Sexual assault on college campuses is a national issue, with a recent report from the White House estimating that 20% of women will experience a sexual assault during college. Students at Wichita State University formed a campus organization to bring visibility to both community psychology and address this important problem. The Community Psychology Association is comprised of both graduate and undergraduate students, and members utilized three community psychology competencies: ecological perspectives, information dissemination/building public awareness, and community organizing and community advocacy in their work to improve resources and campus support for this issue. Community Psychology Association members utilized focus groups with campus students, faculty, and staff to facilitate discussions on sexual assault, campus safety, and university and administrative accountability. Content analysis revealed multiple themes that were used to generate a larger campus discussion and promote change in campus policies. As a result of these activities, major changes occurred at Wichita State, including data driven programming for interventions regarding sexual assault, changes in leadership in the offices of Title IX and Student Affairs, support for a CDC grant, and overall increased organizational awareness for sexual assault survivors. This study highlights the importance of applying community psychology principles and concepts to research and action to ultimately have a positive and tangible impact on the local community.

Download the PDF version for the full article, including all tables, figures, and appendices

Context for Using the Competencies with Campus Sexual Assault

The White House recently made headlines by reporting that approximately one out of five women would experience a sexual assault during their attendance at a university, and the Association of American Universities published the results of their study showing a range of incidence between 13% and 30% (White House Task Force to Protect Students From Sexual Assault, 2014; Cantor, et.al., 2015). The Community Psychology Association at Wichita State University (WSU) recognized the need for an examination of this issue on their campus after a sexual assault occurred in a new dormitory and students and faculty were dissatisfied with the University’s response. Three community psychology competencies guided the Community Psychology Association in an effort to address sexual assault on WSU’s campus. The competencies most relevant to the issue were Ecological Perspectives, Information Dissemination and Building Public Awareness, and Community Organizing and Community Advocacy. This article discusses community psychology students’ engagement with research and practice regarding sexual assault prevention and the resulting positive impact on the university community.

Ecological Perspectives

Wichita State University[1] (WSU) is situated in an urban setting within the city of Wichita, Kansas. Its student body is split between a majority of commuters (those students who live off campus) and a smaller percentage of students living in on-campus housing. Importantly, that dynamic began rapidly changing in the fall of 2014. With the construction and occupation of new dorms on campus, the residential student population more than doubled literally overnight. Neither the situation of a college campus within an urban setting, nor the large proportion of commuter students make the ecology of WSU unique. What does make Wichita State unique is the rapid expansion of a residential population, a lack of relationship with urban- and community-based sexual assault services, and a lack of experience with sexual assault (due to a relatively small residential student population). This ecological context was important to both the assault that happened in the fall of 2014 (Miller, 2014; Sunflower, 2014), the dissatisfying university response, and a growing realization that the culture at Wichita State needed to be examined in order to improve campus response to sexual assault.

Many urban universities work with the communities in which they are located, establishing relationships with organizations specializing in assault or trauma to provide consistent information and support for those who survive an assault. For example, DePaul University in Chicago, Illinois, provides information about the Chicago Rape Crisis Hotline and also works with the local YWCA to train faculty and staff to be certified rape crisis workers (Sexual & Relationship Violence Prevention, 2016). Wichita State has not cultivated the same relationships with community partners. The Wichita Area Sexual Assault Center (WASAC) is a leader in crisis intervention in Wichita, and yet the WSU website provides no information about the services WASAC can provide. The university has essentially tried to handle issues related to sexual assault within the confines of its own internal protocols and campus safety department.

The ecological context of sexual assault at WSU was unique due to:

This unique context made ecology an important consideration when thinking about how to address this issue. By taking an ecological perspective and making the different layers of context an essential component in the approach to studying the issue, the Community Psychology Association – a student-led campus organization – was able to move the conversation away from victim blaming and individual action, instead focusing on a system that was not equipped to prevent assault from occurring. The study and ultimately the advocacy was informed by this ecological context and considered foundational to both how data were to be collected and how they should be analyzed and framed in dissemination.

Information Dissemination/Building Public Awareness

The crux of information dissemination and building public awareness is “giving psychology away” through engaging diverse groups in dialogue and consultation, empowering community members, and tailoring the communication of results to stakeholders to inform their action (Dalton & Wolfe, 2012). In the work undertaken at Wichita State, multiple stakeholder groups were consulted and involved in the research and action that took place. Viewing the campus as a community with a specific ecology necessitated collaboration in the process of identifying how, where, and what to ask community members. This was done with the aim, expectation, and purpose of building awareness about the issue of sexual assault on campus, convincing the community that the problem was one that needed more direct intervention and prevention efforts. Additionally, the Community Psychology Association focused on university officials, student stakeholders, and other members of the community to have the greatest impact with dissemination of results.

Community Organizing and Community Advocacy

The competency of Community Organizing and Community Advocacy heavily influenced the approach to addressing sexual assault on Wichita State’s campus. Marti-Costa and Serrano-Garcia (1983) have argued “needs assessment may be utilized as a central method to facilitate the modification of social systems so they become more responsive to human needs” (p. 75). The Community Psychology Association modeled their approach to understanding the culture of sexual assault at WSU on this idea, with the strategy of using this process of learning the needs of the campus community to also mobilize constituents and activate change. They actively recruited undergraduate and graduate students to fully engage in the process of research and action focusing on sexual assault on campus. Research efforts began as the Community Psychology Association utilized this approach with stakeholder focus groups to generate qualitative data that would be linked to advocacy efforts and would describe the ecology of the campus from the perspective of individuals living in that environment. Additionally, these data provided a foundation to shift discussions away from traditional victim blaming and focus on systemic issues that would be targeted for change.

The action phase involved reaching out to the Wichita Area Sexual Assault Center (WASAC) for their experience and expertise, which led to engaging with campus stakeholders including Campus Safety, the Counseling and Testing Center, the office of the Vice President of Student Affairs, the Student Government Association, the university Title IX coordinators, the office of Housing and Residence Life, Greek Life, and other campus entities. The organizing activities expanded the reach of advocacy efforts so that voices from this bottom-up work could not be immediately dismissed by university decision makers who used top-down procedures when developing and enforcing policy. Community psychology principles and these competencies were embedded in this process and helped facilitate this transition from research to action, enabling the Community Psychology Association to have a meaningful and positive impact on the Wichita State campus community through the practice of community psychology.

Methods

The Community Psychology Association

The Community Psychology Association was developed as a local chapter of the Society for Community Research and Action by graduate students who had a desire to bring visibility to Community Psychology, its competencies, and practices in applied settings. Another goal of the association was to introduce undergraduates to the field and engage them in meaningful research and practice around relevant topics at their university. Over the course of designing and implementing this project, undergraduates were directly involved in the research and practice and had the opportunity to receive training in focus group moderation and other advocacy activities.

Focus Group Participants

Participants in the focus groups were students and faculty at the university and were required to be at least 18 years of age and English speaking. There were no other exclusion criteria. Participation was voluntary, and recruitment used fliers, emails, and tables set up at the student center during high traffic times. Participants received a $5 gift card at the conclusion of the study. Two-person teams facilitated separate focus groups for students and faculty and were gender-specific to the corresponding genders of the groups. Student groups consisted of a male only, female only, and a mixed gender group. Lack of response from male faculty and staff resulted in a faculty group of female participants only.

Focus Group Script

A packet for each team of facilitators helped keep consistency between focus group conversations among participants. Participants had a coordinating packet that allowed them to write down their responses and help gather their thoughts before responding in a discussion to the group. Questions included defining sexual assault, what information would be useful in incident reporting, responding to a friend that had been sexually assaulted in a hypothetical scenario, estimating prevalence, law enforcement as a resource, and identifying safe and unsafe areas on campus and the surrounding neighborhoods (for the full discussion guide, please see Appendices A and B). Experienced graduate student facilitators mentored less experienced undergraduate and graduate student facilitators, including an hour-long training session to prepare all who would lead focus groups. An important part of this procedure was the integral participation of the population (i.e., students) who are affected by sexual assault and the policies addressing this issue.

Procedures

Focus groups utilized paired facilitators who each moderated different parts of the discussion. Informed consent was obtained from each participant, and conversations were audio or video recorded for later transcription. Groups were held on campus in the student center as a centrally located and contextually relevant environment. The moderator facilitated discussion through open-ended questions, sometimes assisted by having participants write responses to questions in a handout packet and subsequently discussing written answers with the group. Follow-up questions for clarity and expansion of answers led to more in-depth discussion among group members. Basic demographic information was also collected. The audio or video recording of each group was transcribed for further analysis.

Results

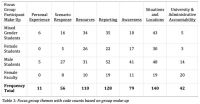

Focus group data were coded and analyzed following a conventional qualitative content analysis approach (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). Each focus group interview was transcribed, and researchers collaboratively determined codes based on the data transcriptions and created a codebook for analysis. The research team used this codebook to organize key statements in transcripts according to these predetermined codes. Coding was understood as a process to understand the overall themes and to recognize trends and patterns that contribute to the interpretation (Boyatzis, 1998). This process included intercoder agreement, by having a second coder in the analysis of each focus group. The coders then convened and developed consensus meanings for each key statement, which ultimately led to seven themes: 1) personal experience, 2) scenario response, 3) resources, 4) reporting, 5) awareness, 6) situations and locations, and 7) university and administrative accountability. The themes and code counts are found in Table 1.

Table 1: Focus group themes with code counts based on group make-up (see PDF version or JPG below article).

Personal Experience

Of the eight themes that emerged from analyzing qualitative data from the focus groups, personal experience was the least mentioned. This theme related to having directly or indirectly experienced a sexual assault, being impacted by an assault, or otherwise witnessing symptoms of trauma in someone close to them. Neither the female-only nor the female-faculty groups mentioned personal experience in their focus groups. Several participants in the mixed-gender student group knew someone who had experienced sexual assault and the affect it had on them as a confidante. These students mentioned that because of this experience, they are more aware of sexual assault occurrence. Male students echoed similar sentiments in terms of preparedness if a friend confided in them. One student noted that because he has been sexually assaulted:

… three times so I feel very prepared… I’ve done extensive counseling on it and so know if someone does something I feel I've been violated, [I'll] absolutely…take it to the police. I feel very prepared to do that.

Yet another male student relayed that safety or perceptions of safety, at least for some people, may be relative to lived experiences:

I come from a country where you can pay someone $10 to kill someone so I'll just walk and if in the neighborhood there's a drug dealer but he says hi, I have no problem with that. Hey to each his own. You know. So like I have a much higher tolerance I guess to what other people might consider dangerous.

Reporting

Reporting referred to the dissemination of sexual assault’s incidence or prevalence, the reporting of procedures or practices, or the lack of reported cases that are campus-specific, college-specific, or across all contexts. All groups mentioned that the reporting on this particular campus needs more attention and transparency, for there have been instances where a sexual assault has happened, and it was “swept under the rug.” Participants in the mixed-gender group mentioned the University of Virginia case earlier in the study year and cases in general where a survivor came forward and the public backlash intensified. A participant described his/her perspective:

I don't think anyone reports it; I mean rape does happen and a lot of times people won't report it because they're afraid they'll be called a liar.

When asked what types of information the university should =shared= with students about an assault, common information included: location, time of day, relationship between the perpetrator and survivor, what happened to both people, and resources that were made available for the survivor. Regardless of what information was shared, participants in all groups agreed that the survivor’s personal information needed to be protected.

This discussion brought up the point of sharing of information with a large group of people. Messages about incidents, resources, and reporting from the university were thought to be potentially helpful if conveyed via social media (e.g., Twitter, Facebook, Instagram). Many students mentioned that they do not watch the news, so even if universities or the general public report information through that medium, the information would not be received. A few male students also noted the viewpoint around reporting on domestic violence might need to be changed as well:

…the domestic incident is not gonna be headline news. In general it's just, ‘Oh it's in their kitchen let's leave it there.’ And frankly I feel like that should be reported on a little more, should be because then, then you know it's there and you know it's wrong for the people who don't know but it's a form of education.

The female faculty and staff group also brought in a different perspective as mandatory reporters, especially when considering students’ cultural and social backgrounds which may prevent or delay someone from reporting. When a student does share an incident with a faculty or staff member, faculty mentioned they would respect the student’s wishes by connecting them with the resources and reporting methods with which the student felt most comfortable. The female student group also provided another possible reason for fewer reports, citing that the severity of an assault may determine whether or not a student will report (e.g., unwanted groping may not warrant a full police report in the student’s mind). All participants noted how emotionally difficult it was to report any sort of assault, regardless of who the survivor was reporting to or the circumstances of the assault.

Awareness

Awareness was described as being able to define sexual assault and recognize instances in which a potential situation could be difficult to interpret (e.g., at a party between classmates). All groups’ definitions were fairly similar, only differing in the key words each chose to focus on. The overarching definition that transcended groups posits that sexual assault includes unwanted touching, sexual behaviors, and comments from one or more individuals to one or more other individuals. For the male student group, the key word was “unwanted,” in that the recipient of such advances felt an invasion of their personal boundaries. In the female student group, the focus was on the individual’s ability to have their own definition. All groups agreed that the general definition is publicized fairly well on campus, but some participants in the female faculty and mixed-gender groups expressed questions about the discussed differentiation between sexual assault and sexual harassment. Challenges with interpreting consent were a topic of conversation as participants described multiple means of communication.

…we have to get away from a culture of just body language getting more into expressing what we want and how we want it…If we can get to the point where we can verbally express our sexual interests without it being awkward or you know a mood killer.

Many participants recognized that it is necessary for the public to steer away from the misconception that sexual assault is from “stranger danger” to promote safer prevention programs. There was some discussion on trying to determine what is consensual and not, for instance, at a party. In these more ambiguous situations, students said they would be hesitant to intervene. As the female faculty and staff group pointed out, however, it will be necessary to not only focus on females’ abilities to prevent an assault, but also to involve males in the efforts as well.

Scenario Responses

Scenario responses described anything involving the identification of, reaction to, or learning about a sexual assault. This is also regarded as the level of preparation or skill participants believed was needed to handle a situation involving sexual assault. During this point in the discussion, faculty and students were able to express how they would handle specific situations regarding sexual assault and address steps they would take if they had been sexually assaulted or a close friend or student (for the faculty members) had experienced it.

In the student focus groups, a common response was that they did not believe they were particularly prepared about what to do in the event a sexual assault occurred. Participants wanted to believe they would be able to take the proper steps, but in some cases, just did not feel as though they would really know unless it really happened.

I don't know, honestly. You don't really know until it happens to you, so. I'd like to think I'd know what to do just because, you know, I have somewhat, you know, awareness about the situation.

Another important aspect to this theme was how to handle a potential situation if it didn’t seem like an appropriate setting to intervene. Students stated that if it was a circumstance such as a house party, where it was a more casual atmosphere and people were likely to know each other, they would feel more comfortable stepping in if they believed a sexual assault was happening; however, if they were out somewhere like a bar, and weren’t sure about the context between two people who were interacting with one another, they would be less inclined to step in and make sure everything was okay.

If it's that case where it's at a party and the-a girl who's totally drunk and can't even walk… yeah, I can recognize it and if I can, I'll stop it and like make sure the girl finds her friends and they can take her home. But, I mean, in any other case… I could probably recognize it but I mean, if it's not in public.

Although many students believed they would be unprepared in a sexual assault situation, many stated they would report the assault and would strongly encourage a friend to do so if they had been assaulted. Despite stating they would contact authorities, some still made sure to reiterate that they would not be totally sure of what they would do unless they had to deal with it in real life.

I would want it to be reported, and if it were my friend then I would definitely report it, if it were me but I think it would be hard just because like everybody else said, you're never, I mean especially in that situation, you don't know how you're going to handle it until you're in that situation.

Faculty members talked a lot about the current events on the university campus that were relevant to the issue, such as the rape in the new dorms, or assaults that occurred on or near campus grounds. Faculty members thought they had noticed a difference in the way their students conducted themselves, but did not see any big changes among their fellow faculty members. One faculty member said that her students did not mention their assaults until long after they happened, but she still made sure to refer them to the Counseling and Testing Center on campus for additional resources.

Resources

Resources were defined as any type of treatment or prevention resource, which included options such as escorting by police to students’ vehicles, information provided by the Counseling and Testing Center, the Wichita Area Sexual Assault Center (WASAC), topics covered in campus orientations, or any other resources students utilize regarding this issue. Students brought up several points regarding the various resources relating to sexual assault prevention. One that was commonly discussed was the police escort system. Some students believed this was an important resource because a perpetrator was far less likely to assault you if there is a police officer present; however, many believed this option was not appropriate to use more than a couple of times per week, if ever. It was viewed as more of a special option to be used when one really felt unsafe, although specific examples of when that may be the case were not discussed in greater detail.

Another option that students spoke about was using a group system when walking to their cars at night. By using their fellow students and friends as a resource, they had safety in numbers and were able to make sure everyone made it to their vehicles safely and did not have to walk alone at any time. Pepper spray was another option that was brought up, with students saying they made sure to have it on them whenever they walked alone at night.

As far as resources provided directly by programs within the university, students mentioned information they had learned during campus orientations; however, the information they received regarding sexual assault seemed to be mostly tied into the issue of alcohol, and a few students made the suggestion that sexual assault be discussed as an issue on its own.

…it shouldn't be more focused on the alcohol point of view but more focused on sexual assault in general. I mean, there's probably more methodical things you could talk about in orientation than they do.

Female faculty members referenced resources such as WASAC and discussed the importance of really trying to understand what would most benefit the particular situation with the student. These participants believed that academic resources were also an important aspect to the process, as they had seen instances where students were more likely to shut down and stop attending classes. It was suggested that there are always ways to improve upon the resources offered to students in these circumstances.

Is there enough resources? I always think you could have more, you can never have enough resources…

University and Administration Accountability

Participants were concerned with how the university responds to a sexual assault report. Across all groups, participants shared that the university can provide more training and resources and can improve reporting measures. Specifically, students wanted to feel confident that the university will ethically and properly investigate all sexual assault reports. Students also wanted to be informed of the university course of action during and following an investigation: “What is the campus and what is the university going to do about it? Like, after the situation.”

Most participants were concerned with the university’s next steps and wanted to be informed of the course of action taken. Focus group participants also wanted to ensure that survivors received counseling and their needs were met. Also, participants wanted to know that due process had occurred. It was unclear for some staff if they were mandatory reporters, and there was some uncertainty regarding university reporting protocol. Similarly, students believed that when an incident was reported, there was not follow-up to explain what happened, and they wanted to know about incidences sooner: “Let us know on the student listserv, and follow-up.”

Prevention and training were central in this discussion on university administration accountability. Staff reported that there was awareness around sexual assault, but more training was needed around sexual harassment. Participants believed the university could invest in more prevention training beyond self-defense training.

I feel like our campus does not necessarily do as much education here as compared to other campuses.

Situations and Locations

Situation and locations referenced physical locations, context, or social situations where sexual assault happens or hypothetically could happen. Perceptions of safe and unsafe areas were also discussed. Participants were aware of the common rape myth that sexual assault perpetrators are mostly strangers; however, participants did not often discuss other known rape myths as being false, particularly in regard to where and how sexual assault incidences can occur.

Many participants reported not feeling safe in surrounding areas of the campus. This was mainly attributed to the reporting of past criminal incidences that have occurred near the campus, with a common reference to a crime that occurred at a nearby park where the victim was sexually assaulted and murdered. Despite this incident occurring over a year ago, the event and impact was a salient topic of discussion.

I mean, it was devastating, and then, hitting close to home because, I no longer live on this side of town, but I grew up on this side of town so we used to play at that park, you know? It was like man, that could have been anybody. I still have friends and family that live around there, so, it-I mean, scary as hell.

Additionally, some believed the news was biased in reporting sexual assaults that transpire in areas that are deemed as unsafe, and participants were aware that sexual assaults could happen anywhere. Areas directly outside of campus were still perceived as unsafe by many participants, although there was a general consensus that campus property was safe.

Sexual assault was believed to occur mostly during the evening hours, at parties, dorms, in homes, and in the summer. Although the participants were aware that sexual assault can occur at any time of the day, most thought about sexual assault happening in the evenings. Evening hours are when participants felt less safe even on campus, particularly in parking lots, shady areas where lights are burned out, and around tall bushes. Additionally, going to bars and drinking were mentioned as contributors to sexual assaults. Female dress style in these locations was also referenced as to where and why sexual assaults occur: “If a girl’s like, dressed in clothes that are provocative or just show a lot.”

Discussion

This study examined the opinions of students and faculty members regarding sexual assault on their college campus and offered students the opportunity to engage in community psychology research and practice. Seven themes emerged from the focus groups: personal experience, scenario response, resources, reporting, awareness, situations and locations, and university and administrative accountability. A number of these findings are in line with what other researchers have found regarding a university’s culture concerning sexual assault (Worthen & Baker, 2014) along with factors aligning with Wichita State’s unique ecological context.

Catalyst for Change

Several changes on campus resulted from this research and action project. Regarding awareness, resources, and university and administrative accountability, both student involvement personnel and the Title IX coordinator have collaborated on ways to widely disseminate the results of this work. A three-year Center for Disease Control (CDC) grant will allow surveys to be conducted by the Equal Opportunity and Title IX offices on campus that address student perceptions of sexual assault on campus. Additionally, a student-run Title IX committee has been established to plan events that highlight Title IX, advocate for students’ rights, raise awareness regarding campus policy change related to Title IX issues, and attempt to connect with other Title IX student committees nationwide. These steps will help address students’ requests for more education and awareness being brought to the issue of sexual assault.

Culture was also reflected in scenario responses and the reaction to location reported by focus group participants. These participants were not clear on when to intervene if a situation got out of hand or whether something that happens off campus is reportable. More education and practice is needed for students to know when to intervene appropriately and how to identify when an individual may be at risk for a sexual assault. Many stated during the focus group they were totally unsure about the various scenarios that were discussed. The campus has recently implemented a bystander intervention course, available on all students’ university homepage. This course touches on many of the issues participants in the focus group brought up as worries and challenges. In addition to the new training course, bystander intervention will ideally be made more visible with the newly implemented student committee and the results of the CDC Title IX survey.

Focus group participants were clear that reporting was an issue they believed was not adequately addressed. If someone did come forward to report an incident, they believed the incident would be “swept under the rug” or there could be backlash experienced by the survivor. In sharing results with the Title IX office, we learned that the process is not widely understood, especially with respect to how the university must respond to allegations. Because the reporting process in place currently requires the university staff to remain neutral, it can cause additional distress or lack of trust for the person reporting an assault. While impartiality is important in adjudication, it can also unintentionally communicate a lack of support, increasing the trauma for the survivor. As a response to the dissemination of these results, the Title IX office is actively pursuing an advocate system, and they have established a memorandum of understanding with Wichita Area Sexual Assault Center.

Finally, focus group participants were able to problem-solve on their own and generate a list of potential resources, but the university’s role was considered unclear and difficult to navigate. No university programs or offices (beyond the Counseling and Testing Center and the campus police) were identified as a specific resource. In sharing these results and generating discussion on campus, it became clear that the university culture was not conducive to providing support to survivors of sexual assault, nor was it structured to prevent future issues with timely, sensitive communication to the community. Focus group participants were concerned about how sexual assault incidents were resolved once a case was brought to the attention of administration. Participants noted that nothing was ever reported back to the student body after an incident was reported, which raised anxiety and doubts about the support they might receive. The increased visibility that has come from this work has catalyzed administration plans for transparency, changes in policy, and overall greater support for survivors.

Ecological and Cultural Successes and Challenges

Engaging all stakeholders to participate in this process is essential to any ecological change that might occur. The Community Psychology Association initiated the conversation as a way to increase the awareness of organizational responsibility when it comes to sexual assault, which has occurred as a result of these efforts. Some of the major changes include:

Of course, the original project sought to incorporate male perspectives, but encountered difficulties with recruitment and participation. This highlights the initial lack of engagement with the issue as well as the necessity to find a way to bring males into the conversation and recognize their role and responsibility regarding the issue of sexual assault. Additionally, male students who participated typically had a specific reason for choosing to be a part of the focus groups, and many of them cited that they did not believe they had any part in the solution. It is important to identify why men, particularly faculty and staff, were unwilling to participate so that all stakeholders can be involved in a solution.

Final Thoughts

This study provided valuable insights on the issue of sexual assault on campus, especially with respect to extending and expanding the use of community psychology competencies in the university community. This process has already begun, with the implementation of a student-led Title IX group and a newly created university-wide climate survey addressing the issue. Among the actions and practices that might grow from this investigation and the resulting programs and resources are strategies for increasing awareness of sexual assault and reducing its incidence. Ongoing evaluation and improvement of Wichita State’s reporting procedures and resources can create a campus culture that both broadly understands sexual assault and sets precedence for zero tolerance. The issue of sexual assault has gained visibility and momentum on college campuses across the nation, and faculty, staff, and student input are needed to create a campus culture that is safe and open for survivors to come forward. Policies need to be thoughtfully explored, implemented, and properly enforced so that perpetrators are fairly punished and college students feel safe and supported. Without the involvement of the Community Psychology Association, these difficult conversations and work would not have been accomplished with such broad campus support at Wichita State.

During the process of the research project, the Community Psychology Association was able to engage their membership and involve students, faculty, and staff to gain a deeper perspective on the issue of sexual assault. The process also allowed greater visibility for the organization and garnered interest in both the organization and community psychology as a discipline and its doctoral program. As a result of their growing profile within the campus, a Community Psychology Association monthly bulletin was created that highlights one competency each issue and includes interviews with practicing community psychologists who can provide insight from their real-world experience in the field. The entire process served as a powerful example of what can happen when a group of engaged and passionate students come together for the common goal of making their campus a better place.

NOTES

[1] All student statistics are reported by Wichita State University through their office of Planning and Analysis: http://www.wichita.edu/thisis/home/?u=opa

References

Boyatzis, R. E. (1998). Thematic analysis: Coding as a process for transforming qualitative information. Sage Publications.

Cantor, D., Fisher, B., Chibnall, S., Townsend, R., Lee, H., Bruce, C., & Thomas, G. (2015). Report on the AAU Campus Climate Survey on Sexual Assault and Sexual Misconduct. Rockville, MD: Westat.

Dalton, J. & Wolfe, S. (2012). Education connection and the community practitioner. The Community Psychologist 45(4), pp. 7-13.

Hsieh, H. F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative health research, 15(9), 1277-1288.

Marti-Costa, S. & Serrano-García, I. (1983). Needs assessment and community development: An ideological perspective. Prevention in human services, 2(4), 75-88.

Miller, B. (2014, Sept. 8). “WSU Officials Investigating Campus Rape.” Retrieved September 30, 2015 from http://ksn.com/2014/09/08/wsu-officials-investigating-campus-rape/

Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network. (2009). Who are the Victims? Retrieved September 17, 2015, from https://rainn.org/get-information/statistics/sexual-assault-victims

Sexual & Relationship Violence Prevention. (2016, December). Division of Student Affairs. DePaul University. http://offices.depaul.edu/student-affairs/support-services/health-wellness/sexual-relationship-violence-prevention/Pages/default.aspx

Smith, T. (2015, August 12). “Curbing Sexual Assault Becomes Big Business On Campus.” All Things Considered, National Public Radio. Retrieved from: http://www.npr.org/2015/08/12/430378518/curbing-sexual-assault-becomes-big-business-on-campus.

Sunflower. (2014, Sept. 8). “Rape reported at Shocker Hall: University police investigating an incident reported on Labor Day.” Retrieved October 8, 2015 from https://thesunflower.com/5678/news/rape-reported-at-shocker-hall-university-police-investigating-an-incident-reported-on-labor-day/

White House Task Force to Protect Students From Sexual Assault. (2014, April). Not alone: The first report of the White House Task Force to Protect Students From Sexual Assault. Washington, DC: Author.

Worthen, M. G. F. & Baker, A. (2014). “Consent is sexy”? Analyzing student reactions to a campus mandatory online sexual misconduct training program. Sexual Assault Report, 17(5).

Download the PDF version for the full article, including all tables, figures, and appendices

Table 1: Focus group themes with code counts based on group make-up |

Daniel Clifford, Nicole M. Freund, Jasmine A., Douglas, Julia Siwierka, Anna Turosak, Rhonda K. Lewis, PhD, Jessica Drum, Deborah Ojeda-Leitner, Refika Sarionder, Anna Caroline Chinnes, & Paige Keller

Daniel Clifford, Nicole M. Freund, Jasmine A., Douglas, Julia Siwierka, Anna Turosak, Rhonda K. Lewis, PhD, Jessica Drum, Deborah Ojeda-Leitner, Refika Sarionder, Anna Caroline Chinnes, & Paige Keller

Dan Clifford, Ph.D., is a Post-Doctoral Research Associate for the Sedgwick County Division of Health in Wichita, Kansas. Dan works for the Public Health Performance Subdivision and assists health department programs with data collection, analysis, and program evaluation and provides technical assistance to the fetal and infant mortality review group of Sedgwick County. He is interested in mindfulness interventions, particularly pertaining to post-traumatic stress disorder, and trauma-informed systems of care. Dan is also an organizer for the HomeFront Initiative, a community-based program that uses veterans to teach mind-body self-care and leadership skills to other veterans and first responders in the Wichita community. Email: dclifford11@gmail.com. Corresponding address: 1845 Fairmount Box 34 Wichita, KS 67260-0034.

Nicole M. Freund, MA, MBA is a research associate with the Center for Applied Research and Evaluation at Wichita State University’s Community Engagement Institute. She is a doctoral candidate in the community psychology program at Wichita State and holds a Master of Arts in both English and psychology (Northern Illinois University, Wichita State) as well as a Master of Business Administration (Wichita State). In addition, Nicole has over a decade of experience in the private sector working in marketing research. Her graduate work in the Community Research, Assessment, and Methodology lab includes research on the federal drug re-entry court in the District of Kansas (Kan-Trac) and social network analysis for offenders re-entering communities in Kansas.

Jasmine Douglas, Ph.D. has experience in program evaluation, management and development, prevention and intervention research, statistical methods, community based participatory research, empowerment, organizational development, leadership, policy, and consultation. Currently, Dr. Douglas is employed at James Bell Associates (JBA) and is the Associate Project Director on the National Cancer Institute project, Research-tested Intervention Programs. Dr. Douglas brings to JBA research skills in the areas of evaluation, survey design, quantitative and qualitative data analysis, literature review, and project management. Prior to joining JBA, Dr. Douglas’s research focused in the areas of tobacco control and prevention and community based research and action for sexual assault prevention by applying scientific methods to implement evidenced-based research programs. Julia Siwierka is a third-year graduate student in Wichita State University’s doctoral program. While her primary research interests focus on literacy and education, she is likewise passionate about preventing and raising awareness about sexual assault. As the current secretary for Community Psychology Association, Julia is coordinating a benefit production of The Vagina Monologues on campus as an extension of this research project. She also serves as the media relations coordinator for NAMI on Campus.

Anna Turosak is a third-year graduate student in the Community Psychology doctoral program at Wichita State University. Her research interests include understanding the factors related to mental health and wellbeing, community mental health, and working with college-aged populations to better understand their experiences and perceptions of mental health on their campus. Anna currently works at the Community Engagement Institute as a research assistant focusing on the evaluation of mental health services.

Rhonda K. Lewis, Ph.D., MPH is professor and chair of the psychology department at Wichita State University. She is a member of the Society for Community Research and Action and the Association of Black Psychologists. Currently, she is the advisor to the Community Psychology Association. She is also serving as one of the Serve-Learning Faculty Fellows at WSU. As a member of SCRA, she has served in a number of capacities being the Midwestern Regional Representative, Member at Large, Chair for the Council on Education Programs and Chair for the Cultural and Racial Affairs Committee. She uses behavioral and community research methodologies to promote health among adolescents and reduce health disparities. Dr. Lewis has over 20 years of experience in community organizing, program development and evaluation. She has over 50+ publications and 100 presentations at regional, national, and international conferences.

Jessica Drum received her PhD in Community Psychology from Wichita State University in 2016. She currently works as a UX Researcher at Facebook where she studies the ecology of social media. Previously, Jessica worked at the Center for Applied Research and Evaluation at WSU’s Community Engagement Institute. Her work was primarily focused on the evaluation of programs funded by Kansas’s Early Childhood Block Grants. Jessica also worked on a variety of topics during her graduate studies, including a computer intervention that worked to decrease loneliness and social isolation for older adults, and a sexual assault prevention study for college students. Jessica currently works at Facebook as a user experience researcher, utilizing her skills to understand and improve the experiences people have when using Facebook.

Deborah Ojeda-Leitner is a third-year Community Psychology graduate student at Wichita State University. Before graduate school, however, she proudly served as an AmeriCorps member in New York City and was involved in community health. Her interests include health, social justice, equality, social change community-based interventions and advocacy. Recently, she finished a project on health-related stereotype threats among the LGBT community and hopes to expand on healthcare, social justice, and public policy.

Refika Sarionder has earned degrees in Sociology (B.A., University of Bogazici, Turkey), in Sociology of Development (M.A. University of Bielefeld, Germany), and in Community Psychology (M.A., Wichita State University). Her research interests focus on gender issues, and religious and ethnic minorities. Over the last years, Sarionder has published academic articles and chapters in edited volumes on gender and heterodox minorities in Islam, and co-edited a volume on myths on creativity. Aside from participating in international research projects at German universities and research centers in Bielefeld, Heidelberg, Berlin, and Essen, she presented papers at national and international conferences. Sarionder served as a steering committee member of the Sociology of Religion group at the American Academy of Religion. She has worked and assisted in women’s counseling centers and shelters in Turkey, Germany and Switzerland. Currently, Sarionder is a board member of the Global Learning Center of Wichita (GLC).

Anna Caroline Chinnes recently received her Master of Art degree in Psychology at Wichita State University (WSU). She is currently in the Clinical/Community PhD program at WSU. For the past two years, she has worked as a member of the Grant Development team at the Community Engagement Institute in Wichita, Kansas, as well as one year with the Center for Applied Research and Evaluation. She holds clinical practicum positions at WSU’s Psychology Clinic and Counseling and Testing Center. She has enjoyed working on this important research with the Community Psychology Association and looks forward to future collaborations.

Paige Keller Born and raised in small town Cheney, Kansas, Paige Keller always had a spot for the “big city.” Ms. Keller started my college career at Butler Community College in 2012 and graduated with an Associate’s Degree in Liberal Arts. Then moved on to work on her Bachelor’s Degree in Psychology with a minor in Criminal Justice at Wichita State University starting in 2014 and graduated in 2016. As of now, spring of 2017, she is in her second semester of Graduate School and working on her Masters’ in Criminal Justice. Her ambitions are to go into law enforcement either in Wichita, Ks or Tulsa, OK. She would like to work in a specialty unit within law enforcement like SCAT which is street level drug crime enforcement. Eventually she would like to move up to the federal level and work in DEA.

agregar comentario

![]() Descargue la versión en PDF para acceder al artículo completo, incluyendo tablas y figuras.

Descargue la versión en PDF para acceder al artículo completo, incluyendo tablas y figuras.

palabras clave: Community Psychology Practice Competencies, Sexual Assault, Research and Action