested and detained. We can see this if we compare Washington, Massachusetts and Georgia. These states have similar size immigrant populations, but Massachusetts has less than half the detention capacity of Washington. According to TRAC, ICE made about half as many arrests in Massachusetts (3760) as they did in Washington (7139). In contrast, Georgia has a similar size immigrant population but twice as much immigrant detention infrastructure, and 3.5 times as many ICE arrests (25,137). If we dismantle the infrastructure that allows for easy detention of our neighbors and family members, we expect less immigration enforcement in this state.

Sticker options:

See attached images and price and quantity info below

1. Estimate Number 84178.1

Finished Size: 3 x 4

Quantity & Price

[1] 250..................$329.90

[2] 500..................$391.00

[3] 1,000..................$493.20

2. Estimate Number 84178.2

Finished Size: 3 x 4

Quantity & Price

[1] 2,000..................$629.70

[2] 3,000..................$846.30

[3] 5,000..................$1,049.30

Figure 1. Sticker campaign example, image 1 |

Figure 2. Sticker campaign example, image 2 |

Appendix A: Flyer for anti-racist salon evening |

Appendix C: Reparation card for anti-racist salon |

Gloria Dykstra and Cristien Storm

Gloria Dykstra and Cristien Storm

Gloria Dykstra, is an activist-scholar and licensed mental health therapist in Seattle, Washington, who works from an anti-racist, anti-oppression, liberatory framework. Her philosophy on individual psychotherapy is informed by liberation and community psychologies as well as somatic approaches to trauma healing. Originally receiving her Masters in Existential-Phenomenological Therapeutic Psychology, Gloria found her way to Liberation Psychology after working in the community mental health sector for 4 years. She became interested in the discordance between providing low-barrier mental health therapy and the realization that the very systems of provision were perpetuating harm in the marginalized communities they aimed to help. In 2008, Gloria co-founded The Coalition of Therapists for Justice as an aspirational community response to this tension. She works in private practice in Seattle, WA, USA and Vancouver, B.C. where her client work is focused on decolonizing our ways of relating to emotional distress and moving alongside clients toward healing generational and racialized trauma.

Cristien Storm, is a writer, activist and politicized mental health therapist with a long history of integrating arts and cultural organizing into anti-racist and anti-fascist activism. She is the author of Empowered Boundaries: Speaking Truth, Setting Boundaries and Inspiring Social Change. Her writing has appeared in numerous publications including Perspectives on Anarchist Theory journal and Against The Current magazine. Cristien is a co-founder and former Executive Director of Home Alive, where she developed and facilitated self-defense and boundary setting curricula rooted in marital arts, social justice, and anti-oppression sensibilities. She is also a co-founder of If You Don’t They Will, a Northwest collaboration that provides concrete and creative strategies to counter white nationalism through a cultural lens which includes creating spaces to generate visions, hopes, desires, and dreams for the kinds of worlds we want to live in.

agregar comentario

![]() Descargue la versión en PDF para acceder al artículo completo, incluyendo tablas y figuras.

Descargue la versión en PDF para acceder al artículo completo, incluyendo tablas y figuras.

palabras clave: racial justice, praxis, critical liberation, anti-racism