The purpose of this paper is to provide a description of how the community psychology practice competencies are taught in the fieldwork practicum course at two PhD programs in community psychology. An overview of the educational approach and program goals are provided as well as a detailed description of how the course instructors utilize the practice competencies in the practicum courses and the kinds of projects that students conduct to learn the competencies. Comparison of the competencies addressed in each program and lessons learned are provided about program evaluation, graduate education training goals, and fieldwork sequence foci.

Download the PDF version for full article, including all tables, figures, and appendices.

The purpose of this paper is to present how two community psychology PhD programs in the U.S. have used and taught the Community Psychology (CP) Practice Competencies in our curricula, particularly in our fieldwork practica courses. The two programs are at DePaul University and National Louis University (NLU) in Chicago. Each of our programs has used the practice competencies in a variety of ways, from using the list as a self-assessment tool for students to determine their strengths and limitations and guide their project selection, to faculty reflecting on the extent to which each competency is developed within our training programs, and to determine areas of improvement. Further, DePaul’s program is a traditional PhD program while NLU’s program targets master’s level full-time professionals with strong community-based experiences, but with less traditional academic credentials. Each program is distinct; a comparison of the fieldwork practica courses and the competencies addressed offers important lessons for education programs and training for the field. It is important to note that students in both programs gain exposure to CP Practice Competencies in other parts of our curricula, but we focus only on the fieldwork sequences in this paper. These sequences provide both DePaul and NLU students the opportunity to apply what they learn in our curricula and to hone their CP practice skills.

Given the differences in the two graduate programs, the students who enter our programs and their career goals vary. NLU students tend to have more years of community and professional experience when they enter the PhD program and already have established relationships in their communities. DePaul students tend to be diverse in their experiences from students who enter the PhD program immediately after receiving their bachelor’s degree to those who have been working many years as a researcher and/or practitioner. DePaul graduates of the community psychology PhD program pursue a variety of careers, with approximately over a third in practice/evaluation careers (e.g., consultants for nonprofits, evaluator at a nonprofit or governmental organization), over a third in traditional faculty positions, 20% in full-time research positions, and a few in staff/administrative positions at universities. About a third of DePaul graduates from the clinical-community program are in full-time clinical careers, a third in full-time research careers, and a third who do about half clinical work and half research. Approximately 80% of NLU students go into practice-oriented, non-academic positions (e.g., executive directors of and consultants for community-based and not-for-profit organizations) working, for example, with homelessness, education, and youth. The fieldwork sequence not only increases DePaul and NLU students’ proficiency in CP practice, but also positions them to become more marketable for a variety of careers.

Recent Training in Community Psychology Practice

The role of a community psychologist is complex in that it depends on the integration of various values, competencies, and skills towards creating more just and fair societies (Sarkisian & Jimenez, 2011). Whether working at a non-profit organization, a research institute, a university or a government setting, the integration of community psychology values and competencies into local cultural communities is critical to being more effective in facilitating, managing, or demonstrating the need for change. Toward this end, it is important to examine how we prepare students for being effective community change agents and examine how we can better support them.

There have been several surveys conducted across all levels of education in CP to assess the extent to which the SCRA practice competencies are emphasized by programs (Brown, Cardazone, Glantsman, Johnson-Hakim, & Lemke, 2014; Connell, Lewis, Cook, Meissen, Wolff, Johnson-Hakim, 2013; Dziadkowiec & Jimenez, 2009; Gatlin, Rushenberg & Hazel, 2009; Neigher & Ratcliffe, 2010). The survey findings provide insight to how students experience the learning of practice competencies across programs, and how students are trained on these competencies across the field. Overall lessons learned across surveys include: 1) programs emphasize different competencies depending on their unique contexts, yet most tend to emphasize the ecological perspective and participatory community research; 2) doctoral programs tend to emphasize more research-based competencies; 3) students report they receive slightly less than what they prefer to receive in each of the core competencies; and 4) students reported preference for certain competencies that they were not yet learning, including consultation and organizational development, community development, resource development, prevention and promotion, and small and large group processes. In summary, it remains clear that while some programs are doing fairly well at training across certain competencies, there remain gaps in education.

In order to intentionally support the training of more effective community psychologists, the practice competencies were developed so that educators are clearer about the content of their CP training curricula and to help them articulate how their programs help students learn certain practice competencies. Although our field has a list of core practice competencies (Dalton & Wolfe, 2012) that educators can use to plan, implement, and evaluate their programs, concrete examples of how practice competencies are addressed can be helpful. Therefore, we provide case study examples of how our programs have integrated various community psychology practice competencies into our curriculum, particularly in our fieldwork practica courses.

There are similarities across NLU and DePaul in what practice competencies are emphasized in both our programs (see Table 2). Similar to the findings from previous surveys (e.g., Brown et al., 2014), both of our programs emphasize certain competencies at the program level. For example, the ecological perspective is integrated throughout our curricula. Other competencies are emphasized specifically in the fieldwork sequence. For instance, both DePaul and NLU students learn ethical and reflective practice through assignments and discussions, take a course in program evaluation, and gain experience with consultation and organizational development. Students in both programs also take a course in consultation, and they typically begin their fieldwork projects by learning about an organization’s needs and figuring out how to build capacity. Inherent in the focus on capacity building is an opportunity for students in both programs to gain experience with empowerment. Other competencies are dependent on the nature of student projects at both universities. For example, some students get experience in prevention and health promotion; small and large group processes; resource development (e.g., grant writing); and/or collaboration and coalition development. Next we provide an in-depth examination of how the CP practice competencies are taught in the DePaul and NLU fieldwork sequences.

DePaul University as a Case Study

DePaul University has a clinical community psychology PhD program that is 48 years old and a community psychology PhD program that is 16 years old. The programs are traditional PhD programs, and students are trained to become researchers, innovative designers of interventions,

collaborators, educators, practitioners, and evaluators. Training focuses on health promotion, empowerment, prevention and intervention, and evaluation at multiple ecological levels with diverse populations and organizations. Students are also trained to conduct community-based research to understand and address social problems, and receive this training in their coursework, graduate assistantships, and in their theses, comprehensive projects, and dissertations. Students are also trained to teach in university settings, to write competitive research grant applications, to present their research at local and national conferences, and to publish their research. An important focus of both doctoral programs at DePaul is the fieldwork sequence.

Description of Fieldwork Sequence

The fieldwork practicum course is part of a larger sequence in our graduate curriculum and is an opportunity for students to learn and apply CP practice competencies. Graduate students in both the clinical community and community psychology PhD programs are required to take three courses (i.e., Advanced Community Psychology, Principles of Consultation, and Seminar in Program Evaluation) before they enroll in the fieldwork practicum course[1]. The learning goals of the fieldwork course are to a) carry out a consulting project in which students apply the knowledge they gain in the community psychology curriculum, and b) gain entrée into a setting, develop collaborative relationships with staff, negotiate a contract, carry out a project, and write up and present a final product to a community agency.

The fieldwork course is an academic year-long course, and students spend 2-4 hours/week on their projects. Community psychology PhD students take the course in both their 2nd and 3rd years of graduate school (6 terms total), while Clinical-Community Psychology PhD students take the course in only their 3rd year (3 terms total). During the year, students develop and implement a consultation project with a community organization, under faculty supervision, and with peer input. It is expected that the project is conducted collaboratively with a community partner and that the project adheres to 15 guiding principles, such as a) the project requires significant use of community psychology theory, values, and practice, b) the project is not primarily basic research, c) the student treats participants and/or clients ethically, and d) the host setting has the resources, motivation, and track record necessary to follow through on their responsibilities.

Fieldwork is a blended on-line and face-to-face course. Some of the class activities are done on-line while others are done face-to-face. For instance, assignments include private journals that are submitted on-line and online discussion boards to keep the instructor up-to-date on the progress of student projects, but to also reflect on the process of engaging in their projects, relationships they are developing, ethical practice, and how they are applying what they have learned in the graduate curriculum to their projects. In the discussion boards, students are asked to integrate community psychology theory and principles into their responses and in their feedback to peers to help them apply what they have learned in the classroom to the real world. Course assignments also include a proposed project presentation, contract, mid-year progress report, final product, and final project presentation. Face-to-face class meetings are held periodically in order to conduct presentations and to have group discussions about specific topics, such as how to document and disseminate evaluation findings to a lay audience. Finally, the instructor has one required individual supervision meeting with each student per quarter, but students are free to meet with the instructor as often as necessary.

Students conduct a variety of projects in diverse settings, and their projects are typically program evaluation, program development, and/or grant writing. The instructor does not select the organizations or projects for the students in order to give them the flexibility and independence to select projects that suit their interests and skills. The majority of organizations that students conduct their projects with are community-based, non-profit organizations outside the university. However, about one student each year conducts a fieldwork project with an organization on campus. For example, a student conducted a process evaluation of a peer mentoring program for LGBTQA undergraduate students at DePaul University.

Application of the Practice Competencies in the Fieldwork Course

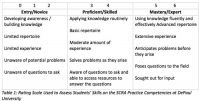

In the first week of the course, students are asked to complete a survey in which they assess their skill set for each of the SCRA CP practice competencies. For each competency, students rate their skills on a scale from 0 (Entry/Novice) to 6 (Mastery/Expert; see Table 1). Students then engage in an on-line discussion board in which they are asked to report strengths and limitations of their skill set based on their survey responses, and to discuss the ideal fieldwork project they would like to engage in during the school year and why. Students are asked to use this reflection to help them determine the kind of organization and project they would like to carry out in the course. Some students select a project based on their current strengths while others select a project based on their limitations. For instance, some students feel that they are stronger in program evaluation but want additional evaluation experience because they envision their future career involving this competency, and as such, they would like to gain as much experience as possible in evaluation. Other students use fieldwork as an opportunity to learn a new competency. For example, a student dedicated her fieldwork project to developing infographics, a new skill, to disseminate findings of a recent evaluation she conducted with her community partner.

At the end of the school year, students engage in a discussion in which they discuss the CP practice competency they selected and how their project helped them to improve that skill. Students also talk about which practice competency they would like to develop the following year if they were to work with the same organization again by discussing the kind of project they would work on to help them develop that skill. These types of reflections are beneficial for getting students to be intentional in selecting experiences that help them meet their career goals. Given that our curriculum does not adequately address every CP practice competency, giving students autonomy in project and site selection allows students to tailor their training experience towards their interests and towards competencies in which our program is weaker.

Table 1: Rating Scale Used to Assess Students’ Skills on the SCRA Practice Competencies at DePaul University (see PDF version or JPG at the end of the article)

There are some practice competencies that are taught in the curriculum, such as prevention, ecological principles, consultation, program evaluation, grant writing, prevention and intervention, empowerment, and public policy[2]. With the exception of ecological principles, we have dedicated courses on each of the other competencies. The competency of Ecological Principles is integrated throughout the curriculum and in much of the research that faculty do, which is consistent with previous research on the CP practice competencies and graduate training (Brown et al., 2014). With regard to competencies in which the program is weaker, students are encouraged to seek coursework outside of the department or to gain experience in either fieldwork or through other work (e.g., research/evaluation projects).

In the fieldwork practicum course, the competencies that students typically gain exposure to and/or experience in are ethical reflective practice; program development, implementation and management; consultation and organizational development; empowerment; community education, information dissemination, and building public awareness; and/or program evaluation; but this also varies by student project. Students complete a journal entry and a discussion board post in which they write about ethical, reflective practice. Further, every time students submit a journal to the instructor or meet with the instructor face-to-face, they are asked to report any areas in which they need support, including ethical dilemmas. Empowerment is also emphasized in the fieldwork course, particularly in their approach to working with the organizations. The instructor

encourages students to “enact empowering processes through working in genuine, inclusive partnerships with community members and organizations” (Dalton & Wolfe, 2012, p. 10). Students are asked to view the organizations and members as community partners with whom they collaborate. Some students, however, report that this collaborative and empowering approach is difficult to do when they have little time to dedicate to the project or when the community partner really just wants them to do the project without much consultation from the community organization (i.e., when the community partner does not have time or the inclination to deal or work on an issue and wants the consultant to simply be an extra pair of hands; Block, 2011).

All fieldwork students are exposed to community education, information dissemination, and building public awareness. The instructor provides a workshop to students in which we discuss how to communicate evaluation findings to a community partner and the various ways to disseminate results (e.g., infographic, evaluation reports). In that workshop, students practice revising jargon-filled evaluation findings for a lay audience. They also learn the most effective ways to communicate survey findings in graphs and figures using strategies recommended by data visualization experts (e.g., Evergreen, 2013).

Typically, at least a third of the class conducts a program evaluation. For instance, a student developed evaluation tools for a community-based organization that serves adults who are homeless (see Appendix I: Case Study #1). The student spent the whole academic year developing and refining the tools. First, she spent time with the organization staff determining what they wanted to evaluate and learning about the specific program to be evaluated. Second, she developed process evaluation and outcome evaluation tools based on her conversations and meetings, which she shared with the staff for feedback. Third, once she obtained their feedback, she participated in the program for a couple of days in order to observe the program in action. This experience was important because she learned that some of the evaluation questions did not apply as not everyone received all parts of the program. She also shared the survey draft with the consumers of the program who provided feedback on the wording of questions. Fourth, she revised the survey based on her participation in the program and discussions with consumers. Fifth, she shared the revised draft with program staff for additional feedback. Lastly, she wrote a training manual for the staff on how to administer the survey to consumers and enter the data. Thus, she took an empowerment approach by increasing the evaluation capacity of staff.

A couple students each year gain experience in program development. For instance, a student developed the curriculum for a local peer mentoring program at a community based organization. In order to develop the curriculum, she spent time at the organization talking with staff about the program, reviewing documents about the mentoring program, and reviewing the literature on peer mentoring for first-generation college students. The student and the staff collaboratively developed the program goals and the general format for each mentoring session. These initial steps enabled her to write the curriculum, and she shared each session curriculum draft with staff and youth for feedback.

Some competencies are completely student dependent, such as participatory action research (PAR). For instance, a student gained experience and expertise in PAR (see Appendix II: Case Study #2) by working with an alternative high school over a two-year period in which she collaborated with students on developing, carrying out and disseminating findings from a restorative justice PAR project.

There are certain competencies in which our students at DePaul typically do not gain experience in our fieldwork sequence, such as community organizing and public policy analysis, development and advocacy. Although students have the opportunity to take a course in public policy at DePaul, and thus gain exposure and experience in that particular course, perhaps these competencies could be addressed in the fieldwork sequence so that students could gain further experience and possibly expertise if the assignments and expectations in the course are changed.

In sum, the SCRA practice competencies are used as a guide for students to select their fieldwork projects and to reflect on their professional development while in graduate school. Online discussion boards and journal entries are used to help students develop their projects but also reflect on their competencies. Students typically gain exposure to and/or experience the following competencies in the fieldwork sequence: ethical reflective practice; program development, implementation and management; consultation and organizational development; empowerment; community education, information dissemination, and building public awareness; and/or program evaluation, but this also varies by student project. The experiences that students gain in the fieldwork sequence also helps students network with community organizations and professionals, which sometimes lead to job opportunities, evaluation contracts, or dissertation projects.

National Louis University as a Case Study

The NLU CP doctoral program is a newer program (7 years old) and is conceptualized as a community intervention in the Chicagoland area, aiming to build a network of diverse, social change agents sharing the common values of the field. A unique aspect of this program is that most students are full-time professionals in this metropolitan area practicing in CP-related or compatible fields, and they plan to remain in the area upon completion of their degrees. We hope our graduates will embody the core values of the field in the unique positions they hold within the local community. Theoretically, values such as citizen empowerment, appreciation for diversity, promotion of sense of community, collaboration based on community strengths, and empirical grounding using participatory community research methods will all lead to more socially just practices and inclusive settings for the highly diverse communities of Chicago. Using this program logic, we place critical importance on learning the CP practice competencies, including consultation and organizational development, community development, resource development, prevention and promotion, and dynamics of small and large group processes.

Fieldwork and Consultation Course Description

NLU’s experiential fieldwork/consultation sequence is designed to give students an opportunity to learn about various communities they seek to work with while in the program and beyond. The sequence enables students to apply concepts learned in the classroom to real-world action projects that serve the local community. Students gain hands-on community experience as they pursue personal learning objectives and professional development skills related to CP in a variety of settings (see Table 2). While we view all of the SCRA practice competencies as critical competencies to be gained and refined throughout the program experience, the competency of ethical, reflective practice is a main component and integral to the fieldwork sequence.

Table 2: Practice Competencies Addressed in Both Programs (see PDF version or JPG at the end of the article)

Across the entire program experience, there are four 10-week fieldwork courses spread across 18 months, and a 20-week culminating consultation project with a local organization. Students engage in a minimum of five hours of fieldwork per week in tandem with other coursework. In blended face-to-face and online formats, instructors set specific fieldwork deliverables for the first four terms; students establish mutually agreed upon consultation deliverables with their partner organizations for the last two terms. In order to reflect on their fieldwork experiences and on their progress in the application of CP practice competencies, students write discussion-board posts and complete assignments for both instructor and peer feedback, engage in periodic face-to-face and virtual group sessions, and meet as needed with instructors individually to discuss questions or concerns. Some of the fieldwork assignments align concurrently with other courses to provide content and experience that will bring synergy to the application of theory to practice.

Fieldwork I: Personal-Professional Logic Model

This first fieldwork course encourages students to intentionally examine personal and professional goals as they relate to the broader community they hope to influence. Students practice the sociocultural and cross-cultural competence by self-reflecting through a Personal-Professional Logic Model (see Appendix V) and a CP consulting resume, considering the unique resources they bring to the community on their issue of interest, and identifying the unique, existing resources within the community. After this exploration, students identify organizations and people most important to connect with on the issue and then strategize about how to network with these individuals and build relationships with them. Throughout this process, students learn professional development skills related to several core competencies including the ecological perspective, sociocultural and cross-cultural competence, community leadership and mentoring, and possibly community education. As students consider how best to present themselves to potential partners, they practice initial relationship development. Other key deliverables for Fieldwork I are the identification of two CP practitioners from the SCRA “Connect to a Practitioner” tool (http://www.scra27.org/what-we-do/practice/connect-practitioner/) and two representatives of potential local partner organizations. Students contact one of each related to their interests. Students share their logic model and resume with the CP practitioner, and they develop a rationale for connecting with the organizational representative specific to their needs and interests. While engaging in professional development opportunities, students also reflect on their networking and relationship-building skills to understand more clearly how to connect assets more dependently in the future.

Fieldwork II: The Community Profile

The focus of Fieldwork II is the application of the ecological perspective in the assessment of students’ geographical community of interest. Students develop the Community Profile, which provides an opportunity for in-depth learning about various communities for potential future collaboration. Prior to engaging with a community, it is important for a community psychologist to learn about the structural, historical, economic, cultural, and programmatic context of a community area, and as a result, students spend time doing this as part of their assignment. Working under the assumption that no sincere effort to address a social problem will occur outside of

the social, cultural, and political dynamics that exist in that area, students practice aspects of a variety of competencies as they meet the major goals of this course. The tasks associated with Fieldwork II involve several aspects of the core competencies besides sociocultural and cross-cultural competence, including resource development; collaboration and coalition development; community development; and public policy analysis, development, and advocacy. Completing the community profile requires that students: a) learn how historical decisions regarding community development influence perceptions of and resources for their social issue (e.g., community and political lines drawn that have implications for developing and using social power or other resources), b) explore the various perspectives of the many stakeholders in that area on the issue, c) build relationships with the important key players and local leaders on the issue, d) identify the social and cultural capital that exists to address this social issue, and e) learn what programs, policies, coalitions, and funding sources exist to address the issue.

Students also work to understand the extent to which a community is ready to take action on the issue of concern to them and next steps while building a reputation for themselves as educated, respectful, and ethical collaborators on this issue. In addition, although not the primary purpose of this assignment, students reinforce their research knowledge by collecting and synthesizing relevant community data from a variety of sources (e.g., public records, websites, newspaper articles, in-person or phone conversations with community members, observations in the community).

Choosing one community of focus, students make a minimum of one personal contact; organize and condense large amounts of data collected, determining critical information for the profile; and practice clear and concise writing. Although many of our students are already knowledgeable about the dynamics that perpetuate the issue of concern, this course ensures a more objective assessment of the cultural landscape of the issue before taking action. The community profile is then used as a resource for the development of later materials and assignments, such as the development of a prevention program, policy, or community intervention (e.g., a coalition) to address the social problem of concern.

Fieldwork III: Community and Member Leader Profiles

In Fieldwork III, students meet community members for further relationship building and future collaboration. This course has two points of focus: 1) the use of narrative interview approaches to enhance understanding of research projects, whether in the design, data collection, or interpretation stages of the process, and 2) informing students’ current research projects in a way that adds depth to that research, regardless of the stage.

In meeting the goals of this course, students practice the competencies of participatory community research, community inclusion and partnership, community leadership and mentoring, and sociocultural and cross-cultural competence. Students gain experience in participatory community research by developing one leader and one community member profile reflecting the narrative of a community. Students are challenged to connect prior learning from the qualitative methods and survey design courses to structure their interviews and develop quality questions based on an in-depth interview guide. Course instructors provide extensive advice and feedback on drafts of the interview protocol before students conduct and record in-person or telephone interviews. From the interviews, students learn aspects of a community and apply CP principles to make sense of their interviewees’ life stories, current roles in the community, work practices, and their perspectives on the future. As individuals and as part of organizations and communities, students reflect on aspects that may overlap with their own life and career goals.

In addition to gaining experience in conducting qualitative interviews, students practice capturing relevant information in note taking, organizing and synthesizing large amounts of narrative interview data concerning interviewee experiences and their impact on who they are today, determining important pieces for each profile, and practicing clear and concise writing. Students also collect contextual data from a variety of sources (e.g., public records, websites, conversations with community members, newspaper articles, observations in the community). Furthermore, in multiple, brief papers about their interviewees, students connect their findings to CP-related theories to explain and understand the perspectives of the interviewees. Ultimately, they determine how to use this data to inform their own research projects.

Fieldwork IV and Consultation: Proposal and Contract Development / Consultation Experience

By the time students begin Fieldwork IV, they have a fairly clear understanding of their research area of focus and the community with which they will work, and they have built relationships with key community members. The goal of this 20-week course is for students to plan and carry out a CP project with a community organization. These projects may emphasize program evaluation, research, advocacy, non-profit management, social marketing, community organizing and development, or fundraising.

The competencies that students gain in this practicum course vary. Some students work on community leadership and mentoring; others focus on small and large group processes and resource development in their projects. The collaboration and coalition development competency is a focus of some student consultations; community development and advocacy is addressed by others. Some students complete projects with a focus on community education, information dissemination and building public awareness; participatory community research, grant writing; and program evaluation. Examples of consultation projects are the development of a community health coalition and the installation of a community garden (see Appendices III and IV: Case Studies #3 and #4).

In collaboration with the partner organization and with significant instructor guidance and feedback, students develop a project plan for their community consultation. They draft and re-draft the proposal in collaboration with the instructor and organizational representative. In order to initiate the consultation period, students create and sign a contract or Memorandum of Agreement to add to the Scope of Work.

At regular intervals throughout the consultation period, students are in contact with the instructor and peers through an online discussion board to report on their progress or on any problems that occur. In final presentations, student share the stories of their projects with classmates and future cohorts: how they used the knowledge and skills gained in the program to inform the project, successes, challenges, what they would do differently in the future, advice for the next group of students, and other lessons learned.

A Comparison of the Fieldwork Sequences and SCRA Practice Competencies in the Two Graduate Programs

There are multiple similarities and differences across DePaul and NLU in the fieldwork course sequences and in the practice competencies emphasized in the sequence. Students at both DePaul and NLU select their own community partner organizations based on their individual interests and expertise. Both programs use a hybrid online and face-to-face format for work done with instructors and classmates while they conduct their fieldwork projects. Both DePaul and NLU students submit progress and final reports and make presentations about their consultations. The fieldwork courses at both programs culminate into a final product that is provided to the community partner. Finally, both of the programs use the fieldwork sequence as an opportunity to help students apply what they learn in the curriculum to the real world and to practice their competencies under instructor supervision and peer support.

Given that DePaul offers a traditional PhD education while NLU offers a more practice oriented PhD program, the role of research is different in each program. At DePaul, students learn, apply, and gain expertise in participatory community research skills in multiple program requirements (i.e., methods/analysis courses, thesis, dissertation, comprehensive project, research assistantships with faculty, 3rd-year as the research year requirement). Thus, the instructor does not teach any research skills in the fieldwork course nor require any assignments that utilize students’ research skills. It is expected that students will apply other SCRA practice competencies that they may not utilize in the graduate program. However, if students conduct a program evaluation project with their community partner, they will naturally utilize their community research methods and analytic skills they learned in other curriculum requirements. In contrast, NLU students do not have as many requirements or opportunities to learn or conduct participatory community research skills. Thus, the NLU fieldwork sequence and student projects are directly tied to the program research path so that students better learn their research skills (preliminary research project building to the dissertation and parallel to coursework).

Another difference between the NLU and DePaul fieldwork sequence is that NLU students spend more time on self-reflection as a professional and on researching their community site before conducting their consultation project. The NLU fieldwork sequence begins with discovery of self as a community psychologist, followed by community discovery and exploration for two terms, then by consultation proposal and contract negotiation, and ending with the 18-week consultation project. NLU students spend a good deal of time researching the potential community before beginning the fieldwork project. In contrast, DePaul students engage in some self-reflection in their journals to the instructor while they conduct their fieldwork projects. They also assess their own CP practice competencies as a form of self-reflection, to select their potential projects and to examine their own development over time after they engage in their fieldwork projects. DePaul students also engage in self-reflection in other aspects of the curriculum (e.g., professional development seminar), but self-reflection is not necessarily tied to their fieldwork projects. Given the nature of the DePaul fieldwork sequence and that students conduct an academic-year-long project, students have less time to research their community site beforehand. However, some DePaul students conduct their projects with community organizations with which they already have a prior relationship. Other DePaul students conduct both of their fieldwork years at the same community site and thus benefit from their earned trust and longer-term relationship. The benefit of NLU’s long-term relationship building, community researching, and self-reflection before engaging in their community consultation is that students may be able to conduct projects that are more fruitful or have fewer barriers. If a DePaul student is working with a new organization, there is the risk that the community project will not work out as planned because of unforeseen barriers.

The two programs share some CP practice competencies (e.g., empowerment, ethical and reflective practice). Competencies that diverge in the two programs are, in part, reflective of the student populations, training goals, fieldwork course goals, and the nature of the programs. For instance, for NLU students focus on the combination of such competencies as sociocultural and cross-cultural competence, ethical and reflective practice, community development, and prevention and health promotion reflects the self-discovery, awareness, and growth as community psychologists throughout the program, which concludes with their professional consultation. DePaul students typically gain exposure to and/or experience in the following competencies in their fieldwork sequence: ethical reflective practice; program development, implementation and management; consultation and organizational development; empowerment; community education, information dissemination, and building public awareness; and/or program evaluation. The fieldwork sequence is a culminating professional experience ending with a usable product that they present and give to their community partner and with a reflection on what they have learned from their experience.

Lessons Learned and Recommendations for Community Psychology Education Across the Two Programs

Based on our analysis of the application of the CP practice competencies in each of our fieldwork courses, we have identified practices that we would like to incorporate into our own programs that might also be helpful in other training programs.

Evaluation. It would be useful to conduct systematic evaluation of students’ learning of the CP practice competencies in the fieldwork sequence. Perhaps instructors can administer a pre- and post-course assessment of students’ level of experience/expertise in each practice competency to determine which ones they learned in the fieldwork practicum. Instructors should expect that students would only improve in some of the competencies depending on their specific projects. This assessment would also be helpful for students to reflect on their own professional growth and career goals and to determine next steps in their training plan. Further, it would be beneficial to evaluate which competencies are used among program alumni in their current jobs so that faculty can understand the kinds of competencies on which students should be trained in order to make them competitive for the job market.

Training Goals. Determine the training goals of the education program and how students will learn the SCRA practice competencies. Faculty should reflect on which SCRA practice competencies will be the focus of their program and the focus of their fieldwork sequence. Once the practice competencies are determined, how will students be assessed on those competencies?

Approach to Fieldwork Sequence. Determine the model for your fieldwork practica sequence. The models utilized in our fieldwork practica influence the CP practice competencies learned. For instance, the model at DePaul is that the student acts as a consultant. This model is not well suited for all practice competencies or for all of our students’ interests. Some students enroll in our program with a specific social problem for which they would like to create social change. They might be interested in influencing policy on a certain issue, but a community partner has not approached the student with that specific idea in mind. The philosophy in the fieldwork course is that the organization staff identifies the need and the student helps the organization to address that need. Thus, staff members do not typically articulate needing assistance with a policy issue, but instead they request support on program development, grant writing or program evaluation. Another way to conceptualize the fieldwork practicum is for students to select a CP practice competency (e.g., Public Policy Advocacy), and then the student carries out a project with a community partner to fulfill that competency, whether an organization requested it or not.

Rather than allowing students to select their organizations for their fieldwork projects, another approach to the fieldwork practicum is for instructors to select organizations and projects for students to carry out in small groups in the course. The projects each year could build on one another, which would enable long-term relationships between the program and community organizations. Ultimately, this approach could enable graduate programs, overall, to make a bigger impact. Although at DePaul the CP students may work with the same organization over a two-year period, the group model in which the instructor selects the projects and organization could have a bigger impact over a longer period of time assuming that the instructor works with the same organization for many years. Disadvantages of this approach are that students might work on projects that may not interest them and that fewer CP practice competencies would be applied across projects. The long-term impact, however, might outweigh these disadvantages.

Conclusion

No matter what careers students pursue when they graduate from our programs, many have expressed the importance of the practice skills they gained in their fieldwork projects, which they have utilized in their current careers. Some of our students have also developed long-term collaborations with their fieldwork organizations as a result of their experience and projects in the sequence. Other students have also learned about the kinds of careers or projects they do not want to pursue in their future careers, which has helped them to narrow down their career options. Although there are improvements we can each make to our fieldwork sequence, this course is a strength in each of our programs. Given that each of our programs do not provide students with the experiences to learn every CP practice competency, the fieldwork practicum is a great way to allow students to individualize their educational plans to gain skills in CP competencies they might not gain otherwise.

Author Acknowledgements: We would like to thank the reviewers as well as Danielle Vaclavik and Amy Anderson who provided feedback on earlier versions of this paper.

NOTES

[1] Students typically enroll in other CP relevant courses while they take the Fieldwork practicum, such as Grant Writing, Prevention & Intervention, or Public Policy.

[2] Public policy is a new course in DePaul’s curriculum as a result of a survey of graduate students about the SCRA practice competencies and which competencies students would like to gain more experience. Public policy was determined to be a weak area in the curriculum but also a competency that many students desired more exposure and experience.

References

Block, P. (2011). Flawless consulting: A guide to getting your expertise used. Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA.

Brown, K., Cardazone, G., Glantsman, O., Johnson-Hakim, S., & Lemke, M. (2014). Examining the guiding competencies in community psychology practice from students’ perspectives. The Community Psychologist, 47(1), 3-9.

Christens, B. D., Connell, C. M., Faust, V., Haber, M. G. & the Council of Education Programs (2015). Progress Report: Competencies for Community Research and Action. The Community Psychologist, 48(4), 3-10.

Connell, C.M., Lewis, R.K., Cook, J., Meissen, G., Wolff, T., Johnson-Hakim, S. (2013). Taylor, S. Special report – Graduate training in community psychology practice competencies: Responses to the 2012 survey of graduate programs in community psychology. The Community Psychologist, 46, 5-8.

Dalton, J., & Wolfe, S. (Eds.). (2012). Education connection and the community practitioner. The Community Psychologist, 45(4), 7-13.

Dziadkowiec, O., & Jimenez, T. (2009) Educating community psychologists for community practice: A survey of graduate training programs. The Community Psychologist, 42(4), 10-17.

Elias, M. J., Neigher, W. D., & Johnson-Hakim, S. (2015). Guiding Principles and Competencies for Community Psychology Practice. In Scott, V. C. & Wolfe, S. M. (Eds.). Community Psychology: Foundations for Practice (pp. 35-62). Sage Publishing, Inc., Thousand Oaks, CA.

Evergreen, S. D. H. (2013). Presenting Data Effectively: Communicating Your Findings for Maximum Impact. Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA.

Neigher, W.D., & Ratcliffe, A.W. (2011). Back to the Future, Part III. The Community Psychologist, 44(1), 13-15.

Sarkisian, G. & Jimenez, T. R. (2011). Guiding Principles for Education in Community Psychology Research and Action. The Community Psychologist, 44(4), 7-8.

Download the PDF version for full article, including all tables, figures, and appendices.

Table 1: Rating Scale Used to Assess Students’ Skills on the SCRA Practice Competencies at DePaul University |

Table 2: Practice Competencies Addressed in Both Programs |

Bernadette Sánchez, Tiffeny Jimenez, Judah Viola, Judith Kent, & Ray Legler

Bernadette Sánchez, Tiffeny Jimenez, Judah Viola, Judith Kent, & Ray Legler

Bernadette Sánchez is a Professor of Community Psychology at DePaul University. She conducts research on mentoring relationships and positive youth development among urban, low-income adolescents of color. Her research is on the role of formal and informal mentoring relationships in youth’s educational experiences. Bernadette also investigates the resilience of marginalized youth and issues related to race and ethnicity, such as racial discrimination and racial/ethnic identity. She authored literature reviews on the role of race, ethnicity, and culture in youth mentoring for the first and second editions of the leading scholarly handbook for youth mentoring. She has received funding for her research from private foundations as well as the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD). She is also a member of the Research Board for the National Mentoring Resource Center and received the 2014 Ethnic Minority Mentoring Award from the Society for Community Research and Action. Email: bsanchez@depaul.edu. Corresponding address: Psychology Department 1 E. Jackson Chicago, IL 60604.

Tiffeny R. Jimenez, Ph.D., is an Assistant Professor at National Louis University. She is a Community Psychologist, and Assistant Professor of Psychology within the School of Social and Behavioral Sciences. She is most passionate about creating more inclusive communities and socially just practices through organizational and community-level systems change; facilitating and evaluating coalition development; examining resource exchange sustainability, and developing educational opportunities that promote systems leadership. She has worked and written most on various community-based research projects spanning social justice issues, including: coordinating a collaborative statewide cross-disability leadership training initiative, consulting on initiatives to change the culture of a university to be more supportive of women faculty in the STEM fields, and conducting a collaborative network system analysis with a community-wide systems change initiative across a tri-county area assisting in the development of a data-driven capacity-building process to increase the knowledge of community members for restructuring a local human services system. She has recently published strategies for strengthening graduate programs in Community Psychology and to better educate for Community Psychology practice careers. She is most active in the Society for Community Research and Action and the American Evaluation Association. She is currently working to develop the infrastructure needed to support widespread community engagement across NLU and her most current work includes developing methods for assessing cultural communities.

Judah J. Viola, Ph.D., is Dean of the College of Professional Studies and Advancement at National Louis University. He is also a Community Psychologist, and Associate Professor of Psychology. Judah’s research and advocacy interests involve promoting healthy communities and increasing civic engagement and prosocial behavior. Judah has written most extensively on evaluation research including his book, Consulting and Evaluation with Nonprofit and Community-Based Organizations. His most recent writing project with Oxford University Press is an upcoming book on the diverse career paths in Community Psychology. He is active in the Society for Community Research and Action and the Chicagoland Evaluation Association. Judah serves on the Executive Committee of the Consortium to Lower Obesity in Chicago Children. His recent community-based evaluation projects have explored Neighborhood Revitalization efforts with Habitat for Humanity, and Restorative Justice efforts of Chicago’s Safe Schools Consortium.

Judith A. Kent, Ph.D. is an associate professor at NLU, where she earned her doctorate in community psychology. She teaches in the Community Psychology program and co-chairs and teaches in the Undergraduate Psychology program. Her background is in language studies and instruction, culture, and cross-cultural communication. A main area of research interest is language and identity of emerging adults. She works with persistence of underrepresented students through higher education. Kent is affiliated with Pilsen Neighbors Community Council of Gamaliel of Metro Chicago and a member of the University Round Table of PNCC/GMC, which is working on the development of a family college and career readiness program. Collaborating with NLU colleagues in a study of community resilience as a buffer for Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs), Kent focuses on the language and cultural context. She is also interested in international community psychology and is collaborating with colleagues in Florence, Italy, where she had lived and worked prior to joining NLU.

Ray Legler is an Assistant Professor of psychology in the School of Social and Behavioral Sciences at National Louis University in Chicago. Dr. Legler earned his Ph.D. in Ecological/Community Psychology from Michigan State University and has been working on urban youth and education issues in the Chicago area for over 15 years. Prior to joining the faculty at National Louis, he served as Director of Research and Evaluation at After School Matters in Chicago. Dr. Legler’s current research interests focus on community-based approaches to addressing and preventing urban poverty by building partnerships between high schools, post-secondary institutions, and businesses.

agregar comentario

![]() Descargue la versión en PDF para acceder al artículo completo, incluyendo tablas y figuras.

Descargue la versión en PDF para acceder al artículo completo, incluyendo tablas y figuras.

palabras clave: Community Psychology Practice Competencies, Community Psychology Education, Community Psychology Practice