Dialogue concerning competencies in community psychology practice has contributed to the articulation of undergraduate and graduate education in community psychology. This dialogue shares resources in applying community psychology competencies but lacks a voice—Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs). Historically Black Colleges and Universities have undergraduate courses and graduate programs in community psychology, yet, no one has written on competencies and "praxis" from these settings. This article uses reflective narratives from faculty and undergraduate students to illustrate the use of competencies in community psychology practice with a local community. The context of the institution, emerging from legal segregation in the south, and primarily populated by economically disadvantaged and ethnic minority students, models community inclusion, ecological perspectives, empowerment, value of socio-cultural diversity and reflective practice in a neighborhood revitalization project. Discussion centers on lessons learned and challenges in engaging in praxis across undergraduate settings and HBCUs.

Download the PDF version to access complete article, including Tables, Figures, and Appendices

Introduction

“You helped inspire me in ways that placed a fundamental access in my education. I might not have been the A student in your class or the ideal one, but I took all of you[r] lessons and implemented it in my life. I grew up in a home where my dad often verbally, mentally, and sometimes (very rare occasions) physically abused my mom. I have never told anyone about the issue because I didn't want pity from my at home situations. I grew up very isolated from my peers and I honestly hated high school. I came to college thinking that my community did absolutely nothing for me. After taking your course, I realize that a community is beyond geographic location. My community includes people that are in similar situations as I am. I have a desire to make a difference and now I know how to begin…Thank you so much for inspiring me and although your classes were a challenge for me, I appreciate you for pushing me to go past the mental limit I had set for myself.”

This is the voice of Tiffany; she sent this email after completing the Introduction to Community Psychology course at Winston-Salem State University. Tiffany and, to date, more than 60 undergraduate students at the university have had the opportunity to complete a community psychology course and, for her and others, it has transformed the way they think about themselves, community, and social justice (Henderson & Wright, 2014; Henderson, in press). These undergraduate students at a Historically Black University located in the Southeastern region of the United States are underrepresented voices in the field of community psychology practice. Many are first-generation and from economically stressed or disadvantaged households. We reflect on their voices and our own. This article answers the call, “How are the competencies being received and used in the field by academics and students” through short reflective narratives—writing from the standpoint of faculty and undergraduate students in a Historically Black University. We use a racial justice lens to lift the stories of African American undergraduate students and faculty out of the shadows of community psychology to reflect critically on our work with a neighborhood revitalization project.

Since the Dalton and Wolfe (2012) publication in The Community Psychologist, there has been great dialogue on using competencies in community psychology (Langhout, 2015; Wolfe, 2014; Wolfe, Chien, Scott, & Jimenez, 2013). Wolfe, Chien-Scott, and Jimenez (2013) presented a special issue of the Global Journal of Community Psychology Practice on competencies across international contexts, to include Western Australia, Italy, and Egypt. Wolfe (2014) provided reflection from the standpoint of practitioner, building on her experience in health disparities research and evaluation. Langhout (2015) articulated the application of competencies as both scholar and activist across class and racial settings. These reflections build knowledge in our field and the tensions across competencies in community psychology practice. However, this dialogue lacks representation of Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs). We argue HBCUs have a historic mission to racial justice and can model “praxis” of competencies across undergraduate education and with ethnically and economically diverse populations.

We begin our narrative with a history of HBCUs in the United States to articulate the racial injustice African Americans encountered and the tensions these institutions faced with community activism. We reflect on our work with the Waughtown Neighborhood Revitalization Project, from the standpoint of African American faculty and undergraduate students, in order to model community psychology competencies, community inclusion, socio-cultural diversity, ecological perspectives, empowerment, and reflective practice. We conclude with a discussion on lessons learned and challenges to elucidate barriers in translating theory to practice and community change, especially in this setting. We share our stories of “praxis” and write in the spirit of once enslaved African Americans who entered Historically Black Colleges and Universities in search of freedom, of Tiffany, and many other students who transitioned through the community psychology course.

Racial Justice and Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs)

In the United States, the notion of race is tied to a historical belief and value system predicated on color—specifically black or to be African American in the United States indicates a history of exclusion and violence (Christians, 2014; DeGruy, 2005; Glaeser & Vigdor, 2012). Notions of Whiteness and racial superiority further demoted African American children as intellectually inferior and denied them access to education (Christians, 2014). The end of the civil war and emancipation proclamation dismantled slavery in the United States but African Americans continued to face violence through peonage and segregated schools (DeGruy, 2005). Simultaneously, northern philanthropist and religious groups developed institutes and schools to educate African Americans on vocational trades in a post-slavery and racially segregated United States (Albritton, 2012; Wenglinksky, 1996). These institutions would evolve into Historically Black Colleges and Universities.

Many HBCUs relied on White funders, were developed around religious ideologies (e.g., Methodist) and were created with a political agenda. Whites controlled many HBCUs and comprised the majority of teachers and administrators; thus, education focused on vocational skill training and religious doctrine rather than political activism (DuBois, 1903; Woodson, 1933). Critics of HBCUs argued these institutions pacified African Americans and reinforced docility (DuBois, 1903; Hughes, 1934; Woodson, 1933). While HBCUs served as institutions primarily for African Americans from 1865 to the 1960s, they still encountered criticism from numerous African American activists. At one point in time, the African American poet, Langston Hughes (1934), called them “cowards” in the midst of social turmoil and civil unrest in the United States.

By the 1940s, African Americans were entering the military and shifting tides in the economic and political landscape of the United States required a new kind of workforce. More African Americans began to pursue higher education and, consequently, the political climate of HBCUs shifted. HBCUs became institutions of access for African American students who were denied admission into Historically White Institutions (HWIs; Evans, Evans, & Evans, 2002; Wenglinksky, 1996). From the 1870s to 1960s, HBCUs graduated teachers, doctors, and other professionals to respond to the needs of a newly freed population and provide services to communities in a highly segregated context (Allen, Jewell, Griffin, & Wolf, 2007; Wenglinksky, 1996). Noted civil rights activist, such as W.E.B. DuBois, Martin Luther King, Jr., Ralph David Abernathy, Huey P. Newton, and Marion Wright Edelman attended HBCUs; thus, HBCUs became sites of political resistance and civil rights advocacy in the United States (Albritton, 2012; Douglas, 2012).

HBCUs, whether consciously or unconsciously, pursue a racial justice mission—decades of literature suggest they continue to offer social mobility to students who are primarily first-generation, economically disadvantaged, and ethnic minorities (Allen et al., 2007; Albritton, 2012; Douglas, 2012; Sydnor, Hawkins, & Edwards, 2010). Their undergraduate classrooms, more often, include students who do not meet the academic criteria to enter more “elite” institutions (Evans, Evans, & Evans, 2002). They have served as sites of resistance against segregation and racial oppression while struggling to sustain their mission in a racial climate filled with hostility, reduction in financial aid to low-income families, rising cost of tuition, and greater competition from HWIs (Douglas, 2012). Furthermore, HBCUs are linked to localities that face significant economic instability and disparate health and education conditions. As sites for racial justice, HBCUs and their surrounding locality, in theory, provide an ideal context for engaging community psychology practice (Albritton, 2012; Henderson & Wright, 2014; Sydnor, Hawkins & Edwards, 2010).

The Use of Narrative in Empowerment and Reflection

Narrative is a method used in empowerment and reflection (Nelson & Prilleltensky, 2005; Rappaport, 1995). It provides a story, creates visual imagery and affective response, and documents the learning process (Asselin, 2011; Connelly & Clandinin, 1990; Ollerenshaw & Creswell, 2002). Narratives have a rich tradition among African Americans in the United States. For example, Gates (1987) argued the origin of slave narratives became passages of freedom for African Americans. Used as a method of storytelling, slave narratives allowed people of African descent to exercise power and challenge racial injustice in the United States. The power of the narrative, retelling and restorying, became a tool to carve a path from slavery to freedom and construct new realities for African Americans (Gates, 1987). Narratives invoked emotion and visual imagery, allowing storytellers to engage in social action and empowerment (Connelly & Clandinin, 1990). The narrative illustrates the lived experience of individuals, generates new forms of knowledge, and can be an exercise of power among marginalized groups (Nelson & Prilleltensky, 2005; Rappaport, 1995).

Narratives can be reflective by a process of reunderstanding, which aims to reframe attitudes and beliefs from specific experiences and events (Asselin, 2011; Ollerenshaw & Creswell, 2002; Olshtain & Kupferberg, 1998). For instance, the reflective narrative allows the storyteller to critically examine his or her actions, feelings, and attitudes about an experience (Connelly & Clandinin, 1990; Nygren & Blom, 2001). In the course, the reflective narrative prompted undergraduate students to think about their attitudes and beliefs both prior to an experience or reading and afterwards. It became a tool to generate tension and resolution between former and developing beliefs (Nygren & Blom, 2001).

Similar to slave narratives, the reflective narrative can build our understanding of lives outside the dominant narrative and foster social action. The slave narratives were reflective—passages that demanded the United States and world to pay attention to injustices of slavery. Narratives are also relevant to community psychology because they illustrate developmental processes and draw pathways between the past and potential future (Rappaport, 1995). Narratives are a reflection of the past and engage a visioning process of what can be. Slave narratives illustrate the injustices of our past but they also presented a possible future, a time when African Americans would achieve justice and equality. We draw on the use of narratives in African American traditions and community psychology as methods of knowledge sharing, learning, and empowerment (Gates, 1987; Nelson & Prilleltensky, 2005; Ollerenshaw & Creswell, 2002; Rogers & Mosley, 2013).

The Scene: Winston-Salem State University and Waughtown

The undergraduate community psychology course is one of several courses listed under the Community, Health and Counseling Foundation in the Department of Psychological Sciences at Winston-Salem State University. The university is located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Founded in 1892 as a training school for African Americans, Winston-Salem State University now serves more than 5,000 undergraduate and graduate students; 71% of the population is female, 72% self-identify as African American, and about 66% receive the Federal Pell grant[1]. Service is an important thread in the fabric of the university; students perform a variety of service-oriented activities on and off campus. At the time of this work however, there were no clear indicators of the extent of community-engaged practice or research at the university. Moreover, the Department of Psychological Sciences did not offer any course integrating service learning or participatory research experiences to undergraduate students.

The S.G. Atkins Community Development Corporation (CDC) is an extension of Winston-Salem State University and works in partnership with the City of Winston-Salem. Located in the Waughtown neighborhood, the S.G. Atkins CDC aims to improve economic development, foster collaboration between the university and community, and serve as an incubator for small businesses. The Waughtown Neighborhood Revitalization Project was an initiative funded by the City of Winston-Salem for the S.G. Atkins CDC to engage local residents in identifying priorities for improving their locality and developing a plan of action for community change.

Waughtown is less than seven minutes away from the university and, at the time of the project, had an estimated population of more than 2,500 residents. The presence of the tobacco industry and manufacturing led to economic and population growth between the 1930s and 1950s; however, as more African American families moved in White residents moved out. In the 1990s, manufacturing jobs began leaving the city, which resulted in a significant portion of undereducated and unemployed residents in Waughtown. An increase in residents from Central and South America led to significant shifts in the population over the past decade. Today, Waughtown is considered one of the most diverse localities in the city of Winston-Salem; 80% of the population self-identify as an ethnic minority.

Waughtown faces significant social barriers. Only 31% of the adult population had an education post high school; the median household income in 2014 was $23,587 (compared to $43,665 for the city of Winston-Salem). About 21% of households in Waughtown are headed by single-females and about 62% of the children live in poverty (NeighborhoodScout, 2015). The state identified the two schools in Waughtown as high priority schools, indicating over 80% of students qualify under free or reduced-price lunch and less than 55% are performing at or above grade level on statewide exams (NC Department of Public Instruction, 2015). In spring 2015, the S.G. Atkins CDC collaborated with faculty from the Community-Based Participatory Research Learning Community to engage undergraduate students in the revitalization project. We reflect on this project.

The Actors

Our narratives are from two standpoints, faculty and undergraduate students, and reflect on the five foundational principles of community psychology practice. We aim to illustrate “praxis” in our work across the community psychology course and Waughtown Neighborhood Revitalization Project.

Faculty: Henderson

The course at Winston-Salem State University is one-semester and I have limited time with students. I decided to use the foundational principles (ie. ecological perspectives, empowerment, socio-cultural competence, community inclusion, and ethical and reflective practice) as topical areas because I believed they were critical to undergraduate students’ knowledge of community psychology and the most pragmatic.

In reflecting on her work and competencies, Langhout (2015) suggests our work in community psychology is driven by both heart and hand—deep held beliefs and affect towards reducing inequality and injustice. When I entered Winston-Salem State University there was a common story about HBCUs, these stories included “you will not be able to do research with the teaching load they give you” “the students are underprepared” and “they do not have resources or the infrastructure to…” This language reflects a deficit narrative and influences perception of HBCUs and the students within them (Evans, Evans, & Evans, 2002). I entered this space driven primarily by my passion to spread the doctrine of community psychology and infuse community engagement into the psychology paradigm. My presence in the university served as a point of activism in a context where undergraduate students primarily represent individuals from economically fragile, rural and urban communities, who are more often characterized by under-resourced K-12 public schools. I joined a learning community at the university, Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR), with the desire to develop community partnerships and collaborate with faculty on curriculum and research projects. Three faculty (from Urban Geography, Graphic Design, and Social Work) and I collaborated with the S. G. Atkins CDC to support development in Waughtown.

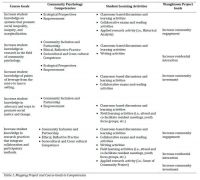

Using a modified version of curriculum mapping (Sarkisian & Taylor, 2013; Sarkisian et al., 2013), dialogue with faculty from the learning community led to aligning goals from the project with the course and competencies (see Table 1). I proceeded with designing the syllabus knowing very little of Waughtown. I was a faculty member who came on campus to teach, conduct my research, and never ventured on the Southeast side of town. I, like my undergraduate students, was going to learn about this rich community through the course.

Table 1 is available in the PDF and as an image below.

In the class, we modeled dimensions of socio-cultural diversity by challenging students’ notions of diversity beyond ethnicity and race. We discussed how dimensions of diversity grant access to resources and power. Some of the discussions centered on how education and ability allows students to access resources and power but gender may prevent them from gaining access to equal paying jobs. I designed the syllabus to challenge students to think about position, power, and privilege; it forced undergraduate students to examine their own biases. I wanted students to understand they would enter Waughtown from a standpoint of privilege and therefore carried perceptions that reinforced oppressive systems (e.g., people were poor because they choose to be poor). One student shared her thoughts on privilege in her reflection:

In class, we talked about the meaning of being privileged and what made people more "privileged" than others…Doing the assignment in class, it helped a lot of us realize where we fall when it comes to being privileged…I realized that I was considered to be extremely privileged although I don't feel like I am. I say this because growing up, we struggled a lot. There was a time where we lived in a house with no heat or lights and I had to watch my mother do everything she could to provide for us. Even today, she struggles but we've come a long way from where we used to be. I would say that I am a part of a middle class family and I've had many [more] opportunities than others.

Ecological perspectives were introduced to undergraduate students using the Kloos et al. (2012) textbook model, where they engaged in looking at issues from a multi-systems perspective. Students were required to identify how multiple systems and resource allocation influenced development and behavior and apply this to a neighborhood. Using Kelly’s (1986) ecological metaphor, I modified the historical analysis (Appendix A) activity used in political science education to engage students in identifying how economic and social forces drove change in Waughtown. We used maps of Waughtown provided by the S.G. Atkins CDC to generate course discussion on resources. Students were asked to think about challenges residents would encounter; maps identified schools, parks, as well as demographics of Waughtown (e.g., age, median income, ethnic composition, etc.). The maps challenged students’ preconceived notions about resources in Waughtown and proximity to the university. Matlock shared in her reflection:

It bothers me that our school and the S.G. Atkins CDC is so close and the students don’t even know there’s another community less than two minutes away…It saddens me how we’ve placed ourselves above the surrounding community to the point we don’t interact with them unless it’s for community service. To counteract our current mindset of being above; if students were to involve themselves in the community of Waughtown we could possibly [restore] Waughtown.

I fostered community inclusion and empowerment by requiring undergraduate students to engage course dialogue and work with residents from Waughtown. All of us, undergraduate students and I, attended meetings and various events at the S.G. Atkins CDC. We co-facilitated focus groups with residents and youth to frame challenges in Waughtown and envision a potential future. We discussed elements of community in the course (McMillan & Chavis, 1986) and talked about how these exist across localities, organizations, and institutions. I designed the sense of community video project (Appendix B) to give students an opportunity to identify assets and strengths in Waughtown; they worked in teams (3 to 4 students), and interacted with residents, youth, business owners, and agencies to think through their projects. Projects required undergraduate students to drive around Waughtown, meet with residents and business owners, and take pictures of landmarks or symbols that represented Waughtown’s identity. At the end of the spring semester, the S.G. Atkins CDC invited students to share their video projects with more than 125 residents to highlight assets and demonstrate a projected vision for the future.

Ethical and reflective practice was woven throughout the course experience. We engaged in discussions on the strengths and weaknesses of the revitalization project. Undergraduate students had to write reflections on selected readings and experiences. I discovered in their writing reflections cognitive shifts, tensions between their prior attitudes and beliefs about Waughtown. The undergraduate students were engaged in a discovery of their own agency as well as the capacity of residents in Waughtown, they ventured beyond the borders of the university and initiated efficacy towards community change (Henderson & Wright, 2014). I share their stories.

Undergraduate Students

Matlock

I enrolled in the Introduction to Community Psychology course in spring 2015. Prior to completing the course, I never thought about using multiple perspectives in research and was unaware of the term “community practice.” I remember the term “multiple perspectives” in an introductory course in Sociology. I had no idea Waughtown existed down the street from our university and I am not sure if many students who live on campus are aware of Waughtown. Our university emphasized community service to surrounding localities, but I do not think any of us ever ventured into Waughtown. Along the way, I discovered how to collaborate with residents in the research process.

Prior to the course, I had a belief that research only occurred by administering surveys to people. This is what we learn in our psychology paradigm, we have two sequenced courses of Research Methods and Statistics. In the community psychology course however, I discovered new ways to conduct research. I discovered how to include community members in the research process. I was able to see how community members gained control and participated in the process of creating change in their community. The sense of community project allowed us to use a process of storytelling, where members talked about issues affecting their community from their point of view. We collected their responses and tallied them. I went to community centers and schools to gain insight from youth and discovered what they wanted to see in Waughtown. We used a form of participatory action research by talking to residents and youth and asking them to envision an ideal community—we shared our findings with them and had them rank what was most important. This process became an important foundation in developing the neighborhood plan.

At one point in my life, I believed the problems facing many communities of color were primarily due to the residents in the community. Honestly, I did not think people cared about the condition of their communities until we watched The Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative documentary in class. In one of our meetings with residents at the S. G. Atkins CDC, some residents indicated they did not feel like their voice or their problems were important. At that moment, I realized the importance of residents feeling included and their role in building or rebuilding Waughtown. I no longer looked at community issues from the individual level because I gained an understanding of an ecological perspective. I gained an understanding of bi-directional movement across systems—the behavior of localities impact residents and residents can have the capacity to impact their locality. I know the important role resident engagement plays in driving community change.

This class alone transformed my thought process on the topic of community. This class opened my eyes to the concept of community psychology where I am able to practice the concepts of community inclusion, empowerment, and ecological perspectives to everyday experiences. Prior to this course, I never believed that I could inspire someone or even empower a person. I used to think empowerment came from professors, teachers, and anyone that was of higher status. However, I had the opportunity to facilitate sessions with residents and youth for the Waughtown project. Throughout this journey, I was able to unpack personal biases and fears I had of Waughtown. Even now, I use reflective practice to rethink what I am doing and how it relates to where I am going. I used to think justice demanded protesting but this course taught me there are others ways to address injustice. I reflect on these experiences because I aim to improve who I am and continue work in community building. In my opinion, after the course, I believe college students, at minimum, should be aware of their surrounding locality and find ways to build them up.

Clark

I began as a Social Work major prior to transferring into the Department of Psychological Sciences, so I knew a little about systems theory. Prior to taking the community psychology course, I never had a great concern about what was going on in the community, specifically Waughtown. The research conducted in the course helped me realize the bigger picture and design a plan of action for Waughtown to thrive. Having the opportunity to work with a team to develop an economic development plan for the community and provide assistance was a tremendous experience. Personally, I have never tried to make a difference in any community because I never believed the communities around Winston-Salem State were home. Yet, after working in Waughtown, I began to see people working together to change their community. One day, I visited a discount tire and auto shop in Waughtown for an oil change and had a brief conversation with the owner. He informed me that occasionally he helps provide food for the less fortunate in the community; he emphasized the importance of building up Waughtown and giving back. He was not aware of it on that day, but I gained much from that conversation. He helped me realize that I can have the power to make a difference; small changes can lead to larger change.

As a student on the economic development committee with the Waughtown project, I participated in generating ideas to address low employment and health with various residents and professionals. We were confronted with multiple ideas and thoughts. We had to think about cultural diversity and ways to adapt our ideas to represent the diverse residents in the area. As undergraduate students, we had to form partnerships with certain residents and leaders in the community in order to achieve a common goal. On the committee, I collaborated with two elders who lived in Waughtown on ways to strengthen businesses and residential homes. This experience changed me a bit; those elders challenged me to value the diversity of Waughtown—both young and old, African American and Hispanic.

Together, students, residents, and business owners co-facilitated the learning process while strengthening relationships between Waughtown and the university. We threw plenty of ideas around in class on how to solve certain problems, such as transportation and accessing medical support, but we needed the leaders in Waughtown. In the meetings, residents shared their ideas and vision for Waughtown. We were able to work together in prioritizing short-term versus long-term goals and points of advocacy. Engaging in the locality allowed residents to see us as partners and establish trust. We needed to communicate to the residents that we cared about them and their well-being. We aimed to recognize the resources and assets in Waughtown and make sure these residents became equal in the process. I was able to see the value in our work with Waughtown residents by sharing the process of identifying goals and developing plans of action.

Garrett

I took the community psychology course entering my senior year at Winston-Salem State University. Prior to the community psychology course, I had no knowledge of ecological perspectives. I also never considered the myriad ways systems can influence people and their decision making. The course broadened my perspective on how problems emerge in communities. It broadened my perspective on how to leverage systems change. Prior to taking this class and reading about points of leverage, I associated the term leverage to business and it had a negative connotation. To me, it meant taking advantage of someone or exploiting him or her for your own benefit. I discovered, points of leverage are where we choose to enter the system and address change. The ecological perspective challenged us to understand Waughtown from the perspective of changes over time. We were challenged with thinking about how to increase collectivism and healing in the community. I have been thinking constantly about how I could use this knowledge in my hometown, Washington D.C. I believe that I can have a greater impact on driving change by focusing on how culture and assets build individuals rather than complaining about the high crime rate and poverty.

Prior to the community psychology course, I used reflective thinking as a way to challenge my assumptions and beliefs. In the course, we used reflective thinking to reflect on our work with Waughtown and examine challenges. Before we had the opportunity to enter Waughtown, we participated in a number of discussions and class exercises on ethical behavior and reflective practice. We also moved away from emphasizing concepts like sample size, experiment, and focused on participatory and community research. As participants, we noticed how input from residents was challenging. We did not have large representation among the Hispanic community and some residents were hesitant about trusting the revitalization plan. In the end, I realized how important it is to give opportunities and provide spaces for residents to engage in problem solving.

Volunteering in Waughtown shifted my perspective of community. I originally perceived Waughtown was like any other broken community, a place where residents demonstrated little hope in changing their circumstances or lacked positive relationships with each other. I did not feel I would find a sense of community in Waughtown. I volunteered at a community garden event and in resident meetings, talked with residents, and I began to witness this sense of community in Waughtown. Waughtown had residents who cared about the relationships they have with each other and wanted to change—this will forever remain with me. I cannot take everything at face value, every community is diverse, but there are always residents who care and believe they can make their locality better. I think there is plenty of hope for Waughtown if we continue to find ways to encourage and integrate the voices of residents and undergraduate students.

In the community psychology class, I believe we all experienced a sense of empowerment because we realized our roles in advocating for Waughtown. We often look to others who have higher rank or more authority to create change but this course demonstrated power is fluid and lies within the smallest individual, both students and residents. We encouraged the residents of Waughtown to use their points of privilege and voices in community change. After completing the course, I stepped outside my comfort zone; I became a mentor to first-year students, and completed an internship with the American Psychological Association. I made it a point to find ways to encourage others and give back.

Faculty: Henderson

Prilleltensky (2001) argues praxis is cyclical and defined by constant reflection and action. I reenter our narrative to reflect on challenges in applying competencies in Waughtown and within HBCUs. First, trust emerged as a central theme among students and residents in Waughtown. Populations that experience constant disruptions or share a history of unethical research practices (e.g., Tuskegee Experiment) are accustomed to people entering and exiting their localities. They experience the “let downs,” often exploited for their resources or always “talking” but rarely moving to action. Trusting the project would lead to change was challenging for undergraduate students and residents. One student wrote in her reflection:

It is clear that many of the citizens in Waughtown want change, but it is questionable whether that change will even happen. At the meeting, the concerns of local residents, landlords and business owners were written down but they were just talked about. The meeting lacked two key elements that would have maybe helped to advance the process of improvement. Those two element are; more input from the residents and an actual plan to address the issues. Currently the Waughtown community is in the contemplation stage, but the residents want action…Although multiple meetings have occurred within Waughtown, not much has happened. This cycle can lead to discouragement [among] residents and business owners... I remember speaking to one of the men and he said, “We keep having these meetings, and we talk about all of the problems, but nothing is going to change.” Many of the citizens know that even though they meet and discuss problems, nothing will change in their community.

This was one of the most difficult pieces to translate to both undergraduate students and residents. How do we get communities and populations to believe in change when they have experienced a history of exploitation and marginalization? I, in my limited experience, did not have the answer but reflect back on Langhout (2015). I reminded the undergraduate students, community psychologists are driven by a high sense of optimism and a deep belief that we can achieve justice. Our involvement in Waughtown did not center on changing their problems but rather granting residents the power to identify their challenges and collaborate with a university and community development group to design an action plan in order to map attainable short and long-term goals.

Second, we must understand our work rarely produces immediate results and requires investing time beyond our duties as faculty, students, and practitioners. In a university primarily driven by teaching and, at the time, one that did not quite understand community psychology, I had to sacrifice time. I questioned the amount of time committed to this project. I was teaching a Research Methods and Statistics course with two labs and had a family. The students were attending meetings outside the normal day and on weekends; many of the undergraduate students in the course had jobs and families. A few of them drifted in and out of the course; largely due to family challenges and other personal issues. Our stakeholders wanted immediate results and, on occasion, were unwilling to understand the developmental process of change—specifically change at the locality level. Furthermore, the students knew they were only in this space temporarily and their work with Waughtown was limited. I believe this challenges our ability to see lasting benefits of our labor, particularly for students who are not in an undergraduate community psychology program and only commit one semester.

Finally, I want to reflect on our challenges in community inclusion and participatory processes. Our course did not drive the project and we had little control over the involvement of residents in the planning process. Early in our project, we realized youth and Hispanic residents were absent in the planning process. I constantly reminded the planning committee to think about underrepresented groups in our meetings and had to rely on my experience with youth to facilitate youth engagement. I developed an activity to use in youth focus groups, which allowed youth to identify five wishes for their community; we tabulated the results and shared this information with the committee. We used these results to convince the planning committee youth could provide relevant perspectives. Unfortunately, it was more challenging to engage adult Hispanic residents. No one in the course was fluent in Spanish. We encountered not only language but also trust barriers. On the peripheral, we were unaware of the power of Hispanic pastors in Waughtown and missed outreach to this community. Later in the project, a Hispanic pastor informed us some residents feared the presence of law enforcement at meetings and would not attend. At times, it appeared as if we were all in a cloud of obscurity when it came to engaging Hispanic residents. I believe equitable inclusion was difficult given the diversity of Waughtown; we captured about 10% of the residents’ perspective in the planning project. Inclusion of more residents would require a team member or undergraduate students who were fluent in Spanish and able to work across various groups in Waughtown.

Conclusion

Legitimacy of community psychology is linked to challenges HBCUs and our communities encounter in the United States. We all struggle to tell our story and express our worth and value. We encounter social limitations due to histories of marginalization and distrust. As agents of social and racial justice, we push against the limitations and emerge out of the shadows. We acknowledge the inequalities in Waughtown and the residents struggle for community change. We recognize the social inequalities that led us into HBCUs, yet we refuse to accept them. Garrett wrote in one of his reflections:

The course taught us that social equality and equity are driving principles in community psychology and should be applied everywhere. This principle is highly relevant to me as a young black man in America, a country that historically imposes injustices against my demographic…I would like to think that it takes it a step further and it gives you the power to recognize inequalities directed towards you and still be able to recognize your worth at the same time. It helps you realize that oppression is both a state and a process and that you do not have to accept those standards that oppress you.

Our stories demonstrate the “praxis” of community psychology competencies; praxis empowered undergraduate students and residents to gage their assets and strengths. Using competencies in "praxis" led to our collective worth and power despite living in a context that ties notions of worth and value to color, class, etc. Praxis challenged us to grapple with transforming theory into practice and we continue to learn. We add our voices to the dialogue and understand we still have a long journey ahead.

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank the S.G. Atkins Community Development Corporation, Carol Davis, Drs. Russ Smith, Tammy Evans, and Paul Kron with the Piedmont Triad Regional Council. We would like to acknowledge the residents of Waughtown, staff, and everyone who participated in organizing the Waughtown Neighborhood Revitalization Project. We would also like to acknowledge all of the undergraduate students who participated in the Introduction to Community Psychology course at Winston-Salem State University.

NOTE

[1] The Federal Pell Grant is funding support awarded to students who have never received a Bachelor’s degree and demonstrate financial need.

References

Albritton, T. J. (2012). Educating our own: The historical legacy of HBCUs and their relevance for educating a new generation of leaders. Urban Review, 44, 311-331. doi: 10.1007/s11256-012-0202-9

Allen, W. R., Jewell, J. O., Griffin, K. A., & Wolf, D. S. (2007). Historically Black colleges and universities: Honoring the past, engaging the present, touching the future. The Journal of Negro Education, 76, 263-280.

Asselin, M. E. (2011). Reflective narrative: A tool for learning through practice. Journal for Nurses in Professional Development, 27(1), 2-6. doi: 10.1097/NND.0b013e3181b1ba1a

Christians, J. C. (2014). Understanding the Black Flame and multigenerational education trauma: Toward a theory of dehumanization of Black students. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books

Connelly, F. M., & Clandinin, D. J. (1990). Stories of experience and narrative inquiry. Educational Researcher, 19(5), 2-14.

Dalton, J. & Wolfe, S. (2012). Competencies for community psychology practice: Society for Community Research and Action draft August 15, 2012. The Community Psychologist. Retrieved from http://www.scra27.org.

DeGruy, J. (2005). Post traumatic slave syndrome; America’s legacy of enduring injury and healing. Portland, OR: Uptone Press.

Douglas, T. M. O. (2012). HBCUs as sites of resistance: The malignity of materialism, western masculinity, and spiritual malefaction. Urban Review, 44, 378-400. doi: 10.1007/s11256-012-0198-1

DuBois, W. E. B. (1903). Of Mr. Booker T. Washington and others. Retrieved from http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/40/.

Evans, A. L., Evans, V., & Evans, A. M. (2002). Historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs). Education, 123 (1), 3-17.

Gates, H. L. (1987). The classic slave narratives. New York, NY: Signet.

Glaeser, E., & Vigdor, J. (2012). The end of the segregated century: Racial separation in America’s neighborhoods, 1890-2010. Manhattan Institute for Policy Research, No. 66.

Henderson, D. X. (in press). Community engagement in an undergraduate course in psychology at an HBCU. Teaching of Psychology.

Henderson, D. X., & Wright, M. (2015). Getting students to “go out and make a change:” Promoting dimensions of global citizenship and social justice in an undergraduate course. Journal of Contemporary Issues in Higher Education, 1, 14-29.

Hughes, L. (1934). Cowards from the colleges: An essay. The Crisis, 41. 227-228.

Kelly, J. G. (1986). Context and process: An ecological view of the interdependence of practice and research. American Journal of Community Psychology, 14(6), 581-589. doi:10.1007/BF00931335

Kloos, B., Hill, J., Thomas, E., Wandersman, A., Elias, M., & Dalton, J. H. (2012). Community psychology: Linking individuals and communities (3rd Ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Langhout, R. D. (2015). Considering community psychology competencies: A love letter to budding scholar-activists who wonder if they have what it takes. American Journal of Community Psychology, 55(3), 266-278.

McMillan, D.W., & Chavis, D.M. (1986). Sense of community: A definition and theory. American Journal of Community Psychology, 14(1), 6-23.

NC Department of Public Instruction. (2015). ABCs of public education. Retrieved from http://www.ncdpi.org

NeighborhoodScout. (2015). Waughtown. Retrieved from http://www.neighborhoodscout.com

Nelson, G., & Prilleltensky, I. (2005). Community Psychology: In pursuit of liberation and well-being. New York, NY: Palgrave MacMillan.

Nygren, L., & Blom, B. (2001). Analysis of short reflective narratives: A method for the study of knowledge in social workers' actions. Qualitative Research, 1(3), 369-384. doi:10.1177/146879410100100306

Ollerenshaw, J. & Creswell, J. W. (2002). Narrative research: A comparison of two restorying data analysis approaches. Qualitative Inquiry, 8 (3), 329-347. doi: 10.1177/10778004008003008

Prilleltensky, I. (2001). Value-based praxis in community psychology: Moving toward social justice and social action. American Journal of Community Psychology, 29(5), 747-778.

Rappaport, J. (1995). Empowerment meets narrative: Listening to stories and creating settings. American Journal of Community Psychology, 23(5), 795-807.

Rogers, R., & Mosley Wetzel, M. (2013). Designing critical literacy education through critical discourse analysis: Pedagogical and research tools for teacher researchers. New York, NY: Routledge.

Sarkisian, G. V., & Taylor, S. (2013). A learning journey I: Curriculum mapping as a tool to assess and integrate Community Psychology practice competencies in graduate education programs. Global Journal of Community Psychology Practice, 4 (4). Retrieved from http://www.gjcpp.org/en/

Sarkisian, G. V., Saleem, M. A., Simpkin, J., Weidenbacher, A., Bartko, N., & Taylor, S. (2013). A learning journey II: Learned course maps as a basis to explore how students learned Community Psychology practice competencies in a community coalition-building course. Global Journal of Community Psychology Practice, 4(4). Retrieved from http://www.gjcpp.org/.

Sydnor, K. D., Hawkins, A. S., & Edwards, L. V. (2010). Expanding research opportunities: Making the argument for the fit between HBCUs and community-based participatory research. The Journal of Negro Education, 79(1), 79-86.

Wenglinsky, H. (1996). The educational justification of Historically Black Colleges and Universities: A policy response to the U.S. Supreme Court. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 18 (1), 91-103.

Woodson, C. G. (1933). The mis-education of the Negro. Hampton, VA: U.B. & U.S. Communication Systems.

Wolfe, S. M. (2014). The application of community psychology practice competencies to reduce health disparities. American Journal of Community Psychology, 53(1-2), 231-4.

Wolfe, S. M., Chien-Scott, V., & Jimenez, T. R. (2013). Community psychology practice competencies: A global perspective. Global Journal of Community Psychology Practice, 4 (4), 1-9. Retrieved from http://www.gjcpp.org/en/

Appendix A. Historical Analysis Activity-Introduction to Community Psychology

HISTORICAL ANALYSIS (50 Points): Historical analysis is less a separate analytical framework or approach than it is an element that should be present in any analysis of a community. Observing and analyzing changes over time is essential to understanding the underpinnings of a community and its challenges. We cannot understand our present without understanding our past. And we cannot fully imagine change without a sense of how a community has changed over time (Cultural Politics, 2014). This paper (4-6 pages) requires students to examine the history of the Waughtown community as it relates to neighborhood changes, populations, etc. You should use DIGITAL FORSYTH and the O’Kelly Library Archives as sources of information. You can also use Google Search or other search engine to find articles, blogs, community forums, etc. that may have existed. In your final paper, you should have the following:

For example:

Waughtown, 1950

In 1952, Waughtown began to see a shift in the people who comprised the working class community. One the major steel plants, Colby, was shut down and it left a number of people without jobs…

Appendix B. Sense of Community Activity-Introduction to Community Psychology

SENSE OF COMMUNITY PROJECT (100 Points): McMillan and Chavis (1986) describe a sense of community in four elements: membership, influence, integration and fulfillment of needs, and shared emotional connection. Using these elements, you will prepare an audiovisual piece that defines how Waughtown displays a sense of community and submit a paper. This is a major assignment and should not be approached lightly. The goal of this activity is to provide with an opportunity to develop a narrative and visual project that frames the Waughtown Community Development project. Final submission of the writing assignment should be double-spaced, 12-font, Times New Roman, Arial, or Calibri. This assignment will ask that you collect historical and current data and information on Waughtown using a variety of sources (e.g., journal articles, blog post, newspapers, community meetings, and interviews). In this assignment you will be required to:

The final paper should have the following headings (50 Points):

The final presentation should be a representation of the paper and display the four elements of a “sense of community” provided from the paper (50 Points). REMEMBER, WORK SMARTER NOT HARDER. This project will require you to:

Appendix C. Five Wishes for My Community-Youth Activity-Introduction to Community Psychology

Five Wishes for My Community

A youth facilitated activity designed to gain perspectives of community needs in Waughtown, Winston-Salem, NC. In order to complete this activity, you will need at least one facilitator for every 5-7 youth.

Age Range

Supplies

Directions

Appendix D. Sense of Community Video-Introduction to Community Psychology

Download the PDF version to access complete article, including Tables, Figures, and Appendices

Table 1: Mapping Project and Course Goals to Competencies |

Dawn X. Henderson, Jameika R. Matlock, DayQuan Garrett, Christopher Clark

Dawn X. Henderson, Jameika R. Matlock, DayQuan Garrett, Christopher Clark

Dawn X. Henderson, PhD, received her training in community psychology from North Carolina State University. She uses pedagogy to engage in empowerment and social and racial justice work with undergraduate students. She served as an Assistant Professor in the Department of Psychological Sciences at Winston-Salem State University.

Jameika R. Matlock received a Bachelor of Arts degree in Psychology from Winston-Salem State University. She is currently pursuing a Master of Science degree in Community Psychology at Florida A&M University.

DayQuan Garrett received a Bachelor of Arts degree in Psychology from Winston-Salem State University. He currently works in the U.S. Department of Personnel Management in Washington, DC and aims to pursue a PhD in Community Psychology.

Christopher Clark received a Bachelor of Arts degree in Psychology from Winston-Salem State University. He currently volunteers as a firefighter and plans to pursue a Master of Science degree in Marriage and Family Counseling.

agregar comentario

![]() Descargue la versión en PDF para acceder al artículo completo, incluyendo tablas y figuras.

Descargue la versión en PDF para acceder al artículo completo, incluyendo tablas y figuras.

palabras clave: HBCUs, community psychology, competencies, undergraduate students