Community programs for domestic violence (DV) in the U.S. have historically focused on White populations. Few programs exist to meet the needs of racial/ethnic minority populations, including Latinx women, who encounter greater barriers to access services than their non-Hispanic White counterparts. Casa de Esperanza is one of the few organizations in the U.S. focused on addressing the unique needs of Latinx survivors of DV. In particular, their Family Advocacy Initiative (FAI) seeks to support Latinx communities impacted by DV by facilitating a variety of services including a 24-hour hotline, shelter, community advocacy, and transitional housing support network. This program utilizes Casa de Esperanza’s Latina Advocacy Framework, which was developed to address the unique risks, considerations, and needs of Latinx communities, but has yet to be empirically evaluated. As part of a graduate community psychology course on assessment, consultation, and evaluation, a university-community partnership was established to explore the process of defining, designing, and planning an evaluation of Casa de Esperanza’s FAI. This paper describes the university team’s process in learning about Casa de Esperanza and the FAI and collaboratively developing an evaluation plan. We briefly summarize the program’s theory of change, review its logic model, and present results from a focus group conducted with program staff. Based on this information we discuss the evaluation and recommendations for implementing it. Throughout the paper, we highlight the need for culturally sensitive programs for survivors of DV and the importance and benefits of collaborative community partnerships and evidence-based evaluative learning.

Download the PDF version to access complete article, including Tables and Figures.

Background

Women of all races experience intimate partner violence (IPV) – referred to as domestic violence (DV) when it occurs within the home (e.g., Benson, Woolredge, & Thistlethwaite, 2004; Cho, 2012; Grossman & Lundy, 2007). These terms and their acronyms (i.e., DV/IPV) are often used interchangeably to describe experiences of physical, sexual, and/or psychological violence, as well as stalking by a current or former intimate partner (Breiding, Basile, Smith, Black & Mahendra, 2015).[1] Historically, DV intervention programs have emphasized helping survivors leave their abusive partner in order to secure safety. However, when examining the issue of DV among Latinx immigrants specifically, studies have documented a number of unique cultural, structural, and institutional barriers that influence decisions about staying with or leaving abusive partners, and/or seeking services and support (e.g., Alvarez & Fedock, 2016; Ingram, 2007; Vidales, 2010). These barriers may increase their vulnerability to continued exposure to violence and trauma.

Predominantly, studies have found that immigration status, limited English proficiency, traditional gender-based and family norms, and financial instability greatly influence Latinx survivors’ decisions to seek help and/or report the abuse to authorities (e.g., Reina, Lohman, and Maldonado, 2014; Vidales, 2010). For instance, in a qualitative study on the experiences of Latina immigrants who faced DV, over 20% of Latina survivors of DV identified limited English proficiency as their main barrier to seeking and receiving the help they needed (Vidales, 2010). Ingram (2007) found first-generation (i.e., foreign-born) Latinx immigrant survivors of DV are less likely to access formal help than both their second-generation and their non-Hispanic, White counterparts. Although not directly measured, Ingram (2007) identified problems related to immigration status (e.g., fear of deportation) as potential underlying causes for the limited formal help-seeking behaviors. Furthermore, Latinx survivors of DV that do access services are more likely to do so after longer periods of experiencing abuse and are likely to experience more severe mental health consequences of abuse (e.g., Caetano & Cunradi, 2003; Edelson, Hokoda, & Ramos-Lira, 2007; Gonzalez-Guarda et al. 2011; Klevens, 2007). For example, Edelson and colleagues (2007) found that Latina women experienced lower self-esteem, more severe trauma-related symptoms, and more severe depression symptoms following abuse than did non-Latina women.

Despite increasing evidence for the unique socio-cultural barriers impeding help-seeking behaviors and service utilization among Latina survivors of DV, interventions to support survivors of DV have historically and predominantly been developed with and geared toward White, English-speaking, non-immigrant populations (e.g., Barner & Careney, 2011; Bograd, 2007; Pence, 1983; Roberts, 2007; Shepard & Pence, 1999). Only in recent decades has cultural sensitivity been considered and incorporated into DV programs and interventions (Barner & Carrney, 2011; Gondolf & Williams, 2001; Hampton, LaTaillade, Dacey, & Marghi, 2008; Ragavan, Thomas, Medzhitova, Brewer, Goodman, & Bair-Merritt, 2018). Such interventions are better equipped to support Latinx survivors because they treat DV as a multidimensional problem. These programs approach DV as a public health issue that stems from the maladaptive social relations between intimate partners that might be experiencing additional stressors unique to their cultural contexts. Thus implementers of culturally sensitive interventions need to have deep knowledge of issues that may impact Latinx survivors, such as systemic racism, immigration status and restrictive immigration climate/policies, language barriers, cultural orientation or identity, and acculturation, among others (e.g., Dutton, Orloff, & Hass, 2000; Klevens, 2007; Rodriguez et al., 2018). Culturally sensitive programs and organizations, such as Casa de Esperanza, have been at the forefront of providing services that incorporate the many unique cultural and contextual issues present in the lives of Latina survivors (Serrata, Rodriguez, Castro, & Hernandez-Martinez, 2019). Such interventions identify the role of culture early in the initiative planning stage and incorporate it into the framework of the intervention at every subsequent stage of development and implementation. For example, a culturally sensitive intervention would not only address survivors’ individual needs, but also extend services to family members and provide education about immigration options for immigrant Latina survivors (Perilla, Serrata, Weinberg, Lippy, 2012). Additionally, program staff might actively engage community leaders, especially cultural or religious authorities, and invite them to serve as mediators between providers and participants in order to develop collaborative relationships and practices. Evidence for the effectiveness of culturally sensitive interventions for Latina survivors of DV is growing. These programs have been found to foster a sense of empowerment (Serrata, Macias, Rosales, Rodriguez, & Perilla, 2015; Serrata, Hernandez-Martinez, & Macias, 2016), self-esteem (Fuchel & Hysjulien, 2013; Fuchel, Linares, Abguttas, Padilla, & Hertenberg, 2016), and psychological well-being for Latinx survivors (Serrata, Rodriguez, Castro, & Hernandez-Martinez, 2019).

Current Study

Research suggests that creating a comprehensive evaluation plan that incorporates contextual realities improves evaluation quality and conducting program evaluation helps ensure that programs are evidence-based (e.g., Chatterji, 2004). The goal of this project was to generate an evaluation plan for Casa de Esperanza’s Family Advocacy Initiative (FAI) that accounts for the cultural and organizational context that is so critical to the program’s success. The project emerged from a graduate community psychology course on Assessment, Consultation, and Evaluation (ACE). A university-community partnership was established leveraging university resources to develop an evaluation of the efficacy and success of the FAI. The university team was composed of four community psychology doctoral students and one community psychology faculty member with expertise in program evaluation, and the community team was composed of Casa de Esperanza leadership and FAI staff members. This partnership included consistent communication between university team members and FAI management and staff members to gain a clear understanding of the problem of DV among Latinx survivors, daily initiative operations, overarching initiative goals, and existing measures for assessing initiative success.

As part of this process, the university evaluation team conducted a focus group with FAI advocates (see subsequent section) to collaboratively operationalize program activities, program outcomes, and current limits to and strengths of program evaluation capacity. Informed by qualitative analysis of these data, the university evaluation team assisted Casa de Esperanza leadership in the production of a logic model that matched latent community processes and mechanisms of change to the FAI’s manifest operational activities and overarching program goals of DV harm reduction and future violence prevention among Latinx women. To provide context, we first briefly describe the framework within which Casa de Esperanza approaches DV, including the components of this multi-faceted and long-standing culturally sensitive DV intervention program. We then present findings from a focus group conducted with staff members tasked with implementing the FAI, and summarize recommendations for the final evaluation plan, operationalizing how FAI’s theory of change links program activities to measurable indicators. A Secondary Research on Data or Biospecimens application was submitted to Georgia State University’s Institutional Review Board (IRB). The project was exempt from IRB approval given that data were previously collected for non-research purposes.

The Family Advocacy Initiative at Casa de Esperanza

The Family Advocacy Initiative (FAI) is Casa de Esperanza’s core program, which includes direct services and support structures for Latinx families experiencing DV. Specifically, the FAI includes: a 24-hour crisis shelter with advocacy, a 24-hour bilingual crisis phone line, transitional housing support, roving advocacy (i.e., meeting survivors in their homes or community settings to share information and resources), and referrals to other service providers.

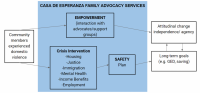

The FAI uses Casa de Esperanza’s Latina Advocacy Framework (LAF; Casa de Esperanza, 2013) to guide how FAI advocates work with, support, and advocate for Latinas who have experienced DV. Based on more than twenty-five years of DV advocacy, this framework emphasizes the importance of maintaining a cultural lens in order to deeply understand Latinx realities which center all programmatic activities. The LAF describes two key pieces of successful Latinx advocacy: (1) advocates must maintain a depth of Latinx cultural knowledge, understanding, and appreciation, which are supported by (2) organizational policies, procedures, and services designed to embrace and build on Latinx cultural realities. The central tenets of the FAI’s advocacy framework are also reflected in their theory of change, which highlights the importance of promoting knowledge of rights and systems, facilitating access to services, and providing culturally appropriate support to Latinx survivors of DV. These core elements are meant to empower survivors and help them successfully transition from a state of crisis to more long-term planning. The ultimate goal is safety and stability, which is achieved through access to necessary crisis interventions and resources. Additionally, attitudinal change and independence/agency are facilitated through interactions with and support from bilingual and bicultural advocates working within the LAF. These advocates empower participants to advocate for themselves and independently navigate systems relevant to their stated goals including safe housing, legal justice, immigration relief, mental health, increased income, stable employment, and opportunities to advance their future(see Figure 1 for a visual representation, download the PDF version to access the complete article, including Tables and Figures).

Insights from the Advocate Focus Group

As part of the evaluation team’s effort to understand the full scope of Casa de Esperanza’s FAI, a focus group was conducted with nine of the 10 full-time advocates to assess their unique perspectives about the implementation and success of the program. A flexible questioning route (Kruger & Casey, 2015) was used to guide the group discussion around four general areas: (1) goals of the program (e.g., how do you know that the program is successful?), (2) participant needs (e.g., how do you assess the needs of each participant?), (3) advocate role (e.g., what is your day-to-day like? In what ways could the program best support its advocates?), and (4) feasibility of follow-ups (e.g., is there a system in place to follow-up with participants?). The meeting lasted about an hour and was audio-recorded with permission from the advocates. Using a phenomenological approach (Creswell, 2014), responses were later assessed to form categories of comments and ideas, which are referred to as themes (described below). Advocates were open and engaged throughout the meeting and expressed excitement at the idea of developing an evaluation plan for the FAI. Their commitment to the FAI and the communities they serve was evident in their responses and their willingness to collaborate with the research team. This all may indicate that the acceptability and feasibility for conducting the proposed evaluation will be high.

Theme (1): Long-term Orientation as Success

Many advocate comments related to perceptions of program goals and participant outcomes that represent these goals. In particular, advocates seemed to agree that the program’s fundamental goal is to establish participants’ safety and stability over time. Advocates repeatedly highlighted that this goal involves more than just addressing participants’ immediate, short-term needs (e.g., shelter) but also helping them gain confidence in their ability to advocate for themselves and develop and pursue long-term goals (e.g., GED, savings). For example, one advocate noted that, “When participants come in at first, they say, ‘can you call the clinic for me?’, or, ‘can you find me an interpreter?’, but after they’ve been through advocacy and they begin to understand that they can navigate these systems, they start to say, ‘I’ll call them, it’s no big deal.’ They start doing it for themselves and that’s when we know it [advocacy] is working.” Notably, for advocates, success of the Family Advocacy Initiative is “... more than just meeting [participants’ stated] goals, like finding stable housing or getting an order for protection, although it’s that, too. It’s helping them realize they have the power to get out of this and to be safe and happy.”

Theme (2): Operational Details

Throughout the discussion, advocates described the details of day-to-day operations and discussed their work in practical terms. Generally, advocates reported an average workload (in terms of number of participant cases they manage at a given time) of between 25-30 participants per advocate, which they described as challenging but manageable. Advocates also described two key advocacy processes, (1) intake and needs assessment, and (2) case termination and follow-ups, which are described as sub-themes below.

Sub-theme: Intake and Needs Assessment Process. Advocates generally described the intake process as long, with a number of demographic variables to record and many ‘boxes to check.’ In response to the question, how do you assess participant needs? advocates were quick to note that each participant is a unique human being and must be treated as such rather than as a case to manage. Advocates further noted that participants are often in a state of crisis at the time of their intake, and; therefore, advocates are faced with the difficult task of providing emotional support while also trying to appropriately and accurately assess participant needs – a task which advocates do not often feel fully prepared for (this will be discussed further in Theme (3).

Sub-theme: Case Termination and Follow-Ups. Advocates reported that there is no formal protocol for closing a case. Instead, advocates noted that it is up to the discretion of the advocate and supervisor to determine when an individual is no longer an active participant of the FAI. One advocate stated, “Usually, a case is closed if the participant has met their goals, says they don’t need services anymore, or if we just can’t get into contact with them anymore.” Additionally, in response to the question, how feasible would it be to conduct follow-up calls with participants after their cases have been closed? (in order to follow-up on long-term outcomes), advocates reported quite firmly that it would not be feasible given their already high workloads. The caveat was added, however, that it is a good idea and could be implemented if new hires were made for that purpose.

Theme (3): Increased Structural Support

Throughout the focus group advocates expressed their unanimous support for the work that the organization is doing in general, and within the Family Advocacy Initiative, in particular. Although advocates expressed pride in being part of the Casa de Esperanza community and to be able to help participants in such tangible ways, they also expressed dissatisfaction with some aspects of the program and identified ways in which these could be improved. These were further categorized into two subthemes: (1) record-keeping, and (2) increased training and support.

Sub-theme: Record-Keeping. Advocates generally seemed to think that the intake and needs assessment process is currently too unwieldy. Advocates described the intake forms as “inorganic and cumbersome,” and their database as not user-friendly, noting that the information they are required to record is mostly demographic in nature, likely for funding reporting purposes, and not particularly relevant to participant needs or goals. One advocate noted, “it’s just too much red tape.” Advocates also mentioned that the previously reported lack of formal protocol for tracking participant goals and needs often leaves them relying on ‘their head’ or their own informal/unofficial records to remember all the information. Advocates stated that all of this makes it difficult for them to listen to participants and be fully present with them at the time of their intake. The following quote summarizes this concern, “It’s like, I want to listen to the participant, but because I have of all these reporting requirements, I end up having to continuously write down little details that actually have nothing to do with assessing or addressing what the participant needs.”

Sub-theme: Increased Training and Support. Advocates suggested that there are a few areas in which they could use more support at the organizational level, and that these improvements would make them more effective and productive in their work. For example, advocates reported that, for many of them, their advocacy position is their “first job in the field.” As such, they described thinking that specialized training for how to respond to DV at the start of the position would be very helpful. Advocates also suggested training for specific issues that are commonly found among participants’ situations (e.g., training in legal issues, common psychological responses to trauma typical for DV, immigration procedures). Finally, advocates expressed interest in receiving further support and training to mitigate job burnout and compassion fatigue, which are frequently reported problems in helping professions, particularly for those who respond to survivors of trauma (e.g., Killian, 2008). One statement especially embodied this sentiment, “There’s a lot of compassion fatigue and just a lot of hard emotions that go on as advocates… we need to hold advocates up. We have high turnover because of the burnout, and we need to address that.”

Evaluation Plan and Design

In order to effectively capture success within the FAI, the university team designed an evaluation plan that includes a broad spectrum of methods, such as participant and advocate narratives, as well as quantitative measurements. Importantly, this plan was informed by and responsive to the concerns as well as suggestions made by advocates during the focus group discussion. In particular, when developing this plan, we remained mindful of advocates’ expressed interest in receiving additional support and resources, including additional staff, to help with data collection and management. Thus, in developing recommendations, we sought to limit wherever possible the addition of new evaluation components that would add to advocates’ record keeping burden. For example, we emphasized the use of existing administrative records and forms, such as the FAI’s intake and exit interview forms. In some cases, we recommended ways of enhancing the data that were already being gathered (e.g., converting yes/no questions to Likert-type scales). In other cases, we suggested incorporating scientifically valid psychosocial measures, recognizing that additional resources directed toward evaluation would be needed to supplement the existing data collection. Thus, the recommended evaluation plan takes advantage of the wealth of qualitative observations from interviews and reports that FAI advocates and other staff members do as part of their practice. The plan offers options tailored to specific logic model outcomes for use with current data and measurement infrastructure. It also offers options for expanding data measurement, collection, and management procedures to support ongoing advocacy and to create a more holistic and accurate assessment of program components and their success. By establishing means to capture both quantitative and qualitative data, this evaluation plan provides a platform for accurate evaluation of program outcomes and impacts through a depth and variety of information. In the next section, we describe the process that the university team engaged in when reviewing the FAI’s logic model and offer recommendations for refining it and for strengthening outcome measurement.

Review and Refinement of FAI’s Logic Model

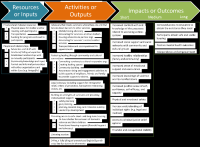

In addition to conducting the focus group, the university team reviewed a draft logic model that was developed by Casa de Esperanza leadership in collaboration with FAI staff members (see Figure 2, to see Figure 2 download the PDF version to access the complete article, including Tables and Figures). This initial draft clearly considered evidence-based recommendations for effective program logic modeling (e.g., see W. K. Kellogg Foundation, 2004), and was critical in helping the university team gain a greater understanding of how core program components were linked to expected outcomes. In the next section, we offer an ‘outsider’s perspective’ to recommend modifications to the logic model. Broadly, our recommendations were intended to help the initiative more clearly align each impact/outcome with a specific activity/output, and link elements of the logic model to specific evaluation strategies. We also offer suggestions about where additional data collection is needed, both before and after program participation, to evaluate the effectiveness of outputs. Finally, we make recommendations to ensure that clear and consistent language is used throughout in order to enhance the usefulness of this tool for future evaluation efforts.

A key outcome in the FAI’s logic model is that participants will gain comfort with and knowledge of the processes related to accessing various systems. Given the importance placed on this outcome, we suggested that it would be valuable for an evaluation to obtain rich information about the nature and extent of knowledge gained by participants. We recommended building on the existing measure, which is limited to a single yes/no question from an exit interview protocol. The question asks participants to report whether, as a result of the program’s support, they have developed further knowledge of available community resources. A simple enhancement would be to incorporate a five-point, Likert-type scale ranging from Not at All to Very Much to capture the extent to which participants perceive their knowledge and understanding of a given system has increased as a result of the program’s support. The question could also be added to a baseline and periodic assessment throughout the client’s participation as a means of monitoring change over time.

Two related key outcomes include (a) increased social support and social networks with community and cultural groups, and (b) increased sense of emotional support and reassurance. These outcomes highlight the critical role that social groups such as family, friends, and community members play in the well-being of survivors of DV. Although there is currently no formal protocol in place for assessing perceived social support, the FAI team could rely on observational data (from the advocates) to determine whether these goals are being met.

With the additional use of validated measures of social support (e.g. the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (Zinat et al., 1988), advocates could ascertain, document, and quantify (e.g., determine quality of support from family members, count number of close friends) participants’ social support networks after each contact session or after a predetermined period of time.

Another key outcome involves increased healthy relationships (family and community). This outcome emphasizes the importance of social networks – with particular focus on family and community relationships – for fostering resilience among Latinx survivors of DV. Currently, the FAI team relies primarily on qualitative observations from the advocates to assess this outcome, which as described by the advocates during the focus group meeting, are not systematically recorded. Instead, each advocate relies on their own informal/unofficial records to track this data. Although valuable, qualitative observations that are not documented may make it difficult to accurately assess and track progress over time. Therefore, our team recommended Casa de Esperanza/FAI leadership develop a formal protocol for documenting qualitative observations and other advocate notes (see next section on broad recommendations), and complement such observations with validated measures of quality of romantic relationships (e.g., Investment Model Scale; Rusbult, 1998) and of sense of community (e.g., Psychological Sense of Community Scale; Jason, Stevens, & Ram, 2015) in order to better understand and assess participant progress and program success.

Further, the program’s expected goals of increasing (a) knowledge of violence and its manifestations, (b) understanding of individual rights, and (c) positive sense of self, confidence, self-efficacy, and capacity all promote survivor empowerment and self-advocacy. At present, these outcomes are not being formally assessed. It was our recommendation that the program add questions to the Intake and Exit Interview forms to assess these outcomes pre- and post-participation in the program, and to again complement such data with validated measures whenever possible. The evaluation team also recommended that the program take an active role in providing psychoeducation to participants by offering psychoeducational materials, workshops, or coordinating guest presentations on the topic.

The program’s overarching goal is to address the needs and concerns of participants by empowering them to cultivate and sustain a life of agency and safety. To better assess efficacy for this goal, we also recommended that FAI staff conduct follow-ups to evaluate if concerns and needs participants presented at the time of intake have been remedied, and whether gains in safety have been maintained post-participation in the program.

Broad Recommendations for the Evaluation Design

To best support the continued success of this comprehensive program, the implementation of the following recommendations will be helpful in establishing a sustainable evaluation plan that allows easy and complete assessment of the achieved goals and processes involved. It is important to note that whereas the research team prioritized and considered sustainability and feasibility throughout the process (e.g., by relying on and maximizing existing resources), the implementation of some of these recommendations may require additional resources, including additional staff, and all of them will require organizational appreciation of the utility of a program evaluation as a means of program improvement.

a. User-friendly data entry form templates could be employed to allow advocates to enter new data directly into a central database (specific recommendations were provided to the organization in an oral presentation of evaluation findings. A list of these is available upon request).

b. Additionally, several recommendations were provided for analytical approaches and computations necessary to evaluate the types of questions using the various forms of information. These suggested resources were provided to the organization and are available upon request.

Implementing these recommendations would gather valuable information to improve the efficacy of the FAI but would also come with some risks to participant confidentiality. Systematically collecting and recording additional information about participants, particularly after participants have left the program, may present additional pressures on the FAI staff to keep that information, and thereby participants, safe. Although most DV agencies do include confidential paperwork, many of the evaluation-specific measures recommended above can be deidentified or aggregated after collection to preserve participant privacy. In addition, instituting clear data management protocols and training for all advocates would help the FAI maintain confidentiality for participant data.

Conclusions and Lessons Learned

In this concluding section, we offer brief reflections, conclusions, and lessons learned from the student research team, the instructor, and the lead evaluator from Casa de Esperanza.

Students

For students in the community and clinical-community psychology programs at GSU, first formal exposure to the practice of community psychology often happens in the context of a class project such as the present evaluation. This was the case for most members of our student team. As second and third year graduate students in the program, we were excited for the opportunity to translate the theoretical knowledge we had gained from foundational community psychology courses and research into practice through the development of an evaluation plan for a well-established national organization that exemplifies many of the tenets of the field. Indeed, Casa de Esperanza is a long-standing organization serving a need for culturally sensitive services for Latinx survivors of DV. Core community psychology practice competencies and value propositions such as empowerment, socio-cultural, and cross-cultural competence, among others (e.g., Dalton and Wolfe 2012; Ratcliffe and Neigher, 2010) are evident in all their initiatives, including (and perhaps especially) the FAI. In the process of reviewing formative program materials, engaging in ongoing communication with organization leadership, and conducting a focus group of family advocates, we gained valuable insights into the practice of community psychology. We believe this experience facilitated effective learning and professional development, as well as helped solidify our interests in developing, implementing, and/or evaluating community-based initiatives.

Instructor

This consultation with Casa de Esperanza is an example of a successful project to introduce students to community psychology practices that align with their career goals (Kuperminc, Chan, Seitz, & Wilson, 2016). In ACE, we work to create a ‘win-win,’ in which students gain valuable experience while community partners gain a valued and tangible product that they might not have had the resources to accomplish on their own. A less obvious outcome is that these projects serve to deepen long standing relationships with community organizations that program faculty and students have worked with over the years, and to establish new partnerships. In this case, three of our faculty members have worked closely with Casa de Esperanza starting more than 10 years ago in work that has involved multiple graduate and undergraduate students. Two alumni have gone on to full-time employment with Casa de Esperanza. In fact, one of those alumni (the 5th author of this article), served as the main point of contact for the current consultation project (see Community Partner reflections below).

As an instructor for ACE, I have learned that successful projects like this one are built on laying the groundwork up front, including transparency about strengths and limitations with regard to student time and previous experience, as well as establishing as much as possible a clear and feasible set of goals and expectations, and emphasizing shared ownership of and responsibility for the work. Toward that end, I ask that community partners provide a brief (typically one paragraph) description of the project they have in mind and meet with the class (either in person or by video conference) for an hour to kick off the project. Student teams then take the lead, building a collaborative working relationship, learning about the organization, defining specific deliverables, and reporting results. Individually, students also maintain a journal of their experiences, structured in a way that bridges their experience in the field with topics covered in class readings throughout the semester (e.g., planning an evaluation, selecting criteria, research design, ethical considerations). As the instructor, I try to provide enough ‘scaffolding’ to help students work through the process while allowing for an authentic experience that includes all the inevitable bumps in the road. In the end, my hope is that students emerge from this experience ready to take the next step to more independent projects.

Community Partner

We have a great deal to learn from culturally specific, community grounded programs such as the FAI, which are often engaging in creative and innovative approaches to meet the needs of survivors. Casa de Esperanza is home to the National Latin@ Network (NLN) for Healthy Families and Communities, the federally designated cultural resource center on DV and Latino communities (Domestic Violence Resource Network, 2017). Through the NLN we provide training, technical assistance, research, and public policy advocacy to better serve Latinas and their families. Part of this work includes providing evaluation support and evaluation capacity building with Latino-serving and culturally specific DV organizations. The partnership described in this paper is an example of how evaluation can be used as a tool to document and lift up culturally specific practices into the broader DV field, which has not always been supportive of approaches to DV work that fall outside mainstream White feminist models (Starr, 2018). There are many organizations – especially those run by and for communities of color – that lack the resources or internal capacity to evaluate their innovative practices and many have had negative experiences with external researchers and evaluators. Thus, it has been important to ensure that the evaluators we partner with are grounded in community psychology principles and are as open to learning as the students involved in this project were.

Casa de Esperanza’s many programs have previously benefited from the assistance of student evaluators, but this partnership was the first to engage the FAI specifically. Prior to the current partnership with GSU ACE students, the FAI staff (the 6th and 7th authors of this article) and I, the director of the researcher and evaluation center for the NLN and alumni of the GSU community psychology PhD program, had begun a participatory approach to evaluation. We worked together to outline the initiative, develop the logic model, and inventory their current evaluation practices. In addition to serving as a gentle introduction to evaluation, this pre-work modeled participatory evaluation and set the stage for working with external evaluators. In our first meetings with the students, it was important to set clear expectations for the scope of the project. We emphasized the importance of ensuring that any evaluation plan and tools developed would need to fit within the program context. For example, some of the grants that support the FAI require their own data collection forms to be used for evaluation. The students heard our concerns and conducted a web-based focus group with FAI staff to learn more about the current limitations and structures that might impede a successful implementation of the evaluation. In addition, the staff who participated in the focus group shared their appreciation for the opportunity to offer direct input and be part of evaluating the impact of their work on survivors. The findings from the focus group document the real need for more advocates to fulfill the high demand of advocacy support and services for survivors of DV. Overall, the rich partnership between Casa de Esperanza and GSU, setting clear expectations for both the scope of work and the evaluation approach used facilitated a positive experience for our FAI staff. We look forward to the chance to improve and enrich our work and to be able to share Casa de Esperanza’s unique approach to working with Latina survivors of DV.

References

Alvarez, C., & Fedock, G. (2016). Addressing intimate partner violence with Latina women: a call for research. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 1524838016669508.

Barner, J. R., & Carney, M. M. (2011). Interventions for intimate partner violence: A historical review. Journal of family violence, 26(3), 235-244.

Benson, M. L., Wooldredge, J., Thistlethwaite, A. B., & Fox, G. L. (2004). The correlation between race and domestic violence is confounded with community context. Social Problems, 51(3), 326-342.

Bograd, M. (2007). Strengthening domestic violence theories: Intersections of race, class, sexual orientation, and gender. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 25(3), 275–289.

Caetano, R., & Cunradi, C. (2003). Intimate partner violence and depression among Whites, Blacks, and Hispanics. Annals of epidemiology, 13(10), 661-665.

Cameron, S., & turtle-song, i. (2002). Learning to write case notes using the SOAP format. Journal Of Counseling & Development, 80(3), 286-292. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2002.tb00193.x

Casa de Esperanza (2013). Latina Advocacy Framework: National Latin@ Network for Healthy Families and Communities A Project of Casa de Esperanza.

Cattaneo, L. B., & Chapman, A. R. (2010). The process of empowerment: A model for use in research and practice. American Psychology, 65, 646-659. doi:10.1037/a0018854

Chatterji, M. (2004). Evidence on “what works”: An argument for extended-term mixed-method (ETMM) evaluation designs. Educational Researcher, 33(9), 3-13.

Creswell, J. W. (2014). Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Domestic Violence Resource Network (2017). Organizational Descriptions. Retrieved from https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/fysb/dvrn_descriptions_20170420.pdf

Dutton, M., Orloff, L., & Hass, G. A. (2000). Characteristics of help-seeking behaviors, resources, and services needs of battered immigrant Latinas: Legal and policy implications. Georgetown Journal on Poverty Law and Policy, 7(2), 245-306.

Edelson, M.G., Hokoda, A., & Ramos-Lira, L. (2007). Differences in effects of domestic violence between Latina and non-Latina women. Journal of Family Violence, 22:1–10.

Fuchsel, C. L., & Hysjulien, B. (2013). Exploring a domestic violence intervention curriculum for immigrant Mexican women in a group setting: A pilot study. Social Work with Groups, 36, 304-320. doi:10.1080/01609513.2013.767130

Fuchsel, C. M., Linares, R., Abugattas, A., Padilla, M., & Hartenberg, L. (2016). Sí, Yo Puedo Curricula. Affilia: Journal of Women & Social Work, 31, 219-231. doi:10.1177/0886109915608220

Gondolf, E., & Williams, O. (2001). Culturally focused batterer counseling for African American men. Trauma, Violence and Abuse, 2(4), 283–295.

Gonzalez-Guarda, R.M., Vasquez, E.P., Urrutia, M.T., Villarruel, A.M., & Peragallo N. (2011). Hispanic women's experiences with substance abuse, intimate partner violence, and risk for HIV. Journal of transcultural nursing: official journal of the Transcultural Nursing Society / Transcultural Nursing Society, 22(1):46–54. [doi].

Grossman, S. F., & Lundy, M. (2007). Domestic violence across race and ethnicity: Implications for social work practice and policy. Violence Against Women, 13(10), 1029-1052.

Hampton, R., LaTaillade, J., Dacey, A., & Marghi, J. (2008). Evaluating domestic violence interventions for black women. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 16(3), 330–353.

Ingram, E. M. (2007). A comparison of help seeking between Latino and non-Latino victims of intimate partner violence. Violence against women, 13(2): 159-171.

Jason, L. A., Stevens, E., & Ram, D. (2015). Development of a three?factor psychological Sense of Community Scale. Journal of Community Psychology, 43(8), 973-985. doi:10.1002/jcop.21726

Killian, K. D. (2008). Helping till it hurts? A multimethod study of compassion fatigue, burnout, and self-care in clinicians working with trauma survivors. Traumatology, 14(2), 32-44.

Klevens, J. (2007). An Overview of Intimate Partner Violence Among Latinos. Violence Against Women, 13(2), 111–122. https://doi-org.ezproxy.gsu.edu/10.1177/1077801206296979

Kruger, R. & Casey, M. (2015). Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

McWhirter, E. H. (1994). Counseling for empowerment. Alexandria, VA: American Counseling Association.

Pence, E. (1983). The Duluth Domestic Abuse Intervention Project. Hamline Law Review 6, 247-275.

Perilla, J. L., Serrata, J. V., Weinberg, J., & Lippy, C. A. (2012). Integrating women's voices and theory: A comprehensive domestic violence intervention for Latinas. Women & Therapy, 35(1-2), 93-105.

Ragavan, M. I., Thomas, K., Medzhitova, J., Brewer, N., Goodman, L. A., & Bair-Merritt, M. (2018). A systematic review of community-based research interventions for domestic violence survivors. Psychology of Violence. https://doi.org/10.1037/vio0000183

Reina, A. S., Lohman, B. J., & Maldonado, M. M. (2014). 'He said they’d deport me’: Factors influencing domestic violence help-seeking practices among Latina immigrants. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 29(4), 593-615. https://doi-org.ezproxy.gsu.edu/10.1177/0886260513505214

Roberts, A. R. (2007). Battered women and their families: Intervention strategies and treatment programs, 3rd ed. (A. R. Roberts, Ed.). New York, NY: Springer Publishing Co.

Rodriguez, R., Macias, R. L., Perez-Garcia, R., Landeros, G., & Martinez, A. (2018). Action research at the intersection of structural and family violence in an immigrant latino community: A youth-led study. Journal of Family Violence. https://doi-org.ezproxy.gsu.edu/10.1007/s10896-018-9990-3

Rusbult, C. E., Martz, J. M., & Agnew, C. R. (1998). The Investment Model Scale: Measuring commitment level, satisfaction level, quality of alternatives, and investment size. Personal Relationships, 5(4), 357-391. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6811.1998.tb00177.x

Schwarzer, R., & Jerusalem, M. (1995). Generalized Self-Efficacy scale. In J. Weinman, S. Wright, & M. Johnston, Measures in health psychology: A user’s portfolio. Causal and control beliefs (pp. 35-37). Windsor, UK: NFER-NELSON.

Serrata, J. V., Hernandez-Martinez, M., & Macias, R. L. (2016). Self-empowerment of immigrant Latina survivors of domestic violence: A promotora model of community leadership. Hispanic Health Care International, 14(1), 37-46. doi:10.1177/1540415316629681

Serrata, J. V., Macias, R. L., Rosales, A., Rodriguez, R., & Perilla, J. L. (2015). A study of immigrant Latina survivors of domestic violence: Becoming líderes comunitarias (community leaders). In O. M. Espín, A. L. Dottolo, O. M. Espín, A. L. Dottolo (Eds.), Gendered journeys: Women, migration and feminist psychology (pp. 206-223). New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1057/9781137521477.0019

Serrata, J. V., Rodriguez, R., Castro, J. E., & Hernandez-Martinez, M. (2019). Well-Being of Latina Survivors of Intimate Partner Violence and Sexual Assault Receiving Trauma-Informed and Culturally-Specific Services. Journal of Family Violence, 1-12. doi:10.1007/s10896-019-00049-z

Shepard, M. F., & Pence, E. L. (Eds.). (1999). Coordinating community responses to domestic violence: Lessons from Duluth and beyond (Vol. 12). Sage Publications.

Starr, R. W. (2018). Moving from the mainstream to the margins: Lessons in culture and power. Journal of Family Violence. https://doi-org.ezproxy.gsu.edu/10.1007/s10896-018-9984-1

Vidales, G. T. (2010). Arrested justice: The multifaceted plight of immigrant Latinas who faced domestic violence. Journal of Family Violence, 25(6), 533-544.

W.K. Kellogg Foundation Logic Model Development Guide. (n.d.). (2004). Retrieved from https://www.wkkf.org/resource-directory/resource/2006/02/wk-kellogg-foundation-logic-model-development-guide. Used with permission of the W.K. Kellogg Foundation.

[1] In this paper, the term DV is used to be consistent with the language used in the Casa de Esperanza program.

Figure 1. FAI Theory of Change |

Figure 2. FAI Logic Model |

M. Alejandra Arce, Daniel W. Snook, Hannah L. Joseph, Miklós B. Halmos, Rebecca Rodriguez, Rosario de la Torre, Teresa Burns, & Gabriel P. Kuperminc

M. Alejandra Arce, Daniel W. Snook, Hannah L. Joseph, Miklós B. Halmos, Rebecca Rodriguez, Rosario de la Torre, Teresa Burns, & Gabriel P. Kuperminc

M. Alejandra Arce, is a doctoral candidate in the Clinical and Community (CLC) psychology concentration at Georgia State University. She received a Bachelor of Arts in Psychology from Florida International University, Honors College. Her graduate research has focused on immigrant well-being, and she is particularly interested in investigating multi-level contributors to resilience and positive developmental outcomes among immigrant youth of color.

Daniel W. Snook, is a doctoral candidate in the Community Psychology program at Georgia State University. He earned a B.S. in Psychology from the University of Florida Honors College. Currently, he is working with advisor Dr. John Horgan and the Violent Extremism Research Group (VERG). His research framework is a mix of applied social and community psychology.

Hannah L. Joseph, is a doctoral candidate in Clinical and Community Psychology at Georgia State University. She earned her bachelor’s degree in Latin American Studies from Oberlin College and her master's degree in Psychology from Georgia State University. Her research focuses on developing resilient communities to support adolescents throughout development, with a particular emphasis on youth violence prevention.

Miklós Balázs Halmos, is a Community Psychology doctoral student at Georgia State University. Miklós is currently working on his dissertation project examining the role of sexual minority stress in the perpetration of aggression among sexual minority individuals. His graduate research under Dr. Dominic Parrot is focused on examining both individual and community, and temporal and proximal, risk and protective factors for perpetrating and falling victim to aggression and violence.

Rebecca Rodriguez, served as Manager and then Director of Research and Evaluation at Casa de Esperanza from 2016 to 2020. She is a Community Psychologist whose research interests broadly focus on culturally-specific and community-centered approaches to prevent family violence in Latin@ families.

Rosario de la Torre, is the Co-Director of the Family Advocacy and Community Engagement program at Casa de Esperanza. She came to the United States from Mexico in 1988 and is a highly experienced and respected advocate in the fields of domestic violence and sexual assault. She was a primary contributor to the development of the Latina Advocacy Framework and provides training to other advocates and organizations across the country.

Teresa Burns, is the manager of Casa de Esperanza’s Refugio program providing safe shelter for Latin@ women who have experienced domestic violence. Her work focuses on providing holistic and culturally-specific support at the Refugio as well as on Minnesota’s only 24-hour bilingual crisis line.

Gabriel P. Kuperminc, is Professor of Psychology and Public Health at Georgia State University where he serves as director of the doctoral program in community psychology and chairs the university’s new interdisciplinary initiative, Resilient Youth (ResY), which emphasizes a resilience perspective to study and develop interventions to reduce health disparities among urban youth.

agregar comentario

![]() Descargue la versión en PDF para acceder al artículo completo, incluyendo tablas y figuras.

Descargue la versión en PDF para acceder al artículo completo, incluyendo tablas y figuras.

palabras clave: program evaluation, community advocacy, domestic violence, cultural sensitivity