Ashlee D. Lien, Justin P. Greenleaf, Michael K. Lemke, Sharon M. Hakim, Nathan P. Swink, Rosemary Wright, and Greg Meissen

Community Psychology Practice and Research Collaborative, and Community Psychology Doctoral Program, Wichita State University, Wichita KS, USA

Even among people who know and have seen the value of logic models, the term can “strike fear into the hearts” of experienced community psychologists and veteran non-profit staff and board members alike. Add the phrase “outcome-based planning” and you are likely to energize those you are working with to run as fast as possible for the door. Such technical terms may confuse and intimidate community members and grassroots partners who are the foundation of the practice of community psychology. At the same time, organizations can benefit from time spent on outcome-based planning, especially in developing a well-conceived logic model.

Several well-established logic model guides are available, including those developed by the W.K. Kellogg Foundation, the Centers for Disease Control, the United Way, and the Community Toolbox. These complex guides, while used successfully for organizational planning and grant proposals, can be inaccessible to community partners due to technical language and the complicated nature of the process.

As community psychologists it is important to meet people and organizations where they are. By following this principle, we took the traditional logic model approach and translated it into a less daunting process. We call our approach the Tearless Logic Model. It breaks down the logic model process into a series of manageable, jargon-free questions. In fact, we do not even use the terms logic model, outcomes, outputs, or inputs until we have completed this energizing activity. We believe that through this process, organizations and community-based groups can receive the benefits of completing a logic model process without the intimidation factor.

Tearless Logic Model

Having used a number of the highly developed logic model approaches and formats in writing federal and foundation grants, we found ourselves failing miserably when we attempted to use these models collaboratively with community partners. We knew that we needed to try a new approach as we prepared to help a youth-serving organization develop a logic model with a group that included many high school age leaders. Instead of using a traditional approach, we tried a facilitated approach with an emphasis on visioning, grounded in appreciative inquiry and using common language. Our session was wildly successful, producing not only an excellent logic model for the organization, but also a lot of excitement in two hours instead of the four hours we had anticipated. We refined the process we used with the youth to create a tool which can be easily customized to fit the needs of different groups.

Audience

The Tearless Logic Model can be used most appropriately with almost any audience but is especially intended for use with community-based groups, coalitions, faith-based organizations, and smaller nonprofits. We have also used it successfully with government offices, established social service agencies, and even researchers familiar with logic models. This approach “levels the playing field” in terms of experience with strategic planning, research, and grant writing within a group, allowing unusual voices of service recipients, youth, and community members to have appropriately greater impact.

Context

The Tearless Logic Model is best implemented as a facilitated session that walks a broad and representative group of stakeholders through the process one step at a time. Finding a facility in which a “safe space” can be created for the group is helpful; a meeting room at a neighborhood center or in a church basement seems to work better than a corporate conference room or in the seminar room of the Psychology Department at a university.

Using the Tearless Logic Model

Materials

A small number of materials are necessary to lead a group through the Tearless Logic Model process:

Preparation

Preparation and setup for this model are quite easy. First, it is necessary to find an appropriate space in which to hold the logic model development session. As mentioned earlier, this should be a “safe space,” where individuals feel free to express their opinions and insights. Collaborative efforts that bring together many stakeholders require a safe space where those with different beliefs relating to the work at hand can raise issues and explore alternatives without fear of judgment or bias. A neutral location is ideal and helps create “equal footing” for all.

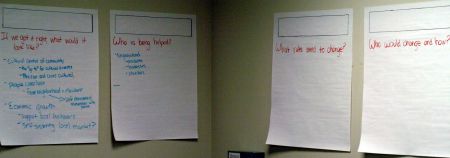

A blank flip chart sheet for each of the eight steps outlined below should be taped to the wall at the front of the room, visible to all participants. The flip charts are set up to include an empty box at the top (see figure 1), with one or two questions that are to be addressed written below the box. The empty box is filled in at the very end of the process, when the technical terms are shared with the audience. The eight steps are placed on the wall in the traditional order of a logic model found in online visual guide (http://prezi.com/nq6lm8enl87f/tearless-logic-models/) but the audience will address them in a different order described below. Having a detailed agenda handy is also a prudent idea. One additional flip chart (#9) should be placed on another wall in the room with the heading “Parking Lot.” This will be useful for capturing an idea or discussion point that is not relevant to the Tearless Logic Model discussion. Using the parking lot is a simple way to redirect the group to the task at hand.

Finally, because of the realities of group dynamics, it is useful for facilitators to go into a meeting like this with a clear picture of the order of events and the division of responsibility. A detailed agenda for the facilitators helps keep the process on track and ensures that all steps are completed. Detailed agendas for facilitators can take many forms. Below is a simple template with space to include information that we have found useful in such meetings in the past. (See PDF copy for the sample template.)

It is a good idea to have the purpose of the meeting explicitly stated for reference throughout the process. When creating the agenda, think about what you will need to take with you and how you will set up the room. The task of staying productive and on-topic is made easier by a detailed play-by-play including a time column, a task description column, and a special notes column. The more consideration given to the flow of the meeting before it takes place, the less likely it is that the process will be unexpectedly hindered.

Facilitation of the Tearless Logic Model

Facilitators should be geared towards leading an appreciative inquiry session about where the group or organization sees its future. To reduce the intimidation factor, we recommend leaving the words “logic model” off of the session title and invitation to participants as well as out of the facilitation process. Two facilitators are ideal, so that while the conversation is happening, one can record answers on the flipcharts while the other continues to engage the group. Once you’ve familiarized yourself with the steps, feel free to adapt them to your own group.

It may be wise to conduct an “ice breaker” activity at the beginning of the session in order to relax and engage participants. One possible icebreaker activity is “two truths and a lie,” in which the facilitators say two truths and a lie about themselves and the group members guess which of the statements is the lie. Another easy icebreaker activity is a pop-up exercise, in which group facilitators ask a question of the group and those who agree with the question stand up out of their seats. The purpose of these icebreakers is to get everyone talking, get to know each other, encourage participation, and lighten the mood.

Step 1: Anticipated Impacts or “End in Mind”

Recognizing the importance of starting with the end in mind starts with a set of questions related to anticipated impacts. Rather than using traditional logic model language, pose one of the following questions:

Record the discussion on a flip chart labeled “If we got it right, what would it look like?”

Step 2: Target Population or “Those We Serve”

After establishing the end in mind, vision, or preferred future of the program or organization, the next step is to address the target population or persons served. Ask these questions:

Record the discussion on a flip chart labeled “Who is being helped?”

Step 3: Long Term Outcomes or “Policy Changes” or “Changing the Rules and Nature of the Game”

After identifying persons served, refer back to the end in mind or vision for the program and ask about the types of system change important to reach that vision. Use the following questions to identify changes:

Record the discussion on a flip chart labeled “What rules need to change?”

Step 4: Intermediate Outcomes or “Behavioral Changes”

After identifying the necessary changes in policy, practices, and programs, the next step is to narrow the focus to those behaviors and actions that will lead to these changes. The following questions will help you achieve that goal:

Record the discussion on a flip chart labeled “Who would change and how?”

Step 5: Short Term Outcomes or “What Needs to Change Right Now”

After identifying behavioral changes, the next step is to focus on immediate/initial changes. Pose the following questions to identify initial changes in attitudes and beliefs:

Record the discussion on a flip chart labeled “What are the first changes you expect?”

Step 6: Activities

After identifying initial changes, it is important to identify the essential activities that will lead to this change. Ask the following questions:

Record the discussion on a flip chart labeled “What must be done?”

Step 7: Outputs or “What Can Be Counted”

Most program activities have corresponding outputs or products. After identifying the activities, discuss what the activities will produce. Pose the following questions:

Record the discussion on a flip chart labeled “What can be measured?”

Step 8: Inputs or “Resources” or “What do we need to make it happen?”

After identifying the activities and outputs, it is important to determine what resources are needed to fund and staff the activities. The following questions will determine the resources the organization already has and what they need:

Record the discussion on a flip chart labeled “What do we need?”

Step 9: Revealing the Logic Model

After completing the discussion on resources, briefly review each of the flip charts with the group. Restate the purpose of the meeting. Once this purpose is restated, add labels to each of the flip charts to reflect traditional logic model language. You can then point out that the group has unknowingly created a logic model—without tears!

Step 10: Creation of the Logic Model

Once you have identified the major components, it is important to transfer what you have identified into a more structured logic model. This can be accomplished by an individual or by a small group. The group may decide that it is desirable to have an experienced individual create a final product based on the group’s input. With the option of having one person create the logic model, group input is received during the session and is synthesized by one person into the logic model. A small group of individuals can also be used to create the logic model in real time. The small group should include the individual with experience in creating a logic model in addition to several other members of the larger group. This smaller group can analyze what has been decided and bring the content together in a coherent way by aligning the content with the appropriate column using traditional logic model language.

By approaching the logic model in this step-by-step way, individuals involved are less intimidated by the process and are able to focus on accurately answering questions about their program, project, or initiative. This process is also time-efficient. Depending on the size of the group and the personalities present, this process can be facilitated in as little as two hours, less than many other traditional logic models. The Tearless Logic Model is just one example of how organizations can be encouraged to do outcome-based planning and logic model development. Ideally this process and others like it will result in organizations having positive and successful experiences and will reduce their fear upon hearing the words “outcome-based planning” and “logic model.”

Ashlee D. Lien, Justin P. Greenleaf, Michael K. Lemke, Sharon M. Hakim, Nathan P. Swink, Rosemary Wright, and Greg Meissen

Ashlee D. Lien, Justin P. Greenleaf, Michael K. Lemke, Sharon M. Hakim, Nathan P. Swink, Rosemary Wright, and Greg Meissen

Community Psychology Practice and Research Collaborative, and Community Psychology Doctoral Program, Wichita State University, Wichita KS, USA

![]() Download the PDF version to access the complete article.

Download the PDF version to access the complete article.

Keywords: logic models, community psychology practice, gjcpp