Community psychology (CP) attends to the challenges facing communities in our efforts to bring about justice and well-being. We are explicitly concerned with understanding the origins of oppression within various contexts, using diverse approaches. It is therefore necessary to reflect on our conceptions of practice where our diverse roles in the community facilitate collaborations within and across complex cultural contexts (Jimenez, Sanchez, McMahon & Viola, 2016). This article introduces a continuum of CP praxis emphasizing the need for an increasing awareness of the history of oppression, the need for epistemic justice, and ways in which power is built into the sciences from which our field has grown. We hope that such a continuum will help us better frame our practice, as it provides a framework for holding multiple worldviews toward a more ethical, relational praxis.

Download the PDF version to access the complete article, including figures and tables.

“…philosophy will be able to increase the amount of justice, beauty, and truth in this world only when its practitioners begin to exhibit genuine pluralism in their work.” (Mungwini, 2019)

Community psychology (CP) attends to the challenges facing communities in our efforts to bring about justice and well-being. We are explicitly concerned with understanding the origins of oppression within various contexts, using diverse approaches. It is therefore necessary to reflect on our conceptions of practice where our diverse roles in the community facilitate collaborations within and across complex cultural contexts (Jimenez, Sanchez, McMahon & Viola, 2016). This article introduces a continuum of CP praxis emphasizing the need for an increasing awareness of the history of oppression, the need for epistemic justice, and ways in which power is built into the sciences from which our field has grown. We hope that such a continuum will help us better frame our practice, as it provides a framework for holding multiple worldviews toward a more ethical, relational praxis.

Setting Our Intentions and Positionality

The purpose of this paper is to offer readers a re-conceptualized definition of CP practice. Recognizing the need to address the way coloniality is embedded with CP we first mention how our own positionality has influenced our approach. We chose to write the current paper in first-person narrative to ensure we keep clear the contextualized nature of our conceptualization. We intend for this paper to support epistemic justice. In other words, getting across the ways we value forms of knowing beyond the more dominant cultural values system embedded within the North American/Western context.

We are CP practitioners living in the Chicagoland area of the United States (U.S.); one of the most diverse urban landscapes in the country. Tiffeny Jimenez, Judah Viola, and Brad Olson are tenured professors at National Louis University. Ericka Mingo is a graduate of the NLU doctoral program and full time faculty member. Christopher Balthazar is a current PhD student in the NLU doctoral program. We have each spent years working as employees or consultants to non-profits and government-funded projects or agencies (e.g., Chicago Public Schools, State Councils, Museums, Community Based Organizations, National Housing Nonprofits, Disability Advocacy Organizations, Foundations, and Federally Funded Grants). On a more personal level, one author identifies as female, mestizaje, and queer, as part of a broader earth-cycle-connected sense of self. Two authors identify as Black, while one is female and the other is male and identifies as queer. There are also two white-bodied, cis-gendered males without impairments. Through these varied perspectives, and recent months of discussions with CPs around the U.S.[2] we offer an additional perspective on CP practice, including a revised definition and model of a continuum of CP praxis.

Cycles of Praxis

A reexamination of CP practice ought to consider the ways in which community psychologists engage in an ongoing process of collective-action-inquiry-reflexivity (i.e. praxis). Such a praxis should possess clear points of reference to power, politics, and ethics aligned with liberation psychologies (Martin-Baró, 1994; Montero, Sonn, & Burton, 2017). This article reexamines the ways in which we enact CP practice; without asserting any specific tasks or roles for a practitioner. Nevertheless, these recommendations are broadly applicable to all community psychologists, regardless of their role/positions across various organizational contexts (e.g., academia, nonprofit, healthcare, government, consulting, etc.); as well as across related disciplines. Focusing on practice as cycles of praxis (see Olson & Jason, 2015) means further examining who we are, where we are, and how we decide to engage with communities; an examination of theory as it experiences situated within context; i.e., liberating ways of knowing (Freire, 1970; hooks, 1991; Martin-Baró, 1994; McKittrick, 2015; Pitts, Ortega, & Medina, 2020).

More specifically, we examine aspects of praxis in light of our intentions, our purpose, our positionality, and the power embedded in settings and relationships. From this standpoint, we offer a temporally-oriented, community-integrated model of cyclical praxis--one that involves ongoing co-learning, with inquiry, with equal collaboration with partners, with theory, and through deliberative scholarship. Community psychologists work with others, deliberating with stakeholders, making new connections, and reflecting on what we learn in that process through cycles of writing/reflection, discussion, critique, creation, inquiry, and action.

Our cycles of praxis are grounded in place, in relationship to culture, and in an analysis of power. Most of all our praxis is rooted in the sincere efforts of community psychologists to connect with others. We work to understand the politics embedded within the history of geographies and institutions. We remain in dialogue within deep tensions. We mutually reflect on the philosophies of science and action we choose. We believe that through this ongoing collective process we can (un)learn the myth of neutral, bystander ideologies. We develop theory that is reflective of lived realities, and attempt to bring new emancipatory realities into existence (Gergen & Zielke, 2006).

Our Emergent Definition

In his Community Practice Model for CP, Julian (2006) opened a dialogue around an understanding of community psychology practice and the community psychology practitioner. First, Julian advanced thinking about the community practitioner by describing someone with a recognized (often but not necessarily) paid role in the community, engaging in long-term improvement interventions that involved continuous evaluation, planning and implementation. Second, he asserted four sets of skills for the successful community psychology practitioner: (1) community mobilization; (2) planning and decision-making; (3) implementation; and (4) evaluation. As the foundation of his definition, these skills form the basis for community dialogue and data informed decision-making; with the collective goal of addressing specific community challenges.

Data-informed practice requires input from stakeholders. Our definition goes beyond traditional connotations of data, requiring historical and demographic data, analysis, observation, conversation, and meaning making. This interpretation of data more fully lives up to Julian’s (2006) definition of community practice as: the collection of communal understandings, aimed at community improvement and intervention, through the aid of a community psychology practitioner, implementing four core skills, community mobilization, planning, decision-making, and implementation.

A New Perspective

Revision of the existing definition for CP practice begins by questioning assumptions about where CP is practiced. Overwhelmingly, CP has been practiced in communities conceived as “disadvantaged groups”, existing under oppression, occupation, or some other form of strife—often communities of color. Too often, this work reflects programs engaged in first-order rather than second-order change. While community psychologists work collaboratively with community members we must also engage in critical and activist practice directed at power structures—we work “with” our partners to dismantle structural violence.

With this paper we hope to challenge the field to think of practicing engaged inquiry in places we have not spent enough time in the past (e.g., in the face of agents and structures of oppression). Such places are often unnoticed, yet are fundamental when attending to those who hold power over people and other living beings. These are the places, the structures, the policies, and narratives that uphold and protect ideologies and ways of the oppressor.

Justice, in any community, is an increasingly articulated, desired outcome of community action. All too often, when we engage in justice work, it is an add-on to our inquiry and programming as opposed to an intrinsic part of the practice. Even the actions in the field of social justice policy change can be more first than second order. There is more we can do to shift structural and cultural landscapes (Olson, Viola, & Fromm-Reed, 2015; Olson, O’Brien, & Mingo, 2019). To this end we hold that social justice should be embedded in any definition of practice

Communities can be perceived as broad, including any group of people with shared goals and a shared fate--meaning that it applies to any social groups that believe in holistic and integrated ways of being, tied to historical and geographic, land-based or also more electronically dispersed spaces. Respecting these spaces requires the community psychologist to de-center our own professional trajectories, to strive toward better alignment with those doing work often very different from our own.

Beyond new perspectives around what is practice and who is the practitioner, community practice should grapple with balancing collaborative efforts with efforts critical of power structures. This will allow us to better mobilize our practice in terms of more equal collaborative interventions toward altering harmful, unjust, narratives, processes, and policies.

This brings us to a renewed definition of CP practice:

Community Psychology (CP) praxis is a collective action, capacity building process in which a community psychologist engages a community area, organization, or social group, in an effort to collectively remove barriers to lateral interdependence, autonomy, and self-determination. This work takes place both within groups suffering from oppressive barriers to wellness and those responsible for setting up or maintaining those barriers. Community mobilization, planning, decision-making, and implementation are developed through the collection of communally constructed understandings and shared praxis. This work requires the community psychologist deeply (encouraging outside critique) aimed at developing their most optimal role, based on clarity of intent, purpose, positionality, power, and relationality.

This definition of CP practice/praxis can be enacted by all community psychologists, regardless of whether one is situated in a university, government, human services, NGOs, or the private sector. Our definition is an attempt to provide a flexible base for holding multiple worldviews in order to move towards a more ethical, relational praxis. It attends to the politics and philosophies of action/science, which includes resurgent calls for justice, evident within post-colonial and decolonial scholarship.

Intentional Reflexivity on Global Citizenship

We need to be more reflexive as global citizens, intentionally exploring harmful dominant systems. Given that the undercurrent of our collective unconscious and associated language guides how we think, act, and relate to others, reflexivity involves making clearer the assumptions embedded within various settings that shape our character, our emotional reactions, and subsequent behaviors. There is much observable harm prevalent today to which we have been desensitized. We are learning to see more clearly how our praxes in service of the dominant culture contributes to harm.

We understand that the work we do within the local Chicagoland area is interconnected with a larger sense of critical global citizenship and interdependent with larger systems of oppression (Morales & de Almeida Freire, 2017). Through an onto-epistemology of interdependence, we believe the fate of our communities, and those of our students, are tied to the reality of those who occupy other geographic spaces on the planet. This universalist approach makes it of critical importance that we create opportunities to educate ourselves, and others, about this larger context, and how we are shaped by global events/dynamics, (Escobar, 2020). It is with this foundation in mind that we also work to build a global sense of community that emphasizes the world as an interconnected, interdependent, whole living organism, and that can allow for global collective action (See Marsella,1998 for similar points and implications for education and training for a Global-Community Psychology).

We believe it is important to acknowledge how various social groups and certain geographies have intentionally been oppressed for the benefit of others (de Sousa Santos, 2007; Escobar, 2020; de Sousa Santos, & Meneses, 2020; Mbembe, 2019). For example, we acknowledge that globally, people of northern regions have enacted structural and cultural dominance over those of the Global South (i.e., African, Latin American, South Asian), which has led to inhumane living conditions for many. While we are careful not to emphasize the binary inherent in this understanding (North vs South), we do acknowledge that people more commonly of the northern geographical locations have enacted violent acts against those of the Global South for centuries. This complexity acknowledges that a Euro-Western-imperial ideological lens involving militarization, theft, racism, and abuse have together depleted a variety of natural and cultural resources from those community areas (Caouette & Kapoor, 2013; Grosfoguel, 2020; Mungwini, 2019; Teo, 2010). (See activists working to raise consciousness of this, for example, https://youtu.be/UAYhRUj9VOI).

The ongoing reality of the history of colonial forces impacting everyone on the planet, even though we are living in “post-colonial” times, is currently termed coloniality (Maldonado-Torres, 2007; Quijano, 2000). We believe acknowledging this history is critically important because the mindset embedded within this way of being is still present in and across almost all settings of the world we live in today (McKittrick, 2015; Mignolo & Walsh, 2018). It is from this critical perspective that we can more clearly see the harms happening within our own local settings as they tie into a larger framework and systems of oppression happening across madre tierra (Mother Earth) (e.g., capitalism, neoliberalism, racism, extractivism, etc.). An expanded context clarifies the importance of acknowledging multiple ecologies of knowledge (de Sousa Santos, 2007); the importance of relational ethics (Hopner & Liu, 2021; Norsworthy, 2017; Tucker, 2018); and why we believe in working together (co-laboring) to co-construct pluriversality – a world of many worlds (Escobar, 2017; Escobar, 2020; Rojas, 2016). It is with this global-community context in mind that we introduce the continuum of CP praxis.

Placing the Continuum of CP Praxis in Historical Context

A brief overview of the social sciences, and field of CP, shows alignment in shifts that have occurred over time. Much of the social sciences developed in ways that sought to replicate understandings about the reality of society through a positivist or post-positivist lens, a way of inquiry using methods seeking generalizations about universal human traits, behaviors, and motivations.. This kind of work seeks generalizations about universal human traits, and stems from scientific criteria developed from the “hard sciences” perspective in which we assume there is a single, external reality or truth that can be measured, understood, predicted, and controlled. Human and social systems however, are different, and have, therefore required a shift in scientific paradigms and methodologies.

Differing organizational settings are also tied to these earlier scientific paradigms. Institutions such as medical research facilities and clinical research settings engage in projects where basic research criteria or clinical trials are necessary, and linked to larger policies related to human “subjects,” “safety,” and “rigor.” These kinds of institutions are also concerned with disseminating evidence-based practices through interventions designed to reach diverse populations (e.g., public health), often utilizing community health workers to connect with populations deemed “hard to reach.” One critique of the translational sciences paradigm is that it has over-enforced or imposed Western medicine and therapeutic approaches on people who believe in other ways of healing and well-being (Gone, 2007). This paradigm has created whole lines of inquiry that emphasize human difference, deepening grooves of stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination (e.g., racism, sexism, ableism) (Ruti, 2015; Tucker, 1996; Yakushko, 2019a; Yakushko, In Press).

In a first wave of professional growth in the U.S. (~1965-1991), CP grew out of a desire to shift the focus of practice to understanding the environmental forces that create oppressive situations (Kloos et al. 2012). The development of CP was based on the professionalization of the Psychologist, as a laboratory-oriented research expert, who learned how to take into consideration environmental factors that influence the human experience. However, the community-level, action-oriented aspects associated with changing conditions linked to structural problems did not receive as much attention in the U.S. as it did in other areas around the globe (Reich, Riemer, Prilleltensky, & Montero; 2007; Reich, Bishop, Carolissen, Dzidic, Portillo, Sasao, & Stark; 2017). Within the U.S., this did not occur until the rise of CP Practitioners who were concerned with the outcomes of interventions more than the purity of the science that went into their design (See: https://www.scra27.org/publications/tcp/tcp-past-issues/tcpfall2015/community-practitioner/). Undoubtedly, this shift led to the perception that there are two distinct groups of community psychologists distinguished by the professional standards associated with the organizational cultures in which they work and incentives embedded within those contexts – i.e., either academia or everywhere else.

In a second wave of professionalization (~1992-2012), there was an increase in the awareness of CP practice that emphasized the implementation of CP principles in community, nonprofit, government, and health settings. This second wave was also characterized by the rise of qualitative methods and the constructivist paradigm (Denzin, 2009), a shift acknowledging unique realities of individuals and questioning generalizable claims about the experience of people in context. Generating new forms of knowledge based on CP principles applied in practice began to counter the perceived hegemony and adulation of academic-based researchers in the field. The practice of non-academic CP practitioners became increasingly known through publications, SCRA awards, and CP practice competencies being implemented in graduate programs (Sarkisian, Saleem, Simpkin, Weidenbacher, Bartko, & Taylor, 2012). Overall, there has been quite a bit of growth and development in the practice of CP, and one of the most important aspects associated with increased acknowledgement of CP practice was the awareness of the disconnect between the values embedded within a stance of research or practice. More importantly, within this awareness, while not entirely explicit, was the realization of a hierarchy; where research designed by experts within academic institutions was more valuable than the perspectives, concerns, questions, and ways of being experienced among everyday community members. Today, we attempt to unseat this rift within a renewed conceptualization.

Introducing a Continuum of CP Praxis

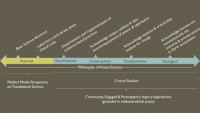

Historically, CP within the U.S. has been conceptualized as being comprised of either those who engage in CP research or CP practice (Bennet, Anderson, Cooper, Hassol, Klein, & Rosenblum, 1966; McMahon & Wolfe, 2016; McMahon, Jimenez, Bond, Wolfe, & Ratcliffe, 2015). For example, past data for understanding the CP practice competencies (Dalton & Wolfe, 2012) has asked community psychologists who filled out a survey to place themselves within one of two groupings, as being community-based or university-based. This distinction between the roles of a community psychologist employed by a university versus a community psychologist employed by any other type of agency or organization may have been helpful for developing CP as a legitimate field of study within the broader context of professional Psychology. In our current historical context, however, we suggest that considering the roles of a community psychologist consistent with multiple points across a continuum could help to capture a more nuanced understanding of the unique, cross-fertilizing, boundary spanning contributions of all community psychologists. We believe this new conceptualization of CP practice as a continuum and temporal cycle allows for more clarity regarding the assets embedded within the varied contexts of our work. It emphasizes the assets of each possible employment setting, and across disciplines, which we hope can increase collaboration across the field for the purpose of a larger sense of transdisciplinary, community well-being and efficacy.

Figure 1: A Continuum of Community Psychology Praxis (Download the PDF version to access the complete article, including figures and tables)

Examining more closely the philosophy of action/science in which we community psychologists engage in any setting requires us to be explicit about our orientation to the world when we participate in community-engaged and participatory inquiry approaches, including assumptions about ontology (nature of reality), epistemology (nature of knowing reality), axiology (what has value), ideology (role of values and politics), and methodology (tools used to obtain knowledge). Clarifying this underlying paradigm within our projects requires us to be clear about the kinds of questions we consider legitimate lines of inquiry, what counts as knowledge, which forms of knowledge are privileged within any particular project, and the intentions behind projects such as how data will be used and for whose purpose. In terms of relational ethics, this deeper examination of our assumptions about the world encourages an examination of power – who has it, and how power will be wielded within a specific context.

Everyone benefits when we are able to hold a deeper understanding of how the settings in which we work (“where we work”) shapes the philosophy of action/science underlying our approaches to working hand-in-hand with communities (“how we work”). The CP praxis continuum (see Fig. 1, download the PDF version to access the complete article, including figures and tables) illustrates a philosophy of action more than a philosophy of science, indicating that CP praxis is action with science integrated in the unique ways we enact our roles in any setting. In other words, our paradigms associated with science are inextricably linked to our relationships with communities through praxes associated with community-engaged and participatory inquiry approaches (Israel, Schulz, Parker, & Becker, 1998; Olson & Jason, 2015) explicitly grounded in relational ethical praxis.

How we perceive data, and how we use data in various spaces are embedded within both the unique worldviews of organizational settings we occupy, as well as the paradigms we personally lean into; either due to paid contracts, structural conditions and discourses surrounding a particular issue, or our own preferred philosophies of action/science. From this perspective, all projects using any type of information as “data” are enacting some philosophy of action/science and are included in this new conceptualization of CP praxis. This includes all types of projects that are empirically grounded, including, for example, different types of evaluation, use of qualitative data as part of a participatory or facilitated process, interventions using data to understand the value of certain identified variables, or using visual data metrics to raise consciousness or capacity to work more collectively.

This continuum allows us to hold multiple types of data and methods as part of a philosophy of action/science; therefore, the use of the term “data” will be used throughout this paper to refer to all forms of information being used to inform social action. Maintaining a deeper understanding of our paradigms within settings, increasing awareness of our relationship to the politics within settings, and interrogating how these factors inform all actions are essential elements of our CP praxis. Analyzing our philosophy of action/science and positionality within settings related to any number of problematizing projects within and between settings (i.e., alternative spaces) is what we refer to as “the work.”

Unpacking the Continuum

There are two main components incorporated into this concept of a CP praxis continuum: (1) the translational sciences continuum used from a medical model perspective (Drolet & Lorenzi, 2011); and (2) a framework of major research paradigms for considering the worldview or paradigms we carry through our philosophy of action (Riemer, Reich, Evans, Nelson, & Prilleltensky, 2020). When considering the unique needs required by different groups to experience well-being and thrive, we view the integration of these two frameworks as complementary and allowing for raised consciousness regarding the role of a community psychologist. The continuum of CP praxis also aligns with aspects of an article by Tebes, Thai, and Matlin (2014) regarding needed approaches to science for the 21st century, so the connection to this framework is discussed here as well.

While the past conceptualization of CP practice has assumed that the practitioner is one who implements theory and knowledge from science into community settings (Julian, 2006), it is important to acknowledge that supporting and promoting science for the unique conceptions of well-being held by a variety of social groups also occurs through other means. Based on our revised definition, this involves privileging the perspectives of historically marginalized groups to ensure they are taken seriously, generating knowledge blended with relational and co-laboring processes for developing new understanding about what qualifies as conditions for well-being, or merely working to clear barriers to well-being in cases where assumptions have been made about what people need (i.e., concepts of health). In this sense, the CP praxis continuum inevitably holds a critical stance in that we acknowledge, and need to act against, the long history of oppression of certain groups that has led to health disparities. This raises the necessity of questioning traditional Western professional expertise based on certain dominant conceptions of science (Gone, 2007). This acknowledgement on a global level compels us to seek deeper understanding of epistemological diversity and plurality, and question the ways cultural hegemony has occurred in the name of universality (Reiter, 2018).

On the Left: Translational Sciences

Moving from left to right (See Fig. 1), projects that occur within the left end of the continuum (see the gold coloring) include those grounded in the assumptions of the biomedical research, translation continuum. They involve the translation of laboratory-based or clinical treatments to humans. These projects use positivist or post-positivist research methods and testing via practice-based research for public health purposes. This type of work includes drug or therapeutic dosage testing and assumes that professional knowledge and methodologies (e.g., clinical trials, experimental conditions) are necessary before such interventions are deemed safe enough for human application/use. There are a number of behaviorally focused approaches that have applied community psychology values in the development of interventions for issues such as drug addiction, bullying, recycling, and illegal sales of cigarettes to minors (See: https://press.rebus.community/introductiontocommunitypsychology/chapter/behavioral-approaches-in-community-settings/). In terms of public health benefits specifically, the study of translational science has become an important research priority to learn better how knowledge progresses to health gains given that significant health benefits are often lost in translation (Drolet & Lorenzi, 2011).

There is a range of CP praxis that attends to a variety of possible projects within the blue side of the continuum. For example, we have been involved in implementation of prevention interventions for public health needs where we apply evidence-based knowledge and use quantitative survey data to test effectiveness (post-positivist) for a program within a particular setting. This could be a cancer-screening program, or an evaluation of an intervention designed to support caregivers of people with Alzheimer’s. The efforts may utilize quantitative and qualitative data for both formative and summative assessment. Other projects might involve collecting data to document or acknowledge differences in experiences, examining unique lived realities that assist in uncovering harmful variables. We might interview people experiencing homelessness in Chicago to learn more about how city dynamics influence a person’s ability to maintain housing, thus identifying levers for structural change. While one might interpret this section as “research,” we see this dialogue as fundamental to the action-based praxis cycle. The decisions made and solutions decided upon in any data-to-action event lie in the shared decisions co-created by all stakeholders, not simply the “analytic” or theoretical contributions of the community psychologist(s).

Acknowledging that all project data is tied to larger transdisciplinary, ongoing complex systems change and discourse, it is important to note that projects might start out grounded within one paradigm, then merge into similar paradigms as data links to other spaces, sectors, and organizations within the system. A constructivist approach may require a qualitative data orientation in a relational conceptualization of CP praxis, and may lead into another project using different types of data and to different stakeholders.

In many cases, it can be a challenge to identify where one project starts and another begins. This is the nature of conceptualizing CP practice as ongoing cycles of praxis (Olson & Jason, 2015), and it is important for following the flow of knowledge movement as we seek knowledge generated to shape existing structures. Therefore, many projects often become mixed-methods approaches in the name of pragmatism to ensure the usefulness of data depending on the diverse groups and organizations involved, as well as the supports needed to link to next steps in working to disrupt the flow of the system.

On the Right: Critical and Transformational

The far right side of the continuum represents how we community psychologists can be involved in projects/processes that take a critical stance to dominant historical, structural, and cultural system dynamics. We may collect data in this instance with the intention of shifting discourse, power dynamics, or raising consciousness about the nature of resources or how to maneuver resource distribution (i.e., more transformative forms of change). Such an effort might include projects where we work to document how dominant systems function as systems of oppression that have created barriers to well-being for indigenous communities in real world settings while simultaneously validating indigenous knowledge systems (Indigenous). The first author is, for instance, supporting the work of the Native American Center’s goals to ensure proper education about Native Americans in the Chicago Public School system and to collaborate with artist/activists to bring awareness around the land that was unapologetically taken over by the city (For information on a current related project called “Whose Lakefront,” see https://www.jeeyeunlee.com/).

Transparadigm Approach: Critical Realism

The transparadigm approach of critical realism (Bhaskar, 2002), a modern school in philosophy of science—from post-positivist to post-modernist (Lauzier-Jobin, Brunson, & Olson, in press)—spans the CP practice continuum. Critical realism allows for understanding whole[3] community systems, unpacking the elements of harmful and violent systems of knowing and being that enable oppression of certain social groups within and across geographies. Critical realism is a way of seeing the world of CP praxis as a philosophy of inquiry that allows for integration of ontological realism and constructivism or interpretivism. This view recognizes that there are things in the world that are real, there are events that occur, and there are empirical observations we can make about these events. The critical realist paradigm allows for holding both knowledge of shared reality (e.g., structural system dynamics, politics, organizations, etc.) as well as diverse epistemological standpoints. “Even if one is a realist at the ontological level, one could also be an epistemological interpretivist…our knowledge of the real world is inevitably interpretive and provisional rather than straightforwardly representational” (Frazer & Lacey, 1993; p. 182).

This orientation, that there is a real world that exists independent of our perceptions, theories, and constructions, means that there are established truths about a shared reality (some things about systems are identifiable and generalizable). At the same time, we also view and seek to understand socially constructed, local realities (social groups hold unique realities – some things are not generalizable). Therefore, we view the critical realist paradigm as inherently critical in orientation given modes of inquiry continuously encourage critical analysis incorporating multiple types of data and divergent perspectives, including perspectives on the nature of reality (ontology). As Gorski (2013) states, “A genuinely scientific realism is necessarily a critical one, which continually reflects on and revises its own categories and instruments. Its ontology is provisional and fallible” (p. 2/659). Furthermore, when applying this approach toward the social world we believe that a focus on power dynamics as part of the critique is essential to understanding the past, present, and future of settings and groups, as well as person-environment fit.

A critical realist paradigm of inquiry encourages transdisciplinarity in order to understand various layers of truth and reality. It also encourages a connection between knowledge and action. Generating, connecting, and moving the flow of knowledge is done to help guide the way we act to promote well-being in the world. The comprehensive nature of the critical realist paradigm encourages us to explore multiple perceived truths and multidimensional ways of understanding truth and lived realities, including how contexts, needs, and narratives shift over time.

When considering the relational aspects of this new definition of CP practice, and working transdisciplinarily, we find points of alignment with an article by Tebes, et. al. (2014) on 21st century science that refers to the work as a relational process. They suggest that CP embraces a more collective-action “team science” to bridge various transdisciplinary knowledges and for science to better link research and community practice. Unfortunately, power inherent in academic settings can place community-driven data at a disadvantage, particularly in what the various institutions regulate and authorize as “valid” perspectives shaping system policy/practice. Dominant policy institutions are those supported by government efforts that favor post-positivist forms of professional knowledge, hence controlling what data and lines of inquiry can shape systems of care and the distribution or preservation of resources (e.g., natural ecologies). The continuum of CP praxis helps us appreciate multiple emergent ecologies of knowledge beyond the dictates of scientific rigor and acknowledges the history of intentional marginalization of certain voices and ways of knowing/communicating (i.e., sociolinguistic justice). Instead, we engage in connecting with how a broader group of people view the world, all of which are legitimate forms of data, and it comes down to us more intentionally, calling out power dynamics and prioritizing relational ethics.

The continuum of CP praxis addresses these limitations by uplifting the importance of examining an embodied and relational experience of acting alongside, adding to, and contesting the dominant discourse on how to perceive and act on social problems (e.g., mental health challenges, health disparities). Through use of this continuum of CP praxis, we acknowledge that relationships are dynamic and data includes more than what is intentionally collected through the limits of a scientific lens and agenda. We believe in more fully embracing what it means to be in relationship with, and within a thicker understanding of history, time, and diaspora. From this stance, we are moved and move others, through empathy and a deeper connection to understanding our shared pain and interdependence (Alzaldúa, 2015).

In summary, the continuum of CP praxis, situated within the localized political, cultural, and situational dynamics of a community system, indicates that knowledge is generated from various interpretive frameworks/paradigms, not only from positivist or from even post-positivist research paradigms, as was once assumed. The knowledge generated is shared, contemplated, debated, taught, and critiqued from multiple stakeholder perspectives. Through this ongoing dialogical process, through an increased consciousness and capacity, there is brought a greater potential for cultural and structural change. This is why the arrows within the model flow horizontally from left to right, indicating that all knowledges gained from the various methodologies are equally valid within the work of CP praxis.

We believe it is our job to insist on this values-forward framework (axiology). From a CP praxis standpoint, merely acknowledging that various types of knowledge are valid brings new perspectives into general or scholarly debates, however, we believe this does not go far enough and could be working against directing resources to tangible and needed change. Clarifying how epistemic injustice manifests in our daily lives, within our institutional and organizational settings, and therefore everyday situations, requires further unpacking and clarifying relational ethics in daily praxis. Given that CP praxis happens within a historical, cultural, and community context, we believe it is important to first consider how these dominant cultural dynamics have contributed to epistemic, social, and cultural injustice, and then reverse-engineer the strategies.

Applying the CP Praxis Continuum to Understanding Institutions and Organizations

Understanding the ongoing dominant cultural dynamics of our complex community systems involves understanding institutional and organizational settings. We consider how the worldviews and practices of each are distinct from one another within a larger city setting, and how these dynamics work together for larger purposes (Jimenez, 2012). Each organization embedded within a geographically specific setting plays a role in a larger system of established policies and practices intended to serve the needs of communities. These policies and practices are embedded within particular worldviews that can be located along the continuum of CP praxis.

Just as any individual community psychologist effort can fall somewhere along the continuum of CP praxis, so too can those efforts of whole organizations, sectors, broadening from state to global levels of governmental entities. Differing organizations are shaped by disciplinary scholarship and adhere to certain philosophies of action/science. They make whole sets of assumptions about the development, use, and allocation of resources based on particular ways humans are believed to relate to the natural environment (ontology) and certain ways of knowing (epistemology). In fact, this is how universities play a role in shaping how our complex community systems perpetuate injustice. The structural and colonizing function of academia highlights the problem with the power afforded to “science.” This is problematic for CP work in general, given that the most valued work has been traditionally sourced within these elitist entities; and based within Cartesian philosophical assumptions about human reality and knowledge. The assumptions embedded in the format of scientific writing, the role of a university faculty member as an expert in disciplinary content areas, and the incredible amounts of resources funneled into supporting hierarchical relationships from universities to their surrounding communities—these embedded factors all play a role in sustaining oppressive ways of knowing and being. Therefore, if we hope to change which perspectives are taken seriously within the configuration of our community systems, while truly uplifting the needs and perspectives of those social/natural communities we care about, we must address those forms of structural violence that have continued to oppress. It is the role of community psychologists to uncover the seemingly invisible, underlying ideologies inherent within these systems (Jimenez & Barhouche, 2021). Part of CP praxis is engaging in critical reflexivity on the community systems in which we are embedded and promoting collaborative critical thinking with our partners in our daily work to increase awareness of harm (Evans, 2014). This level of problemitization is needed so we can break down how settings built within a colonizing standpoint perpetuate destruction of the human spirit through their very existence (Freire, 1970).

One example to explore here is the kinds of activity associated with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS). The DHHS is by nature a federal department comprised of multiple agencies that send federal funds and guide state dollars to financially support organizations that provide resources such as food, shelter, and counseling supports to alleviate the stresses that manifest within a hierarchical capitalist system (INCITE!, 2007; Kivel, 2009; Renz, 2016). The governmental agencies hold the power, distributing resources according to certain assumptions about which organizations deserve to be funded and valuing certain ways their services must be evaluated as effective. Health services are tied to epistemologies emphasizing the left end of the continuum of CP praxis (positivist/post-positivist), indicating that professional expertise and evidence-based practices are the desired criteria for determining what is funded and therefore what is available to the public.

In this case, assumptions embedded within positivist and post-positivist philosophies of science determine how we attend to the health needs of a variety of communities, some of whose members do not believe in the forms of knowledge generated by the science that has been prioritized (e.g., indigenous ways of knowing). Moreover, it goes even deeper than this when considering assumptions embedded within dominating structures of city and state. In this kind of scenario, the intersection of assumptions about science in this organization (DHHS) about health, and humans, mixed with city policies, and federal control mechanisms (i.e., policy) regarding land and resources at local levels (i.e., privatization), all get in the way of allowing people the self-determination needed to experience life/health in ways harmonious with their spiritual, social, and cultural worldviews (Fadiman, 1997). It is through this epistemological control that institutions perpetuate oppression.

Locally, we try to better identify how our work spans the continuum and supports greater collaboration with those of us around the Chicagoland area, and is invested in creating a better future. All data is and can be useful for changing community culture and system structures, yet there also needs to be explicit awareness and articulation about how different epistemological standpoints carry more or less weight when bringing data into dialogue. Grappling with application of the continuum helps us and our students better engage with our communities in an inclusive way. This continuum exists in a way that includes all community psychologists and their work to be enacting some form of CP praxis. While it can be argued that many, if not all, community psychologists are engaged in, or focused on achieving some level of social/systems/transformative change, the process and manifestation of this work looks different with different approaches, different settings, and spaces.[4] Community psychologists therefore have different priorities when it comes to the nature of their work, the forms of knowledge privileged in specific settings/spaces, and the skills needed to be effective in those varied contexts. Various ways of knowing may be challenged within larger system structures and we argue that within our own cycles of collective-action-inquiry-reflexivity (praxis), no one position is of any greater value than another. All community psychologists, across disciplinary lines are important for revealing the oppressive mechanisms inherent in the system and organizing resources necessary to subvert or dismantle them. Working collaboratively and in alignment with this purpose is the future of the field. Each informs and can complement the work of others because the conditions of every work context limits activity, and what can be known.

We believe that integration or re-combinations across the continuum, to the extent possible, are more useful than hardening or polarizing distinctions between academic and practice or between science and practice. One person or team might engage in an inquiry project positioned very far to the post-positivist side of this continuum and also be engaged in other projects grounded in a philosophy of transformation, or work to uplift or preserve indigenous knowledge systems. Then again, CP projects may apply a variety of tools, with multiple intentions, including building generalizable or transferrable knowledge that builds capacity for system change. The main way the continuum of CP praxis can be helpful here is in clarifying the sets of assumptions embedded in the work of varying organizations, bringing more intention to identifying the power embedded within varying frames, and helping us to be intentional in bringing these data into dialogue that is intentionally more equitable within ongoing cycles of relationally ethical praxis.

Clarifying Relational Ethics in Praxis

“…epistemic decolonization is not sufficient: a radical change in forms of being, living, and acting in the world is also necessary.” (Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, in “Epistemic Extractivism: A Dialogue with Alberto Acosta, Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, and Silvia Rivera, by Ramon Grosfoguel; de Sousa Santos & Menses, 2020)

All knowledge gained from various projects along the continuum are valid forms of knowing, and through inclusion of varying perspectives, we are able to expand ecologies of knowledge considered within everyday decision-making (epistemic justice). The revised definition of CP practice also points to the value of developing and cultivating horizontally structured, relationship networks, or, at minimum, acknowledges the potential for harm embedded in relationships based on hierarchies. Vertical relationships can manifest in many ways, including, for example, extracting the data/stories from local communities and framing their community activism/labor within cognitive-based frameworks that potentially mischaracterizes the nature of their/our struggle. It is safe to say here, that all forms of regular praxes must be questioned as we have all been desensitized to the nature of harm normalized in daily practices. This is precisely why it is so important that we prioritize a relational ontology, grounded in empathy and care for all actors (human, non-human, living, non-living, through spiritual interconnectedness), and then see what possibilities emerge from that ethical standpoint. It is from this stance that we work to peel back all the ways we are, by default, often engaged in an ethic of domination and work towards an ethic of love (hooks, 1994).

The shift from the focus on a philosophy of science to a philosophy of action/science (i.e., praxis) is intentional in that this distinction indicates a shift in the approach all community psychologists take to their work. One that encourages an emphasis on ways of being based within deep appreciation, understanding of power and oppression, and care. Through this lens, community psychologists may need to stray beyond any comfortable personal ethics or moral bounds and instead engage in ways of being, and specific actions, that end suffering for life and allow for preservation of many forms of life. This calls for a deeper understanding of responsibility and enactment of accountable autonomy (See Vanessa de Oliveira Andreotti, 2021, book titled Hospicing Modernity: Facing Humanity’s Wrongs and Implications for Social Action).

Although CP is not a field that espouses a purely science orientation, as taught through mainstream education, the ideological bases of the professionalization of the field can unintentionally reinforce habits of being in relationship with community/life that tends to emphasize a superiority over others (e.g., cognitive superiority). While some CPs are intentional in the development of practices consistent with horizontal relationship-building, other norms embedded in the field continue to emphasize a more dominant cultural approach to inquiry (e.g., academic research, teaching, and mentoring norms). We understand these norms as suspect, and therefore are routinely scrutinized in our work. Traditional research and scholarship norms create harm through imposing theoretical frameworks over lived experiences of local communities, analysis, and compartmentalization or reductionism. That is how current science education encourages taking the world apart rather than understanding the world in terms of complex, interrelated social and ecological systems (Bateson, 1982; Datta, 2015).

The revised definition of CP practice articulated here is akin to the philosophy of Liberation Psychology, particularly in how we accentuate relational ethics (Martin-Baró, 1994; Montero, Sonn, & Burton, 2017). Our reconceptualization of CP praxis emphasizes relational ethics as the process of becoming one with complex adaptive systems of relationships within geographic regions, organizational settings, and community spaces, which involves a mutual, co-laboring, capacity-building process, predicated on ongoing conversations and co-learning with attention to differences in power and care for experiences of harm. This dovetails with liberation psychology literature on critical consciousness in action that indicates how intentional analysis of power within relationships is key to authentic dialogue that allows for liberatory transformation (Montero, 2009; Serrano-Garcia, 1994).

In our work, lengthy or ongoing dialogues are often prioritized to share/hear experiences and knowledge, which are praxes that have been long valued by social communities appreciating indigenous knowledges of the Global South. One example of this is how our university’s Civic Engagement Center is co-hosting a discussion session on the “Whose Lakefront” project with the Native American Center of Chicago. This is particularly important within the context of Chicago where oppression based largely on coloniality of power manifests through the living legacy of colonialism through racial, gendered, spiritual, political, and social hierarchical orders (Lugones, 2007; Quijano, 2000). These hierarchies have been the foundation for the design and ongoing functioning of the city as reflected in current social and economic structures (Nightingale, 2012). In addition, we believe acknowledging power dynamics is critical in that if we are in dialogue without acknowledging the global, historical context of subjectivities, and a frame of decoloniality, we may only be replicating discourses based on a hegemonic monologue. Therefore, unless we (multiple community stakeholders – academics included) understand how power dynamics influence our relationships, we will not be able to engage in the local dialogue necessary to bring all forms of knowledge into consideration when seeking to change harmful systems structures (e.g., public policy, organizational practices, normalized harmful ways of being in relationship to the world in general).

We view ourselves in ongoing dialogue with those of varying roles within our geographic and political landscape. We strive to better connect across obstructions of power to bridge new understandings that we hope can build to influence real social, cultural, and structural change. Our work to apply the variety of CP practice competencies is part of this praxis. To better participate in this relational praxis, we seek to enhance our understanding of what it means to be “in relationship.” Building horizontal relationships through an increasing understanding of how power manifests itself in relationships, we work to deepen our understanding of how various power dynamics influence our positions and processes.

Within our own geographic space (i.e., United States, Midwest, Chicagoland, urban setting) and in our attempt to reach and build expanded relationships globally, we believe that raising our deep structural, cultural, and political consciousness within our current context and settings, involves deliberate cycles of praxis on five main points related to all projects, including intention, purpose, positionality, power and relationality.

1. Intention refers to being clear with ourselves and others about why we seek to engage with a particular community or issue and our relationship to that community or issue. Questions to consider include:

2. Purpose refers to what we hope to achieve by engaging with others in a space. Questions to consider include:

3. Positionality refers to an acknowledgement of social, cultural, and institutional settings in which we are embedded, including aspects of our own human characteristics such as age, race, gender, residency, etc. Reflecting on positionality involves a close examination of the human characteristics we hold within our being and unpacking their meaning in the context of a specific historical and present setting (Harrell & Bond, 2006). Questions to consider include:

4. Power refers to an explicit analysis of how power is experienced by us and others as it relates to the three points above. This analysis includes examining and determining whether we hold integrative power, power to, power over, power with, or power from oppression (Neal & Neal, 2011; Serrano-Garcia, 1994). We believe this analysis of our power is tied to characteristics of our positionality and our relationality in every setting. Questions to consider include:

5. Relationality refers to the assumption of a relational ontology emphasizing an understanding that we are not spectators of reality but actors that are an interdependent part of this world, taking into consideration relationships with land, nature, and sustainability (Datta, 2015). It is important to understand the relationship we have to the settings/spaces in which we participate and the people, all of which is intricately tied to our positionality and power. It is through an analysis of our relationships that we learn ways to enact our agency for social, structural, and cultural change. Ultimately, relationships are of central importance to every aspect of our lives including our relationship to madra tierra. Questions to consider include:

Through a cycle of praxis on these five main reference points within every project, and varying stakeholders, we believe we are able to enact a model of CP praxis that allows for critical, liberatory, community building that also supports alternative settings grounded in the spirit of decoloniality (See: Global Journal of CP Practice Special Issue: Embodiment of Decoloniality, in press).

Implications for Education and Training

We end the current paper with a series of our own commitments and considerations for other community psychologists related to the promotion of this new and dynamic definition of CP practice. We also conclude with some recommendations for higher education more broadly.

1. Work Through Development of Relational Ethical Praxis – Through ongoing self-reflexivity within our pedagogy (through writing, teaching, discussions) on intentional global, historical, and decolonial analyses, we will work to make clear our intentions, purpose, positionality, power, and relationality, in all of our work and encourage these practices among other CP colleagues. We will prioritize educating about the importance of embodying cycles of praxis on these five main reference points within every project, including varying stakeholders within community partnerships and deliberative dialogues. We will explicitly embed these criteria within assessment of our dissertations and link it within the content of our courses: Mixed-Quantitative-Qualitative Methods, Advanced Cross-Cultural Communication, Prevention & Interventions, and Leadership and Organizational Change.

2. Acknowledge Critical Global Citizenship – We will seek to understand global history and its connections to local history and create opportunities for global community connections and learning. To promote community psychologists as planetary citizens, we will develop a resource for education programs to reference when considering educational opportunities transnationally, acting in alignment with others to address global injustices and allowing for potential cross-cultural inquiry/scholarship opportunities. We will aim to create spaces that assist us in identifying and gaining deeper understanding of the intangible belief systems that create and maintain structures of oppressive systems. To foster learning from our varied colleagues around the globe, we will participate in the creation of a consortium that focuses on transnational knowledge, development, and action. Inevitably this involves understanding how relational ethical praxis uncovers our positionality from a global historical frame.

3. Seek to Understand the Complexity of Whole Communities – This includes a variety of adjustments to our relationality and our worldview around connectedness similarly or differently than those of our colleagues:

4. Continuously Critically Analyze the Depths of our Local Historical Context and the Role of the University - As methodologists and co-learners/laborers with our students, alumni, and local communities, we will intentionally prioritize understanding how philosophies of action/science are embedded in local systems and how they shape dominant discourses and orientations to identified resources.

5. Intentionally Promote a Sense of Community in CP – We believe that enacting our strategies for building just, healthy, supportive, and vibrant community engagement also applies to our personal, professional, and educational communities (see Jimenez et al., 2016). Through enacting the new CP practice definition, we can better respect paradox and complexity within our field and address undercurrents of ideologies and belief systems negatively influencing social dynamics across contexts while building on our assets to improve our local and global well-being.

6. Continuously Improve the Definition of CP Praxis – Let us synthesize the current proposed changes to the definition of CP practice and continually take in feedback to change, improve, and consider the downstream effects of those changes on competency development, training, and actual sense of community. We are certain that essential ways of enacting relational ethics in professional spaces and settings will reveal themselves over time as we hope the social-political conditions shift as well.

Conclusions

As community psychologists, we attempt to ethically and judiciously shift the norms of our settings to create more of a collaborative, co-laboring, sharing spirit, rather than competition and any individualistic striving toward recognition. This more truly collective approach is the empowered path forward, the unapologetic stride of many new and diverse community psychologists in the field prepared to not only accept shifts towards more just work, but to be the shift. And yet the norms of the field may at times leave some of community psychologists afraid to freely share ideas, fearful of not receiving credit for our work and ideas in an academic world that very much replicates masculine, capitalistic worlds striving after power and dominion. Let’s put a stop to those tendencies that reduce our chances of creating a world to which we all aspire to belong (Jimenez, 2018). We aim to step away from competitive individualism passed on to current cultures via Western imperialism. We do so by reducing judgments and by valuing the diverse work and perspectives of our colleagues working in and around various organizational contexts. We create shared spaces and learning communities within local contexts, across whole continents, and across the globe. We work to build more of a sense of community across our roles and identify how the inquiry in which we are each engaged, contributes to a more in-depth understanding of reality. We hope this conceptualization of a cyclical CP praxis continuum helps better aim the development of the field to actively promote justice, healing, and wellness among the various communities we inhabit and engage, as well as more firmly engaging in vigorous dialogue with the power structures that are otherwise poised against progressive social change.

NOTES

[1] Acknowledgements: We thank Christopher Sonn, Cari Patterson, Moshood Olanrewaju, Aaron Baker, Ramy Barhouche, Gorden Lee, and Raphael Kasobel for their early input and reviews of this paper over the last year.

[2] We proposed a draft definition during a special session of the 2020 Midwestern ECO conference. A wealth of perspectives and important understandings influenced what was proposed and this generated further revisions.

[3] Use of the term “whole” to refers to a concept of communities that includes all aspects of place and how people relate to all elements of their place. This is not to be confused with borders imposed on communities such as city, state, or other political lines drawn within and across geographic community areas.

[4] The term “spaces” refers to the places we gather outside of existing system-designed settings such as non-profits, for-profits, large/small organizations, designated centers, and institutions. Spaces are created, abide by the relational needs of those in attendance, and flow like water. Spaces may either occur online or in-between existing settings (e.g., online spaces, personal spaces, creative spaces, natural spaces) where created relational norms exist, for as long as they are needed.

References

Anzaldúa, G., & In Keating, A. L. (2015). Light in the dark: Luz en lo oscuro: rewriting identity, spirituality, reality. Duke University Press.

Bateson, G. (1982). Gregory Bateson: The Legacy of a Scientist by David Lipset.

Bennett, C.C., Anderson, L.S., Cooper, S., Hassol, L., Klein, D.C., & Rosenblum, G. (Eds.) (1966). Community psychology: A report of the Boston Conference on the education of psychologists for community mental health. Boston: Boston University Press.

Bhaskar, R. (2002). From Science to Emancipation: Alienation and the Actuality of Enlightenment. The Bhaskar series. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Caouette, D. & Kapoor, D. (2016). Beyond Colonialism, Development and Globalization. London: Zed Books.

Crass, C. (2013). Towards Collective Liberation: Anti-racist Organizing, Feminist Praxis, and Movement Building Strategy. Oakland: PM Press.

Datta, R. (2015). A relational theoretical framework and meanings of land, nature, and sustainability for research with Indigenous communities. Local Environment, 20(1) ,102-113.

Denzin, N. K. (2009). The elephant in the living room: or extended the conversation about the politics of evidence. Qualitative Research, 9:139.

de Sousa Santos, B. (2007). Beyond Abyssal thinking: From global lines to ecologies of knowledge. https://www.eurozine.com/beyond-abyssal-thinking/

de Sousa Santos, B. (Ed.), Meneses, M. P. (Ed.). (2020). Knowledges Born in the Struggle. New York: Routledge, https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429344596

Escobar, A. (2017). Designs for the Pluriverse: Radical Interdependence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds. Durham; London: Duke University Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctv11smgs6.4

Escobar, A. (2020). Pluriversal Politics: The Real and the Possible. Durham; London: Duke University Press.

Evans, S. D. (2014). The Community Psychologist as Critical Friend: Promoting Critical Community Praxis. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, n/a-n/a. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.2213

Fadiman, A. (1997). The spirit catches you and you fall down: A Hmong child, her American doctors, and the collision of two cultures. Farrar, Straus, and Giroux.

Drolet, B. & Lorenzi, N. M. (2011). Translational research: Understanding the continuum from bench to bedside. Translational Research, Vol 157, Issue 1; pages 1-5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trsl.2010.10.002

Freire, P. (2014). Pedagogy of the oppressed: 30th anniversary edition. ProQuest Ebook Central https://ebookcentral.proquest.com

Gergen, K. J. & Zielke, B. (2006). Theory in Action. Theory & Psychology, 16: 299. DOI: 10.1177/0959354306064278

Gone, J. P. (2007). “We Never was Happy Living Like a Whiteman”: Mental Health Disparities and the Postcolonial Predicament in American Indian Communities. American Journal of Community Psychology, 40:290-300. DOI 10.1007/s10464-007-9136-x

Grosfoguel, R. (2020). Epistemic Extractivism: A Dialogue with Alberto Acosta, Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, and Silvia Rivera. In de Sousa Santos, B. (Ed.), Meneses, M. P. (Ed.). (2020). Knowledges Born in the Struggle. New York: Routledge, https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429344596

Harrell, S.P., Bond, M.A. (2006). Listening to Diversity Stories: Principles for Practice in Community Research and Action. American Journal of Community Psychology 37, 365–376. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-006-9042-7

hooks, b. (1991). Theory as Liberatory Practice, 4 Yale J.L. & Feminism.

Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/yjlf/vol4/iss1/2

Hopner, V. & Liu, J. H. (2021). Relational ethics and epistemology: The case for complementary first principles in psychology. Theory & Psychology, 31(2), 179-198.

Horton, M. & Freire, P. (1990). We Make the Road by Walking: Conversations on Education and Social Change. Temple University Press. 190-240.

INCITE! (2017). The Revolution Will Not Be Funded: Beyond the Non-Profit Industrial Complex. Cambridge, MA: Duke University Press.

Israel, B. A., Schulz, A. J., Parker, E. A., & Becker, A. B. (1998). Review of Community-Based Research: Assessing Partnership Approaches to improve Public Health. Annual Review of Public Health, 19:173-202.

Jimenez, T. R. (2018, July). To Liberate and be Liberated with: A Commitment to Realizing Freedom. American Evaluation Association – AEA 365 Blog. See: https://aea365.org/blog/to-liberate-and-be-liberated-a-commitment-to-realizing-freedom-by-tiffeny-jimenez/

Jimenez, T. R. (2012). Attending to Deep Structures: Exploring How Organizational Culture Relates to Collaborative and Network Participation for Systems Change. Dissertation: Michigan State University Library.

Jimenez, T. R. (2020, June 3). A Checklist Towards Decolonizing the University. https://tiffenyjimenez.wordpress.com/blog-2/

Jimenez, T.R. & Barhouche, R. (2021). Uncovering Ideologies of Colonialism: Assessing Collaborative Systems Using Critical Community Psychology. Sixth International Culturally Responsive Evaluation and Assessment (CREA) Conference. Interrogating Cultural Responsiveness Against the Backdrop of Racism and Colonialism. Chicago, IL

Jimenez, T. R., Sanchez, B., McMahon, S.D. & Viola, J. (2016). A vision for the future of Community Psychology education and training, American Journal of Community Psychology, 0: 1-9. doi:10.1002/ajcp.12079

Kivel, P. (2016). Social Service or Social Change? In Navigating neoliberalism in the academy, nonprofits, and beyond. The Scholar & Feminist Online, 13.2, SPRING 2016: https://sfonline.barnard.edu/navigating-neoliberalism-in-the-academy-nonprofits-and-beyond/paul-kivel-social-service-or-social-change/0/

Lugones, M. (2007). Heterosexualism in the Colonial/modern Gender system. Hypatia, 22(1).

Machado de Oliveira, V. (2021). Hospicing Modernity: Facing Humanity’s Wrongs and the Implications for Social Activism. Berkley, CA: North Atlantic Books.

Maldonado-Torres, N. (2007). On the Coloniality of Being: Contributions to the development of a concept. Cultural Studies, 21:2, 249-270.

Marsella, A. J. (1998). Toward a “Global-Community Psychology”: Meeting the Needs of a Changing World. American Psychologist, 53(12); 1282-1291.

Martín-Baró, I., Aron, A., & Corne, S. (1994). Writings for a liberation psychology. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

Mbembe, A., & Corcoran, S. (2019). Necropolitics. Durham: Duke University Press.

McKittrick, K. (Ed.). (2015). Sylvia Wynter: On Being Human as Praxis. Durham; London: Duke University Press. DOI:10.2307/j.ctv11cw0r

McMahon & Wolfe (2016). Career opportunities in community psychology. In M. Bond, I. Serrano-Garcia, & C. Keys (Eds.), Handbook of community psychology: Volume II. Washington D.C.: American Psychological Association.

McMahon, S. D., Jimenez, T. R., Bond, M. A., Wolfe, S. M. & Ratcliffe, A. W. (2015). Community psychology education and practice careers in the 21st century. In V.C. Scott & S. M. Wolfe (Eds.), Community psychology: Foundations for practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Mignolo, W. D. & Walsh, C. E. (2018). On Decoloniality: Concepts, Analytics, Praxis. Durham: Duke University Press.

Montero, M., Sonn, C. & Burton, M. (2017). Chapter 7: Community Psychology and Liberation Psychology: A Creative Synergy for an Ethical and Transformative Praxis. In APA Handbook of Community Psychology, Volume 1: Theoretical Foundations, Core Concepts, and Emerging Challenges. (Eds.) Bond, M., Serrano-Garcia, I. Keys, C. B. American Psychological Association.

Morales, S. E. and de Almeida Freire, L. (2017). Planetary citizenship and the ecology of knowledges in Brazilian universities. International Journal of Developmental Education and Global Learning, 8(3), p DOI: https://doi.org/10.18546/IJDEGL.8.3.03

Mungwini, P. (2019). Symposium: Why Epistemic Decolonization. Journal of World Philosophies, 4 (Winter): 70-105.

Neal, W. & Neal, P. (2011). Power as a Structural Phenomenon. American

Journal of Community Psychology, 48: 157-167. DOI 10.1007/s10464-010-9356-3

Nightingale, C.H. (2012) Segregation: A Global History of Divided Cities. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Norsworthy, K. L. (2007). Mindful Activism: Embracing the Complexities of International Border Crossings. American Psychologist, 72(9), 1035-1043.

Olson, B.D. & Jason, L. A., (2015). Participatory Mixed Methods Research. The Oxford Handbook of Multimethod and Mixed Methods Research. Ed. Hesse-Bieber and Johnson. Oxford University Press.

Olson, B. D., O’Brien, J. F., & Mingo, E. D. (2019). In eds. Jason, L.A., Glantsman, O, O’Brien, J. F., & Ramian, K. N. Introduction to Community Psychology: Becoming an Agent of Change. Free online textbook.

Olson, B., Viola, J., & Fromm Reed, S. (2011). A Temporal Model of Community Organizing and Direct Action. Peace Review.

Pitts, A., Ortega, M. & Medina , J. (2020). Theories of the Flesh: Latinx and Latin American Feminisms, Transformation, and Resistance. Oxford University Press.

Quijano, A. (2000). Coloniality of Power, Eurocentrism, and Latin America. Nepantla, Views from the South, 1(3): 533–580. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 June 2012.

Reich, S.M., Riemer, M., Prilleltensky, I. & Montero, M. (2007). International Community Psychology History and Theories. New York: Springer.

Reich, S.M., Bishop, B., Carolissen, R. Dzidic, P.,Portillo, N.,Sasao, T. & Stark, W. (2017). Catalysts and Connections: The (Brief) History of Community Psychology. In APA Handbook of Community Psychology, Volume 1: Theoretical Foundations, Core Concepts, and Emerging Challenges. (Eds.) Bond, M., Serrano-Garcia, I. Keys, C. B. American Psychological Association.

Reiter, Bernd (ed.) (2018). Constructing the Pluriverse: The Geopolitics of Knowledge. Duke University Press.

Renz, D. O. & Associates (2016). Jossey-Bass Handbook of Nonprofit Leadership and Management (4th Edition). John Wiley & Sons, Inc., San Francisco, CA.

Throughout the World in Bond, M.A., Serrano-Garcia, I., & Keys, C. B. (Editors in Chief). APA Handbook of Community Psychology: Vol 1. Theoretical Foundations, Core Concepts, and Emerging Challenges. New York: Kluwer Plenum.

Reuters (October, 25, 2020), “Meet the man ‘seizing’ African art from Western Museums”: https://youtu.be/UAYhRUj9VOI

Rojas, C. (2016). “Contesting the Colonial Logics of the International: Toward a Relational Politics for the Pluriverse.” International Political Sociology 10 (4): 369–82.

Ruti, M. (2015). The age of scientific sexism: How evolutionary psychology promotes gender profiling and fans the battle of the sexes. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Sarason, S. (1974). The Psychological Sense of Community: Prospects for a Community Psychology. The Jossey-Bass behavioral science series. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers. ISBN 978-0-87589-216-0.

Sarason, S. B. (1978). The nature of problem solving in social action. American Psychologist, 33(4), 370–380.

Sarkisian, G. V., Saleem, M. A., Simpkin, J., Weidenbacher, A. Bartko, N. & Taylor, S. (2013). A Learning Journey II: Learned Course Maps as a Basis to Explore How Students Learned Community Psychology Practice Competencies in a Coalition Building Course. Global Journal of Community Psychology Practice, 4(4).

Teo, T. (2010). What is Epistemological Violence in the Empirical Social Sciences. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 4/5: 295-303.

Tucker, K. (2018). Unraveling Coloniality in International Relations: Knowledge, Relationality and Strategies for Engagement. International Political Sociology, 12: 215-232.

Yakushko, O. (2019a). Eugenics in History of American psychology. Psychotherapy and Politics International

Yakushko, O. (In Press). In Science We (Should Not Always) Trust: Decolonizing the Science of Psychology. Global Journal of Community Psychology Practice, Special Issue on Embodiment of Decoloniality.

Fig. 1: A Continuum of Community Psychology Praxis |

Tiffeny R. Jiménez, Ericka Mingo, Judah Viola, Bradley Olson, & Christopher Balthazar

Tiffeny R. Jiménez, Ericka Mingo, Judah Viola, Bradley Olson, & Christopher Balthazar

Tiffeny Reyleen Jiménez Community Psychologist. Educator. Her story is rooted in indigenous Americas-México traversed through terrains of Turtle Island known as California into the Midwest U.S. Being mixed heritage, she views the world and relates as a borderlands survivor, rajetas y sin fronteras, queer, alternative world compost-activist.

Currently, she is most interested in how to support spaces for communicative justice using mixed and creative methodologies, developing strategies for embodying praxes of decoloniality, and engaging in collective action scholarship via liberation-oriented andragogy/pedagogy towards transformative systems change. She participates in action/service praxis enacting an ecologically grounded institutional philosophy of scholarship that connects authentic student voice and inquiry with streams of public scholarship to shape our public sphere using multi-modalities. She is also the internal collaborative evaluator for CLAVE: Colaborando con las Comunidades Latinx para AVanzar en Educación / Collaborating with Latinx Communities to AdVance Education, which supports doctoral student fellows and postdocs across disciplines.

Tiffeny is the recipient of the 2019 National Louis University (NLU) Excellence in Research, Scholarship, and Inquiry Award, and is currently working to co-develop the ideological infrastructure needed to support ethical and deliberate community engagement across NLU for communities we serve in the Chicagoland area and beyond. She is most active in co-developing Critical Global Education for Community Psychology (https://criticalglobaleducation.wordpress.com/), co-developing the cultural community of Xicanx Psychology – Institute of Chicana/o Psychology (https://razapsychology.org/), learning with The Rooted Global Village (https://www.rootedglobalvillage.com/), supporting The Emergence Network (https://www.emergencenetwork.org/), and reflecting with others of the Society for Community Research and Action (https://www.scra27.org/). For more information see: https://tiffenyjimenez.wordpress.com/

Add Comment

![]() Download the PDF version to access the complete article.

Download the PDF version to access the complete article.

Keywords: community psychology, practice, action, relationational ethics