Theories are a fundamental part of research. They provide guidance for the development of research questions and testable hypotheses as well as inform study methods and designs. However, in this issue, Jason, Stevens, Ram, Miller, Beasley, and Gleason (2016) raise important questions including: Are prominent “theories” in community psychology really theories? How useful are these “theories” for developing specific predictions and testable hypotheses? And, how can the field continue to develop and test theories that promote its agenda of social change? To answer these questions, Jason et al. (2016) identify and evaluate three “prominent theories” in community psychology – the ecological perspective (Kelly, 1968), psychological sense of community theory (Sarason, 1974), and empowerment (Rappaport, 1981). Based on their evaluation, they “conclude that community psychology theories have tended to function as frameworks” (p. 2). That is, these “theories” provide general guidance for what elements to study but fall short of offering specific predictions about the relationships between these elements. Jason et al (2016) conclude that the lack of predictive and explanatory theories in community psychology hinders progress in both the research development of explanatory mechanisms of social change as well as practice initiatives to promote social change. However, despite these major contributions, in this response I contend that the “prominent theories” identified by Jason et al (2016) were never intended to be theories in the first place. While Jason et al (2016) are right to call for more application of theory in community psychology, I provide a more optimistic view of the field’s current use of theory.

Download the PDF version to access the complete article, including tables and figures.

Theories are a fundamental part of research. They provide guidance for the development of research questions and testable hypotheses as well as inform study methods and designs. However, in this issue, Jason, Stevens, Ram, Miller, Beasley, and Gleason (2016) raise important questions including: Are prominent “theories” in community psychology really theories? How useful are these “theories” for developing specific predictions and testable hypotheses? And, how can the field continue to develop and test theories that promote its agenda of social change? To answer these questions, Jason et al. (2016) identify and evaluate three “prominent theories” in community psychology – the ecological perspective (Kelly, 1968), psychological sense of community theory (Sarason, 1974), and empowerment (Rappaport, 1981). Based on their evaluation, they “conclude that community psychology theories have tended to function as frameworks” (p. 2). That is, these “theories” provide general guidance for what elements to study but fall short of offering specific predictions about the relationships between these elements. Jason et al (2016) conclude that the lack of predictive and explanatory theories in community psychology hinders progress in both the research development of explanatory mechanisms of social change as well as practice initiatives to promote social change.

There are several major contributions of this paper. First, Jason et al (2016) should be commended for raising a much-needed conversation on the importance of theoretical development in the field of community psychology. Second, Jason et al (2016) contribute to the field of community psychology by clearly defining the roles of frameworks and theories in the research process. Third, Jason et al (2016) highlight the importance of theory for meeting the practice goals of our field. In order to alter community contexts in ways that create positive social change, we must have good theories that provide explanatory mechanisms to inform intervention.

However, despite these major contributions, in this response I contend that the “prominent theories” identified by Jason et al (2016) were never intended to be theories in the first place. Instead, the ecological perspective was always intended as a framework and both psychological sense of community and empowerment are more appropriately described as phenomena of interest in the field of community psychology. If we dig deeper into the community psychology literature, many specific theories have been applied. While Jason et al (2016) are right to call for more application of theory in community psychology, I provide a more optimistic view of the field’s current use of theory.

Phenomenon of Interest, Framework, or Theory?

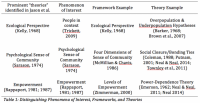

Jason et al (2016) draw a clear distinction between the role of theories and frameworks in research. The goal of frameworks is broad description, and as Jason et al (2016) note, a framework “informs researchers of the types of elements that are considered important avenues of investigation” (p. 8). Theories are narrower and can be conceptualized as nested within frameworks. The goal of theories is “describing, explaining, and predicting phenomena” (Jason et al., 2016, p. 4). More specifically, the goal of community psychology theory is to identify “what specific aspects of context influence what specific aspects of individuals” and to articulate the mechanisms by which this influence occurs (Jason et al., 2016, p. 35). This distinction between frameworks and theories is helpful. However, although implicit in their conversation, Jason and colleagues (2016) did not explicitly note what ties a framework and a theory together: a common phenomenon of interest. Phenomena of interest are broader than either frameworks or theories. Indeed, if theories are nested within frameworks, then frameworks are nested within phenomena of interest. As defined by Rappaport (1987), phenomena of interest are “what we want our research to understand, predict, explain, or describe” (p. 129). Frameworks seek to describe phenomena of interest while theories seek to predict or explain them. While Jason et al (2016) argues that common “theories” in community psychology are really frameworks, I suggest here that these “theories” were never intended to be theories in the first place. Instead, some (like the ecological perspective) were always intended to be frameworks while others (like psychological sense of community and empowerment) are phenomena of interest. Moreover, community psychologists have applied theories to help explain these frameworks and phenomena of interest (see Table 1 for examples).

Table 1: Distinguishing Phenomena of Interest, Frameworks, and Theories

Ecological theory

Jason et al. (2016) start their evaluation of “theories” in community psychology with the four principles of Kelly’s (1968) ecological perspective: interdependence, cycling of resources, adaptation, and succession. While they describe the ecological perspective as focused on “how people become effective and adaptive in different social environments” (Jason et al., 2016, p. 8), the phenomenon of interest is actually a bit broader. As stated by Trickett (2009), “the ecological perspective provides a framework for understanding people in community context and the community context itself.” Like Jason et al (2016), Trickett (2009) identifies the ecological perspective as a framework rather than a predictive theory. This framework keeps company with a number of other frameworks used in community psychology to understand people in context such as Tseng and Seidman’s (2007) systems framework for understanding social settings or Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) ecological systems framework.

If we start with the broader phenomenon of interest that the ecological perspective is trying to explain – people in community context – we do not need to look far to find examples where predictive theories have been applied. For instance, in his overpopulation and underpopulation hypotheses, Barker (1968) offered a theory about the relationship between the number of members in a setting, the number of roles in a setting, and member participation in that setting. In overpopulated settings where the number of members exceeds the number of roles, members are predicted to participate less in the setting. In underpopulated settings where the number of roles exceeds the number of members, members are predicted to participate more in the setting. These hypotheses have been tested in the community psychology literature, including recently within the context of consumer-run organizations by Brown, Shepard, Wituk, and Meissen (2007).

Psychological sense of community

Jason et al (2016) next evaluate Sarason’s (1973) psychological sense of community as a potential “theory” in community psychology. However, others have described psychological sense of community as a phenomenon of interest for community psychology (e.g., Riger, 1993). Indeed, akin to Rappaport’s (1981) definition of phenomenon of interest, psychological sense of community describes a feeling that individuals experience (e.g., interdependence with the community) that community psychologists would like to explain. In the community psychology literature, frameworks have been developed to help specify the dimensions or elements of psychological sense of community to which community psychologists should attend. For example, although McMillan and Chavis’ (1986) describe their four dimensions of sense of community as a theory, these dimensions are outlined with the primary goal of advancing community psychologists’ ability to operationalize and explore this phenomenon of interest. These dimensions could accurately be described as a framework that has informed the measurement of sense of community (e.g., Peterson, Speer, & McMillian, 2008).

Beyond frameworks that inform the measurement of sense of community, theories can help explain the mechanisms by which individuals come to experience a sense of community. In particular, theories from the social capital literature on the role of network closure (e.g., Coleman, 1988) or bonding ties (e.g., Putnam, 2001) suggest that psychological sense of community occurs when individuals form tightly-knit, within group relationships (Neal, 2015). These theories provide testable hypotheses that individuals who are situated in closed networks where everyone knows each other are more likely to experience high levels of psychological sense of community. Community psychologists have begun to apply these theories in discussions of psychological sense of community (e.g., Neal & Neal, 2014; Townley, Kloos, Green, & Franco, 2011) although empirical tests are still needed.

Empowerment

Jason et al (2016) also evaluated empowerment as a potential “theory” in community psychology. However, from the onset, Rappaport (1987) was clear that he viewed empowerment as a phenomenon of interest for community psychology, not a theory. In his own words: “A proper focus of theory for Community Psychology can be summarized, in a word, as empowerment. Put in its simplest terms, empowerment is the name I give to the entire class of phenomena that we want our research to understand, predict, explain, or describe” (Rappaport, 1987, p. 129). He then goes on to explore possible frameworks and theories that might address empowerment. Since Rappaport (1981, 1987) declared empowerment as a significant phenomenon of interest for community psychology, others have developed frameworks to describe this phenomenon. For example, Zimmerman (2000) delineates empowerment into empowering processes (i.e., activities that promote empowerment) and empowered outcomes (i.e., evidence of empowerment). Moreover, he describes how empowering processes and empowered outcomes can be explored at the individual, organizational, and community levels.

Beyond these general frameworks, community psychologists have offered predictive theories for how to facilitate both empowering processes and empowered outcomes. For example, Neal and Neal (2011) employed social exchange theory – specifically Emerson’s (1962) power-dependence theory – to clarify the role of power in empowerment and to make predictions about when individuals are most likely to experience power over resources (a common hallmark of empowerment, see Riger, 1993). This theory suggests that an individual’s power over resources (and consequently, empowerment) can be predicted by two things: (1) Does the individual have resources that others in his/her network desire? and (2) Within a resource exchange network, how many sources do others have for this desired resource? When individuals have a resource that others desire and there are few other sources for this resource, they are predicted to experience higher levels of empowerment. Moreover, Neal (2014) recently extended this theoretical work to consider how power-dependence theory could be applied to understand and predict empowering settings.

Next Steps for Theory in Community Psychology Research and Practice

If we first specify the phenomena of interest in our field (i.e., people in context, psychological sense of community, and empowerment), it is possible to dig just a bit deeper into the community psychology literature and locate the application of specific theories. This implies that the state of theory in community psychology may not be as dire as Jason et al (2016) suggest. However, the conversation started by Jason et al (2016) is still critical and offers important next steps for research and practice in community psychology. First, it is important for community psychologists to consciously distinguish between phenomena of interest, frameworks, and theories. Each plays a specific role in informing our research and practice. Phenomena of interest provide a focus for our work while frameworks help refine and describe this focus. Theories offer the unique ability to predict associations between relevant constructs and to provide explanatory mechanisms for these associations.

Second, as Jason et al (2016) argue, it is important to ensure that we intentionally move beyond applying frameworks to the application of theory in our research and practice. This application of theory is essential for explaining and predicting phenomena of interest. In the cases described in this reaction piece, community psychologists have applied predictive theories from other disciplines including environmental psychology (e.g., Barker, 1968) and sociology (e.g., Coleman, 1988; Emerson, 1962). Drawing on the contributions of other fields is appropriate given the interdisciplinary nature of our field (Bennett, Anderson, Cooper, Hassol, Klein, & Rosenblum, 1965), and community psychologists should carefully explore predictive theories developed in other disciplines that might help explain key phenomena of interest. However, as noted by Jason et al (2016), community psychologists should also consider opportunities to develop specific theories when there is a void in the interdisciplinary literature. If we take deliberate steps to include theory in our work, we stand a better chance at building better explanations of the phenomena of interest at the heart of community psychology.

References

Barker, R.G. (1968). Ecological psychology: Concepts and methods for studying the environment of human behavior (pp. 5-34). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Bennett, C.C., Anderson, L.S., Cooper, S., Hassol, L., Klein, D.C., & Rosenblum, G. (1966). Community psychology: A report of the Boston Conference on the education of psychologists for Community Mental Health (pp. 1-30). Boston: Boston University.

Brown, L.D., Shepard, M.D., Wituk, S.A., & Meissen, G. (2007). How settings change people: Applying behavior setting theory to consumer-run organizations. Journal of Community Psychology, 35, 399-416. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20155.

Emerson, R.M. (1962). Power-dependence relations. American Sociological Review, 27, 31-41.

Kelly, J.G. (1968). Towards an ecological conception of preventive interventions. In J.W. Carter, Jr. (Ed.), Research contributions from psychology to community mental health (pp. 75-99). New York: Behavioral Publications.

Jason, L.A., Stevens, E., Ram, D., Miller, S.A., Beasley, C.R., & Gleason, K. (2016). Theories in the field of community psychology. Global Journal of Community Psychology Practice.

McMillan, D. W., & Chavis, D. M. (1986). Sense of community: A definition and theory. Journal of community psychology, 14, 6-23.

Neal, J.W. (2014). Exploring empowerment in settings: Mapping distributions of network power. American Journal of Community Psychology, 53(3/4), 394-406. doi:10.1007/s10464-013-9609-z.

Neal, J.W., & Neal, Z.P. (2011). Power as a structural phenomenon. American Journal of Community Psychology, 48, 157-167. doi:10.1007/s10464-010-9356-3.

Neal, Z.P. (2015). Making big communities small: Using network science to understand the ecological and behavioral requirements for community social capital. American Journal of Community Psychology, 55, 369-380. doi: 10.1007/s10464-015-9720-4.

Peterson, N.A., Speer, P.W., & McMillan, D. (2008). Validation of a brief sense of community scale: Confirmation of the principal theory of sense of community. Journal of Community Psychology, 36, 61-73. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20217.

Putnam, R.D. (2001). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

Rappaport, J. (1981). In praise of paradox: A social policy of empowerment over prevention. American Journal of Community Psychology, 9, 1-25.

Rappaport, J. (1987). Terms of empowerment/exemplars of prevention: Toward a theory for community psychology. American Journal of Community Psychology, 15, 121-148.

Riger, S. (1993). What’s wrong with empowerment. American Journal of Community Psychology, 21, 279-292.

Sarason, S. B. (1974). The psychological sense of community; prospects for a community psychology. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Townley, G., Kloos, B., Green, E.P., & Franco, M.M. (2011). Reconcilable differences? Human diversity, cultural relativity, and sense of community. American Journal of Community Psychology, 47, 69-85. doi:10.1007/s10464-010-9379-9.

Trickett, E.J. (2009). Community psychology: Individuals and interventions in community context. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 395-419. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163517.

Zimmerman, M.A. (2000). Empowerment theory: Psychological, organizational, and community levels of analysis. In J. Rappaport & E. Seidman (Eds.) Handbook of community psychology (pp. 43-63). New York: Plenum

Table 1: Distinguishing Phenomena of Interest, Frameworks, and Theories |

Jennifer Watling Neal

Jennifer Watling Neal

Jennifer Watling Neal, Ph.D. is an associate professor of Community Psychology at Michigan State University. Her research and practice has focused on applying social network theories and methods to explore the dissemination of complex school-based interventions and to understand the contextual influences of schools and classrooms on children’s social behaviors. She has published theoretical work focused on applying social networks to advance empowerment frameworks and the ecological systems framework. She is also interested in the advancement of social network data collection and analytic methodologies in the field of community psychology. Jennifer received the 2016 Society for Community Research and Action Early Career Award in recognition of this work.

agregar comentario

![]() Descargue la versión en PDF para acceder al artículo completo, incluyendo tablas y figuras.

Descargue la versión en PDF para acceder al artículo completo, incluyendo tablas y figuras.

palabras clave: Theory, Science, Community Psychology, Framework