The internet allows people to connect with virtually anyone across the globe, building communities based on shared interests, experiences, and goals. Despite the potential for furthering our understanding of communities more generally through exploring them in online contexts, online communities have not generally been a focus of community psychologists. A conceptual, state-of-the-art review of eight major community psychology journals revealed 23 descriptive or empirical articles concerning online communities have been published in the past 20 years. These articles are primarily descriptive and can be organized into four categories: community building and maintenance (seven articles, 30.43%), community support (six articles, 26.09%), norms and attitudes (six articles, 26.09%), and advocacy (four articles, 17.39%). These articles reflect a promising start to understanding how we can utilize the internet to build and enhance communities. They also indicate how much further we have to go, both in understanding online communities and certain concepts regarding community psychology more generally. Community psychologists involved in practice and applied settings specifically may benefit from understanding online communities as they become integral components of advocacy, community organizing, and everyday life.

Download the PDF version to access the complete article, including Tables and Figures.

The concept of “community” is multifaceted and has evolved alongside communities themselves throughout history (Krause & Montenegro, 2017). The advent of the internet is considered by some the largest increase in expressive capability in human history (Shirky, 2009). Fully 95% of U.S. teens have access to a smartphone, a strong trend across gender, race, socioeconomic status, and parents’ level of education (Anderson & Jiang, 2018). As of 2019, 73% of adults aged 65 and older use the internet, while 100% adults aged 18-29 use the tool. (Pew Research Center, 2019). Our understanding of communities—and the concept of community itself— are being transformed and will continue to change as the use of the internet continues to grow (Castells, 2001; Nip; 2004; Reich, 2010).

The internet is profoundly changing how we create and interact with knowledge (Wesch, 2009) and how we build and maintain personal relationships and communities. Much like there is no universal agreement on what makes a community, there is no universal agreement on what it means to have an online community, although a recent attempt suggests the following definition:

An online community is constituted by people who meet together in order to address instrumental, affective goals and at times to create joint artefacts. Interaction between members is mediated by internet technology. In order to constitute community members’ need to: show commitment to others; experience a sense of connection (e.g., members need to identify themselves as members); exhibit reciprocity (e.g., the rights of other members are recognised); develop observable, sustained patterns of interaction with others; and show the necessary agency to maintain and develop interaction. Community creates consequences which are of value for members (Hammond, 2017).

Social networking sites like Facebook and Reddit often are the platforms for online communities, but users of those sites may also not take part in, regularly interact with, feel connected to, or identify with a particular or any online group or community. Notwithstanding disagreement around what communities truly are, Madara (1997) argued community is more easily found, chosen, or started online than face-to-face. For example, people with chronic illnesses or disabilities might benefit from online communities because such communities are often more readily accessible, and online community members can be judged more by their contributions and not their status or appearance (Cole & Griffiths, 2007).

Within practice settings, community psychologists have explored online training (Arcidiacono, Procentese, & Baldi, 2010; Scull, Kupersmidt, & Weatherholt, 2017) and social networking sites (Lenzi et al., 2015). Others have discussed how community psychologists might create mutual-help forums (Pita, 2012) or online forums where community members can discuss upcoming and recent programs (Shull & Berkowitz, 2005), and use social media (Brunson & Valentine, 2010; Crichton & Burmeister, 2017; Jimenez, Sánchez, McMahon, & Viola, 2016; Kia-Keating, Santacrose, & Liu, 2017; Tebes, 2016). Still others have explored how social media can be used in harmful ways (Garaigordobil, 2017; Santisteban & Gámez-Guadix, 2017).

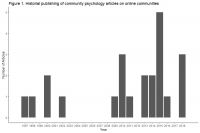

A small but inconsistently growing body of literature within community psychology has focused specifically on the emergence of online communities (Figure 1). In the Handbook of Community Psychology (Bond, Serrano-García, & Keys, 2017), relevant literature regarding online communities comes from outside of community psychology journals (Figueroa Sarriera & González Hilario, 2017; Krause & Montenegro, 2017). In this article, we examine existing community psychology literature and suggest future directions for practitioners and researchers.

The central questions for this modified conceptual, state-of-the-art literature review (Grant & Booth, 2009) are:

Method

While we are aware of literature on online communities outside of community psychology, our focus in this review is on work published in community psychology journals. We chose to look solely at community psychology-related journals as they serve as an approximate proxy for the importance of online communities to the field. Additionally, it would be difficult to impossible to follow every community psychologist’s publishing record to find if they had possibly published on online communities in a journal outside of community psychology. In short, we seek to identify how much has been published and what is known about online communities in English language community psychology journals and what major themes have been explored. Since we are interested in the number of articles published to date as well as their content, we aim to provide a modified conceptual, state-of-the art literature review (Grant & Booth, 2009).

To this end, the first author searched for the terms “online community,” “virtual community,” “internet community,” and “social media” in the following eight major English language community psychology journals: American Journal of Community Psychology, Australian Community Psychologist, Community Psychology in Global Perspective, Global Journal of Community Psychology Practice, Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, Journal of Community Psychology, Journal of Prevention and Intervention in the Community, and Psychosocial Intervention. Any article published before or during 2018 was considered.

To be included in this literature review, articles needed to discuss how people use technology platforms intended for or with potential for online communities, including but not limited to forums, listservs, and social media. We were not interested in papers strictly about online usage (e.g. using the internet to find information). After identifying an article, we reviewed the abstract for relevance, then the full article for those selected from their abstracts. Finally, references were reviewed for any potentially missing articles. All three authors reviewed each article for inclusion and classification. Articles were classified by all three authors inductively, derived from the themes discovered within the articles rather than predetermined conceptualizations (Braun & Clarke, 2006). The authors established reliability through consensus; all three authors had to agree an article belonged in a category. Taken together, the authors had significant experience with qualitative research coding, with preparation of literature reviews and with online communities. These qualities support the credibility of the review process and the results presented here.

An article could cross multiple categories. For example, it is easy to imagine a study about how communication norms vary across advocacy groups or an intervention testing how different community building and maintenance strategies affect members’ perceptions of support. We assigned papers to the category most closely aligned with the study’s examined variables and/or outcomes. Thus, a paper examining communication norms among members of an online support group would be considered a publication on communication norms, not community support.

Results

In response to the first research question regarding the number of publications on online communities in community psychology journals, this literature search returned 23 descriptive or empirical articles published in community psychology-related journals anytime between 1997 and 2018. The distribution is somewhat bimodal; six of the articles (26.09%) were published between 1997 and 2002; no articles were published between 2003 and 2008; and 17 articles (73.91%) were published in 2010 or later (See Figure 1). Also, no articles were found prior to 1997. In response to the second research question regarding the topics considered, four categories emerged: community building and maintenance (seven articles, 30.43%), community support (six articles, 26.09%), norms and attitudes (six articles, 26.09%), and advocacy (four articles, 17.39%) (to access Table 1, see PDF version to access the complete article, including Tables and Figures). Community building and maintenance refers to the creation and upkeep of communities. Community support is defined as care and assistance—emotional, instrumental, tangible, or financial—given and received by community members. The norms and attitudes theme include ways members of a community discuss ideas with one another, communicate what is appropriate in those contexts, and think about and interact with outside groups. Finally, advocacy means attempts by a group to garner public support for a cause or policy important to their community. The results described below outline the findings of the 23 articles we found.

Community building and maintenance

The largest category, community building and maintenance, houses seven articles addressing the creation and conservation of communities (See Table 1). Researchers explored a message board for third culture and missionary children (Loomis & Friesen, 2011), children on children-focused social media sites (Reich, Black, & Korobkova, 2014), older Chinese migrants communicating with friends and family in China (Li, Hodgetts, & Sonn, 2014), users of social media sites like Facebook (Niland, Lyons, Goodwin, & Hutton, 2015; Reich, 2010), World of Warcraft (WoW) players (O’Connor, Longman, White, & Obst, 2015), and technology use among people experiencing homelessness in Madrid (Vázquez, Panadero, Martín, & del Val Diaz-Pescador, 2015). Most of these studies are descriptive in nature, although one—Reich (2010)—directly tested hypotheses.

Loomis & Friesen (2011) studied an online community of adult “third culture kids,” people who grew up in a culture other than their parents’ native cultures or the one in which they have a passport. Members came together from across the globe to influence the website’s functioning, community regulations, and norms; provide support for one another; and develop sense of community. They disclosed life updates and stories with one another, engaged in efforts to meet with one another offline, assigned ambassadors to recruit new members, and shared information.

Similarly, Reich et al.’s (2014) three-year longitudinal study examined how users build community in nine online communities aimed at children (e.g. Club Penguin, Webkinz, Gaia). Even when online communities were designed to restrict communication, users still found creative ways to share personal information and emotions with one another, show affiliation, and gather in large groups. Reich and colleagues identified three key components contributing to sense of virtual community: membership, i.e., a sense of belonging; influence, i.e., the sense one affects the community and its members; and immersion, i.e., a state of flow during community navigation. These studies highlight the ability to form communities even when members do not know each other offline, and even with restrictive site policies limiting communication.

Online technologies can allow users to stay connected with previously established in-person networks while building new ones, and/or allow them to supplement communication with offline networks, creating hybrid communities. Interviews with older Chinese migrants to New Zealand revealed technology’s role in allowing migrants to maintain ties to China while adapting to their new environment (Li et al., 2014). Utilizing Skype allowed them to talk with family members and friends. Simultaneously, the migrants forged the “Chinese-Kiwi Friendship Programme” to foster greater connection and belonging in their new neighborhoods. Technology allowed overseas Chinese people in New Zealand to maintain ties with their homeland communities while creating relationships in person in their new locales.

Similarly, Niland and colleagues’ (2015) descriptive study challenged the notion that online interactions do not foster friendships. Focus groups with existing friend groups found overlap between online and offline interactions. Participants agreed friendship requires being open and genuine, which can be accomplished through status updates (although these may also be inauthentic and annoying). Friends deterred social misuse of the internet by preventing others from talking badly about their friends or posting negative comments, and by helping with privacy concerns (e.g. helping make a distinction between fun and embarrassing pictures).

Not having access to communication technology can not only make the internet unavailable, but also affect one’s ability to navigate various communities and keep in touch with family and friends (Vázquez et al., 2015). Interviews with individuals experiencing homelessness in Madrid indicated involvement with communication technologies, but the percentage of those using cell phones (59%) is well below that of the general population of Spain (94%). Lower cell phone usage makes interacting with government agencies, who increasingly expect the public to use these technologies, more difficult. Individuals experiencing homelessness also have trouble keeping in touch with family who live outside Madrid. Even individuals experiencing homelessness who do utilize these technologies experience social exclusion, although it is unclear to what extent they experience social exclusion compared to their counterparts without these technologies. It is also unclear whether social exclusion could be alleviated with an improvement of free public access to these technologies.

While some studies suggest online technologies allow for community creation, social media can also muddy the waters of online community. Reich (2010) synthesized data from four projects with high schoolers and college students as participants and found mixed evidence for a sense of online community in these hybrid communities. There was little evidence for membership through boundaries (people were Facebook friends with people they barely knew), emotional safety (due to drama), and identity (no evidence of a “MySpace/Facebook identity”). There was evidence of immersion via personal investment. Reich found mixed evidence for integration and fulfillment of needs: there was little evidence of shared values, although there was agreement on norms and shared purpose. There was also mixed evidence for shared emotional connection, as users could experience both connection and isolation while on the sites.

On the other hand, a study of current and past World of Warcraft (WoW) players’ sense of community, social identity, and social support indicated these qualities can be found among WoW players (O’Connor et al., 2015), despite the low likelihood of players knowing one another offline. WoW was a common ground, and players enjoyed feeling a part of a broader, massively multiplayer online (MMO) game community. More specifically, World of Warcraft players identified as gamers, WoW players, and guild members (i.e., members of in-game groups who often play together). Through the game, World of Warcraft players were able to obtain in-game help, advice about offline concerns, and emotional support, with many players trusting their guildmates. As a result, O’Connor and colleagues (2015) propose the degree to which someone identifies with a community may affect their sense of community.

Since community building has been described as a way to operationalize community psychology’s values (Lazarus, Seedat, & Naidoo, 2017), we would expect community building and maintenance to loom large in our literature on online communities. Likewise, the literature in this section reflects the ambiguity in the concept of community building. Researchers have utilized various models and measures for a general sense of community (Jason, Stevens, & Ram, 2015; McMillan & Chavis, 1986; Nowell & Boyd, 2010). Many perspectives on sense of community abound; as such, it makes sense to find parallel concerns surrounding definition and measurement for online sense of community.

Parallel to the offline world, context matters when online. Some social networking sites may focus more on networked individualism, i.e., communication emphasizing individuals’ distinctiveness, rather than communication positioning them within communities (Reich, 2010). Even sites emphasizing networked individualism serve a need for interpersonal connections. All communities highlighted in these studies reflect a bottom-up or community-based approach in their development and maintenance. We can see a desire for community (Li et al., 2014; Loomis & Friesen, 2011; Reich et al., 2014), but there are challenges specifying exactly what this means regarding online worlds and how technology can affect our sense of community in general. Further exploring what factors contribute to building strong online communities will help community psychologists reach a deeper understanding of online sense of community. One avenue to explore is community support.

Community Support

Six articles considered community support, specifically the internet’s potential to be used to obtain support, often by members of groups historically seen as marginalized or isolated. These primarily descriptive articles explored support in online communities composed of people with diabetes (Barrera, Glasgow, McKay, Boles, & Feil, 2002); lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals in Hong Kong (Chong, Zhang, Mak, & Pang, 2015); single young mothers (Dunham et al., 1998); cardiac patients (Dyer, Costello, & Martin, 2010); those with disabilities (Obst & Stafurik, 2010); and those in alcohol recovery (Bliuc, Doan, & Best, 2018). In these studies, community support comprised of and arose from activities like sharing personal information, experiences, and emotions; chatting with others in real time; expressing one’s identity; providing or receiving guidance or moral support; providing or receiving empathy, sympathy, or comfort; and providing or receiving physical, financial, or material assistance.

Across these disparate groups, similar themes emerged. In particular, online support group participants perceived increased availability of social support (Barrera et al., 2002; Chong et al., 2015; Obst & Stafurik, 2010). Additionally, online communication helped some members develop a sense of group membership or receive social support, which they may not have been able to accomplish offline (Bliuc, Doan, & Best, 2018; Chong et al., 2015; Obst & Stafurik, 2010). Those who were more socially isolated were more likely to consistently participate (Dunham et al., 1998). Higher access to the online community was associated with various positive outcomes, such as greater wellbeing, a stronger sense of community, a stronger sense of online social support, and lower stress levels (Bliuc, Doan, & Best, 2018; Dunham et al., 1998; Obst & Stafurik, 2010). A stronger sense of community was also associated with personal growth and better relations with others (Obst & Stafurik, 2010).

Even when higher levels of participation were not associated with reduced depression, anxiety, and stress, and/or increased perceived interpersonal support, or social network size, they were positively associated with perceived benefits of using forums. These benefits included but were not limited to learning from others, understanding others with similar experiences, and being reminded one is not alone (Dyer et al., 2010). Dyer and colleagues do make a distinction between what active participants and “lurkers,” or those who are online but do not offer and receive support, may experience; active participants may receive greater satisfaction from the online community.

These articles echo previous findings around social support. According to Saegert and Carpiano (2017), social support facilitates wellbeing and physical and mental health in the face of stress. Online communities may facilitate giving and receiving support to and from those in similar situations and provide opportunities to build relationships and create social networks. Taken together, these initial findings suggest the potential for online communities to foster social support and sense of community. A next step is to examine which features of online communities produce these results. One feature may involve communication norms.

Norms and Attitudes

Six studies examined norms and attitudes in different online and hybrid contexts. Researchers explored communication norms among users of the social networking site Bebo (Whittaker & Gillespie, 2013), problem drinkers (Klaw, Dearmin Huebsch, & Humphreys, 2000), and those with depression (Salem, Bogat, & Reid, 1997). A comparative study examined how bodies are discussed on a pro-anorexia (pro-ana) and an anorexia recovery sites (Riley, Rodham, & Gavin, 2009). More recently, studies highlighted attitudes and meta-stereotypes within certain communities, in this case specifically gaming-related communities (Nic Giolla Easpaig, 2018; Steltenpohl, Reed, & Keys, 2018).

A 12-month longitudinal study examining 37 Scottish young people’s Bebo profiles qualitatively analyzed how users self-present and evaluate self-presentations, and how they interacted with other users on Bebo in prescribed and non-prescribed ways (Whittaker & Gillespie, 2013). Users often “guest edited” each other’s profiles, and the style of communication was targeted to the in-group and was almost unintelligible to out-group members. Users often brought their Scottish accents to their online “utterances,” and abbreviations were often used. Community members created words to show/request a strong relationship between two people.

Message boards and listservs may or may not be monitored but can provide a sense of privacy through intimacy and disclosure. Online support groups may support processes for emotional support, information/advice, help-seeking, affective responses, and self-disclosure (Klaw, Dearmin Huebsch, & Humphreys, 2000; Salem et al., 1997). Posts tend to feature high rates of self-disclosure and support, which might alleviate shame and provide opportunities for people to compare their experiences. Professionals tended to post infrequently, highlighting a difference with face-to-face environments where professionals more typically make inputs altering group processes with some frequency. The most active users tended to become informal moderators/leaders and were less likely to address their own issues, taking more of a helping role. They were more likely to address posts to individual users, provide emotional support and cognitive guidance, and show social support. Overall the findings from these two studies suggest norms of emotional support and self-disclosure in online mutual support groups.

The stated purpose of communities may have an impact on how individuals interact with them. For example, one study examined differences in communication norms concerning body talk on a pro-anorexia (pro-ana) and an anorexia recovery site (Riley, Rodham, & Gavin, 2009). Almost all members were female. On the pro-ana site, members often included their weight in their post signatures. The recovery site forbade including numbers, so members used workarounds to indicate size more vaguely. Weight gain was seen as problematic on both sites, but on the recovery site it was better if it was limited or “for health.” On the pro-ana site, discussions about members’ bodies were usually detailed and reframed negative experiences into positive ones. On the recovery site, bodily descriptions were more about difficult and tentative movement away from behaviors/thoughts relating to eating disorders. The results of this study support embodiment (that users pay attention to and describe their body) on the internet, specifically that internet might not be a “bodiless environment” after all. Previous qualitative studies outside the field, including disability studies (e.g, Seymour, 2001), have conceptualized the internet as a place where embodiment can occur.

Sometimes online contexts can mirror offline contexts in problematic ways. Nic Giolla Easpaig (2018) found discussions around gender-based harassment in online gaming communities mirrored many of the ways these discussions have emerged in offline contexts. Specifically, conversations around sexism in online gaming spaces focused on the misrecognition of behaviors often deemed acceptable within these contexts as sexist, a tentative acceptance of gender as a salient component of gender-based harassment within gaming communities, and a focus on authenticity of membership (whether women are “real gamers” or not).

A study examining the meta-stereotypes of a hybrid community, the fighting game community (FGC), found members felt generally misunderstood by people outside of the FGC, and felt especially misunderstood by non-gaming-related media (Steltenpohl, Reed, & Keys, 2018). FGC members believed these negative perceptions largely come from a reliance on outdated stereotypes and a lack of research into the community.

These articles highlight the predictable and powerful influence of norms and attitudes. When members help one another, there appear to be strong bonds of connection, for example, for those with alcohol issues and for those dealing with depression. On the other hand, online communities can often mirror offline contexts in problematic ways, particularly when it comes to discussions and norms around sexism and stereotypes. Future research might examine what factors encourage norm and attitude development, and if and how these norms and attitudes can lead to a greater sense of community. We might examine whether we can change those patterns, especially if they become ineffective or harmful. Understanding this area of research may be helpful in maximizing community efforts at collective action, particularly regarding advocacy and resistance against oppression.

Advocacy

Online communities can be used to advocate for causes important to community members. Four articles examined how social media and the internet could be used to organize advocacy efforts. Two of these were descriptive articles exploring advocacy through the lens of specific issues, particularly labor relations (Brady, Young, & McLeod, 2015) and schizophrenia (Menon, 2000). The other empirical articles examined how engagement with the internet may affect how someone engages in the political process (Alberici & Milesi, 2013) and barriers and facilitators to diffusion processes—that is, individuals’ knowledge of and decision to adopt new ideas—within a youth-led online network (Kornbluh, Watling Neal, & Ozer, 2016).

Labor organization UNITE HERE networked with social workers, academics, and allies to pressure the Society for Social Work Research to relocate their conference, in response to low wages for workers at Hyatt Hotels in San Antonio (Brady et al., 2015). UNITE HERE created a strategy and used multiple social media tools to meet short-term goals, like identifying allies, raising awareness, and building community allied communities. Similarly, in the schizophrenia discussion group SCHIZOPH, a poster shared a story about a woman with schizophrenia who failed to pay for a cup of coffee ($0.79) and was arrested as a result (Menon, 2000). Others shared similar stories they had heard or experienced. Eventually, one poster said they would send the diner $0.79 with a (nice) letter. Other members liked this idea and together, the group sent letters and contacted the local news station that aired the original story. The presiding judge decided the woman’s 17 days in jail was adequate punishment and ordered her release. SCHIZOPH considered this a victory. In both cases, online organization led to offline advocacy.

Alberici and Milesi (2013) utilized two offline contexts—meetings and an event—to recruit activists to complete questionnaires on various political outcomes. In the surveys of members of these two contexts, online discussions in attendees’ own online communities were found to moderate the predictive effect of politicized identity. Collective action intention was significantly predicted by politicized identity only when participants reported a higher frequency of online discussion. Across contexts, when participants reported higher levels of online discussion, anger did not predict collective action intention. Instead, collective efficacy predicted collective action and fostered collective action intention. Morality supported collective action intention. However, for participants who reported lower levels of online discussion, only anger predicted collective action intention. These results suggest high levels of online interaction can moderate other variables’ influence on collective action intention.

One might suggest organization and communication among online communities and coalitions can improve one’s ability to engage in effective advocacy. One study, however, suggests there are barriers and facilitators to such effectiveness (Kornbluh et al., 2016). In this study, high school students in three classrooms in three different schools practicing youth-led social change initiatives participated in a Facebook group. Being in the Facebook group inspired students to take action in their own projects and enabled them to receive ideas from other students. Some students were able to name specific instances where seeing another student’s post gave them an idea for what they could do with their own projects. In addition to these facilitators, there were barriers to diffusion, specifically a lack of instructor engagement and in-class discussion about the Facebook group, and the fact the students were all engaging in activism in different topics. From these findings, we may suggest online communities engaged in advocacy dedicate time to reflection and focus on similar topics to facilitate diffusion of ideas.

The internet allows engaged political citizens to organize on issues important to them. While we only found four articles, all highlight the complexity of engaging in advocacy. Most event organizing happened online, while the actions resulting from these efforts happened primarily offline. It may be our political processes have not yet advanced to a point where we can truly engage in them from our laptops and mobile phones as impactfully as we would like, but it may also be research has not caught up to the merging of offline and online worlds.

In these articles, advocates utilized a variety of online and offline tools in order to create change. The internet was used to share news, action plans, and results of different actions. Given the ease with which community members alternated between online and offline contexts, an argument can be made we should not distinguish sharply between online and offline advocacy, and instead see online tools as just that: tools. Whether online or offline, it is still advocacy.

Discussion

The discussion reflects on and integrates the studies of this literature review in the context of the four major categories identified in addressing the research question regarding the content of the articles about online communities. These four are: community building and sense of community, community support, norms and attitudes of online communities, and advocacy. Implications for future research and action in each category are considered in these four sections and broader implications for research and action are presented in their own section. In consideration of the first research question regarding the number of articles published, as Figure 1 illustrates, community psychologists’ interest in online communities has remained low (23) in the past two decades, although the findings of the studies that have been done have been illuminating. Many studies drew parallels or comparisons with offline spaces. For example, some articles explored questions like how online sense of community may map on to or influence offline sense of community or how online communities may provide social support. Other studies have examined how norms and attitudes we have seen in offline contexts might be recreated in specific online contexts and how online advocacy might influence offline advocacy. Lastly, we have also seen some suggestions around synergy between online and offline worlds, to the extent it may make more sense to work towards understanding their various combinations rather than attempting to understand them in isolation. This section will summarize major patterns and suggest further exploration for our field to be informed by, and thus potentially inform online communities.

Community Building and Sense of Community

Community psychology research has indicated it is possible to create a sense of community via online communities, although there is disagreement about what this might look like. Some applications of social media are likely to foster networked individualism rather than a true sense of community (Reich, 2010). However, it remains to be seen whether and under what conditions social networks can host true virtual communities, networks of individuals, or some combination of both over time. When a community assembles for a more unified purpose, sense of community does appear to be possible and even likely (O’Connor et al., 2015). Further, Niland and colleagues (2015) suggest online connections are just as important as offline connections. There is no doubt the internet is increasingly important to interacting with others (Li et al., 2014; Loomis & Friesen, 2011; O’Connor et al., 2015; Reich et al., 2014). In fact, lack of access to the internet can have a negative effect on individuals (Vázquez et al., 2015).

Yet, there is little curiosity in community psychology literature about whether sense of community manifests differently in online and hybrid communities. Researchers disagree on how best to measure sense of community in traditional face-to-face contexts (Nowell & Boyd, 2010; McMillan, 2011; Stevens, Jason, Olson, & Legler, 2012; Jason, Stevens, & Ram, 2015). If we accept sense of community is contingent on ecology, then we must concede a separate or elaborated measurement framework might apply to virtual and hybrid communities compared to in person communities. For example, in a study of 97 online-originated and 80 offline-originated online communities expanding on McMillan and Chavis’ (1986) sense of community construct, Koh and Kim (2003) found community leaders’ enthusiasm and perceived similarity amongst members impacted members’ sense of belonging more for online- than offline-originated communities. Additionally, frequency of offline activities impacted members’ sense of influence over the community more for online- than for offline-originated hybrid communities.

As in face-to face contexts, not all online gatherings are communities. As a result, it could be argued that some studies in community psychology journals, while uncovering valuable knowledge about communication online, are not assessing community phenomena. Two such examples include Wood’s (2018) thematic analysis of news site comment sections and August and Liu’s (2018) thematic and discourse analysis of YouTube comments. Wood’s (2018) analysis applying Bandura’s moral disengagement theory to comments on three news articles about anthropogenic climate change is focused on individual behavior. August and Liu (2014) note that of the 900 YouTube comments they examined in their discourse analysis, only 120 of these comments were replied to, with the modal conversation length being one comment and one reply. While August and Liu (2014) sought to learn if Gricean norms of cooperative conversation applied to race talk in YouTube comments, they add commentary on the general, “thin-sliced, anonymous/shallow” nature of these comment sections. In this way, communication research helps to explore the boundaries of the definition of community. However, direct investigation is required to understand the differences between online and face-to-face communities and is a quicker way to understand the landscape of the ways we associate online.

One area where virtual sense of community is more reminiscent of McMillan and Chavis’ conception of sense of community is the importance of behavioral norms and social support (Blanchard, 2008). Observing and posting supportive messages were related to increased perception of behavioral norms around support, which in turn was related to an increased sense of community. Additionally, supportive communication members received or sent through private messages directly increased sense of community. For these reasons, Blanchard (2008) suggested social norms mediate the relationship between members’ well-documented need to be identified on the one hand and have a sense of community on the other. Practitioners may be able to help community members align their social norms to the purpose of the community and help community leaders develop strategies to increase perceptions of social support within their communities.

More research is needed to hone our understanding of sense of community and online communities generally, which can affect how researchers and practitioners’ interface with online and hybrid communities. For instance, how does member turnover affect online communities, and what are the patterns of membership? To what extent and in what ways are new members recruited or discouraged? What is done to sustain or discourage participants’ interest? How do perceptions of a community affect how community members interact with outsiders? For example, researchers and practitioners seeking to gain entrée into gaming communities may need to pay special attention to community members’ perceptions of how others see them. Much of the psychological research on gaming in the 1990s and 2000s seemed focused on demonstrating video games cause violence (Steltenpohl, Reed, & Keys, 2018). To understand these processes, we need to hear from researchers and practitioners alike on which strategies work and which fail, and how well research findings replicate in real-world application. Then community psychologists will have a sound basis for assisting online communities in developing a stronger community and therewith a stronger sense of community.

Community Support

Research reviewed here suggests community psychologists can use the internet to help members of communities, particularly those with members marginalized by others, provide support to one another (Barrera et al., 2002; Bliuc, Doan, & Best, 2018; Chong et al., 2015; Dunham et al., 1998; Dyer et al., 2010; Obst & Stafurik, 2010). Understanding how community support may look similar and different across communities may be helpful as communities and community psychologists attempt to build support networks for individuals who are socially isolated for a variety of reasons. Examples may include, but are not limited to, being a member of a very specific community (e.g. those who have been diagnosed with orphan diseases), living in a sparsely populated area (e.g. rural settings), or being a member of a stigmatized and targeted community (e.g. identifying as trans in a very conservative area).

Research on online communities can also enhance the social support literature. As we have seen, online mutual help groups have been in part successful. Interestingly, the online social support literature features more successes than the online sense of community literature. This may be because social support is a more concrete concept, with researchers generally agreeing on the definition of social support (Saegert & Carpiano, 2017) compared to the ambivalence surrounding the definition of sense of community (Abfalter et al., 2012; Blanchard, 2008; Koh & Kim, 2003; McMillan, 2011; Nowell & Boyd, 2010; Stevens, Jason, Olson, & Legler, 2011; Jason, Stevens, & Ram, 2015). The social support literature is especially encouraging, however, as it shows face-to-face support, even among strangers, is possible.

We may ask how we can design interventions to turn strangers into supporters. Additionally, how much of an effect can we reasonably expect online communities to have in practice? Barrera et al. (2002) suggest social integration may not be affected by online mutual help groups but may alter perceptions of support. If true, this leads to other questions. How long does it take for positive outcomes of online communities to manifest, if ever? How might we integrate online support groups into already existing interventions? How does online social support affect other activities, such as engagement in advocacy?

Norms and Attitudes

We can also study how online communities’ norms and attitudes affect their activities like advocacy work. Future research may focus on when digital efforts are helpful or harmful to advocacy efforts, and what is needed to have a successful digital advocacy campaign. Importantly, we can ask how we can moderate online advocacy campaigns through the building of community norms and attitudes. For example, the participants in the 79 Cent Campaign influenced each other’s letters by highlighting the value of being courteous during the discussion on the listserv (Menon, 2000).

It would behoove community psychologists to look beyond our field to understand how advocacy and norms may be affected by online technologies. For example, fan communities have used online technologies to advocate for their interests for years (Bennett, 2012; Dimitrov, 2008; Earl & Kimport, 2009). Researchers have studied online communities such as “Black Twitter” (Brock, 2012; Florini, 2014; Sharma, 2013) and “Academic Twitter” (Letierce, Passant, Breslin, & Decker, 2010; Stewart, 2015; Stewart, 2016) to explore how specific groups of people communicate and how these strategies may change over time.

Advocacy

Advocacy efforts can be developed and implemented online (Brady et al., 2015; Menon, 2000) and online advocacy behaviors might affect offline efforts (Alberici & Milesi, 2013). While online communities can become echo chambers, estimates of online ideological segregation may be overestimated (Barberá, Jost, Nagler, Tucker, & Bonneau, 2015). Internet contact, if used well, could foster action intention, although there are potential barriers to the acceptance of new ideas and strategies (Alberici & Milesi, 2013). More research is needed on best practices and ways community groups might focus efforts using social media and project management resources like Basecamp and Slack. Beyond capturing online community members’ advocacy efforts, it would be instructive to investigate the degree to which these communities do or do not facilitate empowerment for their members.

Empowerment develops in progressive stages, contingent on a supportive external response from the environment with which a community interacts (Bothne & Keys, 2016; Keys, 1993). From the studies discussed above, there is reason to believe online settings provide supportive responses through opportunities to participate (the first stage in Keys’ model), resulting in power within (Keys, 1993). The literature reviewed suggests members are willing to take risks in sharing their experiences with others. This willingness to take risks is essential to the second phase, voice own reality and experience, resulting in power to. However, mentions of themes germane to the subsequent three stages in the Keys model (viz., affirmation/power with, increased choice and impact/power over, dignity efficacy and self-respect/power realized) are less commonly encountered in extant community psychology research. These partial parallels suggest the examination of empowerment in online communities could be a promising area of investigation. Evidence for the impact of online communities on advocacy efforts may portend the uncovering of their positive impact on empowerment.

Additional Opportunities for Research and Action

There are topics worth exploring not yet found in this literature on online communities. Community psychologists are well positioned to explore emerging issues like conflict resolution, justice, resistance to oppression, and restorative justice practices in online settings (Goodman, 2006; Katsh, 2007; Powell, 2015). Community psychologists could also serve important roles in the push against group polarization and extremism (Yardi & Boyd, 2010). Additionally, we might explore members’ views of their identity in light of their online communities. Community psychologists could also study how others see their community through understanding concepts such as metastereotypes (Steltenpohl, Reed, & Keys, 2018) as they relate to online communities. Online strategies may map onto strategies we use for offline conflict resolution, or we may be able to find unique ways to lessen conflict using technologies as they develop, such as using virtual reality to build empathy (Robertson, 2016).

As noted above, most of the articles were descriptive in nature with only a few involving research designs amenable to sophisticated quantitative or qualitative analysis. The relative lack of methodological sophistication in most of the articles reviewed speaks to the nascent nature of research concerning online communities in community psychology. Future work can utilize qualitative methods such as online discourse analysis to probe the meaning of online communities and their dynamics for the users and quantitative methods like highly structured surveys to examine specific issues of interest.

Theories popular in community psychology may also be beneficial to the studying of online communities, especially as researchers in the field of “cyberpsychology” consider their research’s own theoretical foundations (or lack thereof) (Orben, 2018). Bronfenbrenner’s (1977) ecological systems framework could be used to understand online and hybrid communities. For example, it may help us to understand how policy can affect how people use the internet. Recently, the United States Federal Communications Commission repealed net neutrality, which protected users from internet service providers blocking access to certain websites or offering paid prioritization plans (Shepardson, 2018). This repeal of net neutrality has the potential to massively affect how people use the internet, if the courts side with the FCC.

Further, there is what some consider a “moral panic” surrounding screen time, leading to organizations releasing conflicting guidelines. For example, the World Health Organization (2019) makes cut-off recommendations for children under five but does not outline evidence for this recommendation and acknowledges a research gap. However, the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (2018) explicitly states there is no strong evidence for a threshold and does not make a cut-off recommendation at all. Indeed, recent pre-registered research suggests little evidence for meaningfully negative associations between screen time and adolescent well-being (Orben & Przybylski, 2019). Community psychologists working in research and practice settings with children and families should be aware of current stereotypes about media’s effects on well-being and the direction of current research.

Lastly, most of these studies focus on younger adults. We know older adults often differ from younger adults on dimensions like processing capacity, judgment, knowledge, emotion regulation, attention to emotion, affective perspective taking, and the interpretation of ambiguous scenarios (Carstensen & Mikels, 2005). We might reasonably think there are differences in how older adults use the internet and when they may find the internet relevant or irrelevant to their social goals. Some research suggests older adults who use social media have a strong preference for connecting with family (Swayne, 2016). There may be differences in usage of and feelings toward the internet between individuals who grew up with the internet and those for whom the internet came into existence later in life. Given concerns about loneliness among older adults (Zhong, Chen, Tu, & Conwell, 2017), could online communities be one form of intervention for older adults without stable social networks?

There are other questions we may be able to tap into, given time and a concerted effort to disseminate our current practices with online communities, and make an intentional effort to include online communities in our research and practice. The potential here is virtually boundless.

Conclusion

Given the internet is an increasingly important part of people’s lives and unlikely to have less influence as time goes on, we have a responsibility as community psychologists to explore the types of online communities and activities with which people can engage. Online communities have much to offer community psychology in terms of theory, research, and action. By continuing to explore online and hybrid communities, drawing on interdisciplinary work as we build the literature within our field, we can move toward understanding this increasingly important aspect of the future. Further, we can apply what we know about online communities--through community psychology and other fields--to create contexts allowing community members to be empowered to advocate for themselves and issues they care about.

Of concern is the lack of conscious curation of research regarding online and hybrid communities, especially insofar as it can inform social action. These communities fall within community psychology’s domain of interest and should be a prime future focus. When our approaches and foci do not include a globally prevailing, volatile, and massively influential modality for creating and sustaining community, these approaches and foci must change. In order for the field to be relevant to the way humans take part in community in the following decades, we need to conscientiously coordinate research effort with a mind towards our future. As the late Oliver Wendall Holmes Jr. (1884) once said, “I think that, as life is action and passion, it is required ... that [people] should share the passion and action of [their] time at peril of being judged not to have lived.”

References

Abfalter, D., Zaglia, M.E., & Mueller, J. (2012). Sense of virtual community: A follow up on its measurement. Computers in Human Behavior, 28, 400–404.

Alberici, A.I., & Milesi, P. (2013). The influence of the internet on the psychosocial predictors of collective action. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 23, 373–388.

Anderson, M., & Jiang, J. (2019). Teens, Social Media & Technology 2018. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2018/05/31/teens-social-media-technology-2018/

Arcidiacono, C., Procentese, F., & Baldi, S. (2010). Participatory planning and community development: An e-learning training program. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community, 38, 70–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/10852350903393475

August, C., & Liu, J.H. (2015). The medium shapes the message: McLuhan and Grice revisited in Race Talk Online. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 25, 232–248.

Barberá, P., Jost, J.T., Nagler, J., Tucker, J.A., & Bonneau, R. (2015). Tweeting from left to right: Is online political communication more than an echo chamber? Psychological Science, 26, 1531–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797615594620

Barrera, M., Glasgow, R.E., McKay, H.G., Boles, S.M., & Feil, E.G. (2002). Do internet-based support interventions change perceptions of social support?: An experimental trial of approaches for supporting diabetes self-management. American Journal of Community Psychology, 30, 637–654. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1016369114780

Bennett, L. (2011). Fan activism for social mobilization: A critical review of the literature. Transformative Works and Cultures, 10. http://journal.transformativeworks.org/index.php/twc/article/view/346/277

Blanchard, A.L. (2008). Testing a model of sense of virtual community. Computers in Human Behavior, 24, 2107-2123.

Bliuc, A.M., Doan, T.N., & Best, D. (2019). Sober social networks: The role of online support groups in recovery from alcohol addiction. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 29(2), 121-132.

Bond, M.A., Serrano-García, I., & Keys, C.B. (2017). APA Handbook of Community Psychology. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association.

Bothne, N. & Keys, C. (2016). An examination of human rights and community empowerment. Presentation at the 6th International Conference of Community Psychology. Durban, South Africa.

Brady, S.R., Young, J.A., & McLeod, D.A. (2015). Utilizing digital advocacy in community organizing: Lessons learned from organizing in virtual spaces to promote worker rights and economic justice. Journal of Community Practice, 23, 255–273.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101.

Brock, A. (2012). From the blackhand side: Twitter as a cultural conversation. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 56, 529-549.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1977). Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American Psychologist, 32, 513.

Brunson, L., & Valentine, D. (2010). Using online tools to connect, collaborate and practice. Global Journal of Community Psychology Practice, 1, 1–8.

Carstensen, L.L., & Mikels, J.A. (2005). At the intersection of emotion and cognition: Aging and the positivity effect. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14, 117–121.

Castells, M. (2001). The internet galaxy: Reflections on the internet, business, and society. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Chong, E.S.K., Zhang, Y., Mak, W.W.S., & Pang, I.H.Y. (2015). Social media as social capital of LGB individuals in Hong Kong: Its relations with group membership, stigma, and mental well-being. American Journal of Community Psychology, 55, 228–238.

Cole, H., & Griffiths, M.D. (2007). Social interactions in massively multiplayer online role-playing gamers. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 10, 575-583.

Dimitrov, R. (2008). Gender violence, fan activism and public relations in sport: The case of “Footy Fans Against Sexual Assault”. Public Relations Review, 34, 90-98. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0363811108000349

Dunham, P., Hurshman, A., Litwin, E., Gusella, J., Ellsworth, C., & Dodd, P.D. (1998). Computer-mediated social support: Single young mothers as a model system. American Journal of Community Psychology, 26, 281–306.

Dyer, J., Costello, L., & Martin, P. (2010). Social support online: Benefits and barriers to participation in an internet support group for heart patients. The Australian Community Psychologist, 22, 48–67.

Earl, J., & Kimport, K. (2009). Movement societies and digital protest: Fan activism and other nonpolitical protest online. Sociological Theory, 27, 220-243. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/j.1467-9558.2009.01346.x

Figueroa Sarriera, H.J., & González Hilario, B. (2017). Emerging technologies: Challenges and opportunities for community psychology. In M. A. Bond, C. B. Keys, & I. Serrano-García (Eds.), APA Handbook of Community Psychology. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association.

Florini, S. (2014). Tweets, tweeps, and signifyin’: Communication and cultural performance on “Black Twitter”. Television & New Media, 15, 223-237. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/1527476413480247

Goodman, J.W. (2006). The advantages and disadvantages of online dispute resolution: An assessment of cyber-media. Journal of Internet Law, 9, 10–16.

Grant, M. J., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 26(2), 91-108. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

Hammond, M. (2017). What is an online community? A new definition based around commitment, connection, reciprocity, interaction, agency, and consequences. International Journal of Web Based Communities, 13(1). 118-136.

Holmes, O.W. (1884). Dead, yet living: An address delivered at Keene, NH, Memorial Day, May 30, 1884. Boston, MA: Ginn, Heath, & Company.

Jason, L.A., Stevens, E., & Ram, D. (2015). Development of a three-factor psychological sense of community scale. Journal of Community Psychology, 43, 973–985.

Jimenez, T.R., Sánchez, B., McMahon, S.D., & Viola, J. (2016). A vision for the future of community psychology education and training. American Journal of Community Psychology, 58, 339–347. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12079

Katsh, E. (2007). Online dispute resolution: Some implications for the emergence of law in cyberspace. International Review of Law, Computers & Technology, 21, 97–107.

Keys, C. (1993). Empowerment through advocacy. Presentation at the Annual International Conference of the Young Adult Institute, New York, NY.

Klaw, E., Dearmin Huebsch, P., & Humphreys, K. (2000). Communication patterns in an on-line mutual help group for problem drinkers. Journal of Community Psychology, 28, 535–546.

Koh, J., & Kim, Y.G. (2003). Sense of virtual community: A conceptual framework and empirical validation. International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 8, 75–93.

Kornbluh, M., Watling Neal, J., & Ozer, E.J. (2016). Scaling-up youth-led social justice efforts through an online school-based social network. American Journal of Community Psychology, 57, 266–79. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12042

Krause, M., & Montenegro, C.R. (2017). Community as a multifaceted concept. In M. A. Bond, C. B. Keys, & I. Serrano-García (Eds.), APA Handbook of Community Psychology. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association.

Letierce, J., Passant, A., Breslin, J.G., & Decker, S. (2010). Using Twitter during an academic conference: The# iswc2009 use-case. In ICWSM.

Lazarus, S., Seedat, M., & Naidoo, T. (2017). Community building: Challenges of constructing community. In M. A. Bond, C. B. Keys, & I. Serrano-García (Eds.), APA Handbook of Community Psychology. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association.

Lenzi, M., Vieno, A., Altoe, G., Scacchi, L., Perkins, D.D., Zukauskiene, R., & Santinello, M. (2015). Can Facebook informational use foster adolescent civic engagement? American Journal of Community Psychology, 55, 444–454. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-015-9723-1

Li, W.W., Hodgetts, D., & Sonn, C. (2014). Multiple senses of community among older Chinese migrants to New Zealand. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 24, 26–36. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.2174

Loomis, C., & Friesen, D. (2011). Where in the world is my community? It is online and around the world according to missionary kids. Journal of Community Psychology Practice, 2, 31-40.

Madara, E.J. (1997). The mutual-aid self-help online revolution. Social Policy, 27, 20–26.

Majaski, C. (2015). Haters call for Star Wars boycott because new movie has too much diversity. Digital Trends. http://www.digitaltrends.com/social-media/star-wars-boycott/

McMillan, D.W. (2011). Sense of community, a theory not a value: A response to Nowell and Boyd. Journal of Community Psychology, 39, 507-519.

McMillan, D.W., & Chavis, D.M. (1986). Sense of community: A definition and theory. Journal of Community Psychology, 14, 6–23.

Menon, G.M. (2000). The 79-Cent Campaign. Journal of Community Practice, 8, 73–81.

Niland, P., Lyons, A.C., Goodwin, I., & Hutton, F. (2015). Friendship work on Facebook: Young adults’ understandings and practices of friendship. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 25, 123–137. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.2201

Nic Giolla Easpaig, B. (2018). An exploratory study of sexism in online gaming communities: Mapping contested digital terrain. Community Psychology in Global Perspective, 4(2), 119-135.

Nip, J. (2004). The relationship between online and offline communities: The case of the Queer Sisters. Media, Culture, and Society, 26, 409–429.

Nowell, B., & Boyd, N. (2010). Viewing community as responsibility as well as resource: Deconstructing the theoretical roots of psychological sense of community. Journal of Community Psychology, 38, 828–841. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.20398

O’Connor, E.L., Longman, H., White, K.M., & Obst, P.L. (2015). Sense of community, social identity and social support among players of Massively Multiplayer Online Games (MMOGs): A qualitative analysis. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 25, 459–473. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.2224

Obst, P., & Stafurik, J. (2010). Online we are all able bodied: Online psychological sense of community and social support found through membership of disability-specific websites promotes well-being for people living with a physical disability. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 20, 525–531. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.1067

Orben, A. (2018). Cyberpsychology: A field lacking theoretical foundations. PsyPAG Quarterly, 107, 12-14. http://www.psypag.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/PsyPag-107-web.pdf

Orben, A., & Przybylski, A.K. (2018). Screens, teens and psychological well-being: Evidence from three time-use diary studies. Psychological Science, 1-15. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0956797619830329

Pew Research Center. (2019). Internet/broadband fact sheet. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/internet-broadband/

Pita, M.S. (2012). Construction of a Portuguese online forum for mutual help. Global Journal of Community Psychology Practice, 3, 1-2.

Powell, A. (2015). Seeking rape justice: Formal and informal responses to sexual violence through technosocial counter-publics. Theoretical Criminology, 19, 571–588.

Reich, S.M. (2010). Adolescents’ sense of community on Myspace and Facebook: A mixed-methods approach. Journal of Community Psychology, 38, 688–705.

Reich, S.M., Black, R.W., & Korobkova, K. (2014). Connections and communities in virtual worlds designed for children. Journal of Community Psychology, 42, 255–267.

Riley, S., Rodham, K., & Gavin, J. (2009). Doing weight: Pro-ana and recovery identities in cyberspace. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 19, 348–359.

Robertson, A. (2016). The UN wants to see how far VR empathy will go. The Verge. http://www.theverge.com/2016/9/19/12933874/unvr-clouds-over-sidra-film-app-launch

Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (2018). The health impacts of screen time - A guide for clinicians and parents. https://www.rcpch.ac.uk/resources/health-impacts-screen-time-guide-clinicians-parents

Saegert, S., & Carpiano, R.M. (2017). Social support and social capital: A theoretical synthesis using community psychology and community sociology approaches. In M. A. Bond, C. B. Keys, & I. Serrano-García (Eds.), APA Handbook of Community Psychology. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association.

Salem, D.A., Bogat, G.A., & Reid, C. (1997). Mutual help goes on-line. Journal of Community Psychology, 25, 189–207.

Seymour, W.S. (2001). In the flesh or online? Exploring qualitative research methodologies. Qualitative Research, 1, 147-168.

Sharma, S. (2013). Black Twitter?: Racial hashtags, networks and contagion. New Formations: A Journal of Culture/Theory/Politics, 78, 46-64.

Shepardson, D. (2018). U.S. defends FCC's repeal of net neutrality rules. Forbes. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-internet/u-s-defends-fccs-repeal-of-net-neutrality-rules-idUSKCN1MM242

Shirky, C. (2009). Here comes everybody: The power of organizing without organizations. London, UK: Penguin.

Shull, C.C., & Berkowitz, B. (2005). Community building with technology: The development of collaborative community technology initiatives in a mid-size city. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community, 29, 29–41. https://doi.org/10.1300/J005v29n01_03

Steltenpohl, C.N., Reed, J., & Keys, C.B. (2018). Do others understand us? Fighting game community member perceptions of others’ views of the FGC. Global Journal of Community Psychology Practice, 9, 1-21.

Stevens, E.B., Jason, L.A., Olson, B., & Legler, R. (2012). Sense of community among individuals in substance abuse recovery. Journal of Groups in Addiction & Recovery, 7, 15-28.

Stewart, B. (2016). Collapsed publics: Orality, literacy, and vulnerability in academic Twitter. Journal of Applied Social Theory, 1. http://socialtheoryapplied.com/journal/jast/article/view/33/9

Stewart, B. (2015). Open to influence: What counts as academic influence in scholarly networked Twitter participation. Learning, Media and Technology, 40, 287-309. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/17439884.2015.1015547

Swayne, M. (2016). The lure of grandkids draws seniors to social media. Research Matters. http://researchmatters.psu.edu/2016/04/12/the-lure-of-grandkids-draws-seniors-to-social-media/

Tebes, J.K. (2016). Reflections on the future of community psychology from the generations after Swampscott: A commentary and introduction to the special issue. American Journal of Community Psychology, 58, 229–238. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12110

Vázquez, J.J., Panadero, S., Martín, R., & del Val Diaz-Pescador, M. (2015). Access to new information and communication technologies among homeless people in Madrid (Spain). Journal of Community Psychology, 43, 338–347. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.21682

Wesch, M. (2009). From knowledgeable to knowledge-able: Learning in new media environments. Academic Commons, 4–9.

Whittaker, L., & Gillespie, A. (2013). Social networking sites: Mediating the self and its communities. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 23, 492–504. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.2148

Woods, R., Coen, S., & Fernández, A. (2018). Moral (dis)engagement with anthropogenic climate change in online comments on newspaper articles. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 28(4), 244-257.

World Health Organization (2019). WHO guidelines on physical activity, sedentary behavior, and sleep for children under 5 years of age. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/311664/9789241550536-eng.pdf

Yardi, S., & Boyd, D. (2010). Dynamic debates: An analysis of group polarization over time on Twitter. Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society, 30, 316–327.

Zhong, B.L., Chen, S.L., Tu, X., & Conwell, Y. (2017). Loneliness and cognitive function in older adults: Findings from the Chinese longitudinal healthy longevity survey. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 72, 120-128.

Author Disclosure Statement

None of the authors have any commercial associations or financial interests that might create a conflict of interest in connection with this manuscript

Figure1. Historical publishing of community psychology articles on online communities |

Table 1.Articles included in Review (Part 1) |

Table 1.Articles included in Review (Part 2) |

Crystal N. Steltenpohl, Jordan Reed, and Christopher B. Keys

Crystal N. Steltenpohl, Jordan Reed, and Christopher B. Keys

Crystal N. Steltenpohl, is an assistant professor of psychology and founder of the Online Technologies Lab at the University of Southern Indiana. As a scholar, gamer, and participant in online worlds, her major research interests revolve around how we interact with various technologies, especially those that house online communities.

Jordan Reed, is a graduate student in the community psychology program at DePaul University. He is a founding member of the Online Technologies Lab, receiving a SCRA Community Mini-Grant with Dr. Steltenpohl. He examines metastereotypes and community prototypes held by members of the fighting game community.

Christopher Keys, is professor emeritus and former chair of the psychology departments at the University of Illinois at Chicago and DePaul University. He was also the founding associate dean for research and faculty development in the College of Science and Health at DePaul. A fellow of APA, MPA, and SCRA, Chris served as President of the Society for Community Research and Action.

agregar comentario