The saying is that each generation is supposed to do better than the generation before it. I was told that we can never live the “American Dream” if we do not go to college, get a good-paying job, and buy a home. The question is, why are these human rights accessible for some and a struggle for others? I want to tell you about the history of my family’s survival. This story is important because it has blazed a trail for four generations of my lineage to live differently from our ancestors. Each generation has a painful but beautiful story of endurance. It could be a roadmap for so many fighting families. The purpose of my story is to bring awareness of the Black struggle and survival. I understand the journeys of my lineage and I would like to make a suggestion. We must learn who we are, where we come from, where we want to go, and how to get there, which would be based on our own sense of stability in a decolonized village.

Please click here to download the PDF of this article.

Prologue

It has been a long journey. Feeling like I belong was/is always important to me, it is part of myidentity. Knowing where and who I come from, being linked to my family, having a place to callhome, and planting my seeds have fulfilled me. I have experienced that sense of belonging,needing to connect, understand, have a purpose, and be satisfied. The consciousness of my life,my lineage, our thrive to survival, their presence in me, and our journey from the beginning tothe present day are alive. My lineage’s determination has grown and evolved since Mississippi,and I have learned who I am. As I reflect on my/our journey in this article, what we experiencedis awareness and consciousness as we encounter oppression and displacement. We understandself-value and the love of self-created self-activism and that space to resist all things that are notjust. What has emerged can be described in three theoretical concepts:

“You can’t really know where you are going until you know where you have been.” – Maya Angelou

This writing tells the story of my ancestors’ survival and their fight for freedom. They fought for housing and the right to be safe; I am fighting to secure and improve their legacies. Although the “American Dream” remains dominated by colonialism and trauma, my ancestors were creative, rebellious, and resilient, to name a few of their survival skills. My strength is inherited; it’s a skill of my family. They took dangerous risks to change the trajectory of their situations and those of future generations through their conscious and unconscious actions. I live because of their self-activism. They wanted not only to survive but to thrive and to secure an equitable quality of life. I have learned that equity includes community stability, psychological freedom, protection, healing, resources, and homeownership. Stability includes stopping the historic pattern of “Black mobile communities” and preventing the colonizer’s patterns of interrupting our Black family.

Thesis Nine - “Decoloniality involves an activist decolonial turn whereby the damné emerges as an agent of social change.” (Maldonado-Torres, 2016, p. 28)

Village and Community

I have heard a few “Black Baby Boomers” talk about their upbringing, and they often used the term “village.” They define a “village” as a place where people looked out for one another and stuck together. They shared how the adults in the village would discipline them for their behavior and inform their parents about their mischief. When I was a child, I remember calling my neighbors “cousin” and our friends having meals at our home and traveling with us. I remember my mother’s moral value system and how it grounded her children. Although my mother never used the term “village” in our home, nor did I hear it in my community, for a brief time I felt it. We were taught that we are our brothers and sisters’ keepers, to love each other and our neighbors. We have built on her moral values, incorporated education, homeownership, and community. We’ve passed them on to our children, and they continue to build on them. Her grandparents and mother claimed the land, and she laid the foundation. Her children understand that we won’t stand strong on any foundation until we plant seeds. This requires strong “whole families” or villages to work together to plant more seeds while decolonizing our “community.”

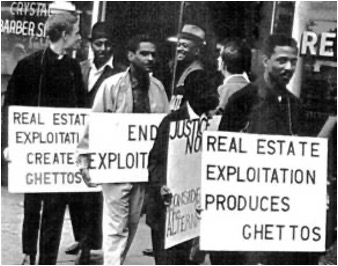

The dictionary definition of a village is a place where people come to settle and to build a community. I often wondered what determined a village. In the context of this article, the term “village” will refer to the connections people make when living together as a family with the land, and “community” will refer to the development structures that are built over time within the context of a specific geographic, historical, and political location. This article talks about my village and community experiences within the settler-colonial geographic area referred to as the United States (see Barker & Lowman, n.d., for more information on settler colonialism). Within the United States, Black villages were referred to as ghettos—parts of a city, especially slum areas, occupied by a minoritized group or groups—and put in or restricted to an isolated or segregated area or grouping. This was the housing experience of Black people migrating from the South during WWI and WWII. Today, Black families continue to face housing discrimination in the City of Chicago.

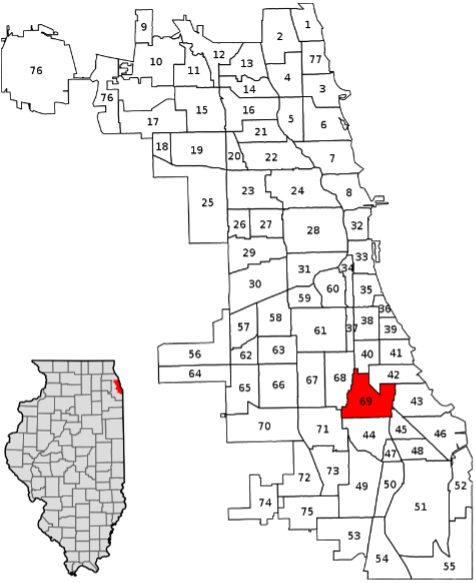

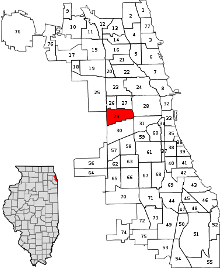

More than a decade ago, I relocated to Park Manor, a smaller community within the Greater Grand Crossing area on the Southside of Chicago (see map of Chicago, neighborhood #69 Image 1; Wikipedia, 2022c).

It borders the once-bustling Black Chatham community (see map of Chicago, neighborhood #44), which does not fit the description of a ghetto (Wikipedia, 2022d).

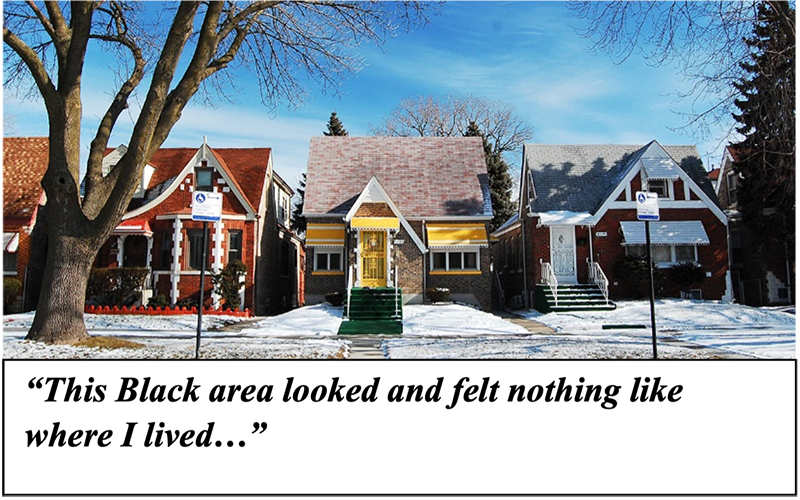

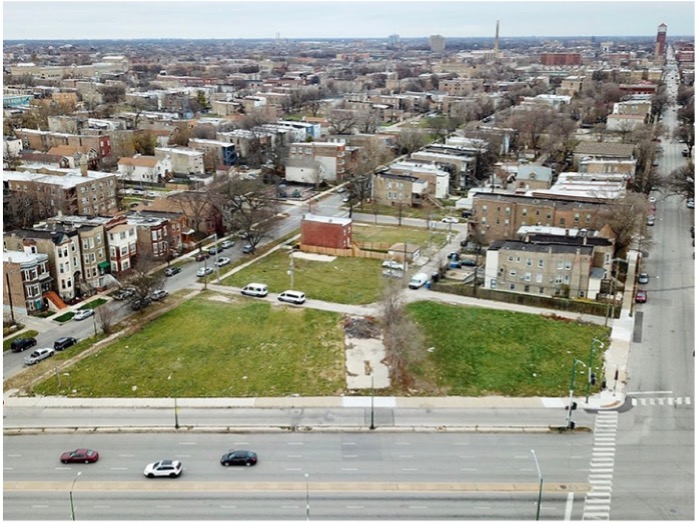

I experienced Chatham while attending high school in the mid-1980s. This is a place where several of my friends from high school live(d), and what I did not understand at that time was that I had been introduced to a highly functioning Black community. My Chatham friends were full of life and so was their community, as there were thriving Black-owned businesses and rows of occupied homes, beautiful landscaping, and peace. This Black area looked and felt nothing like where I lived, the audacity of me to want my village to experience that community. I was certain that my future community would resemble Chatham (O’Beirne, 2019).

See Image 2: Chatham Neighborhood

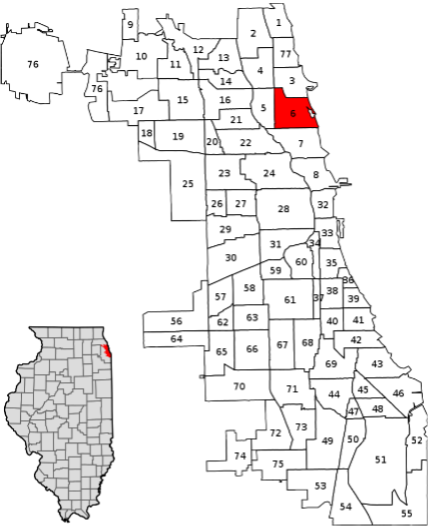

In the mid-1990s, I relocated to the Lake View area on the Northside of Chicago (see map of Chicago neighborhood #6 Image 3) and experienced another bustling and thriving community.

Predominantly White and different from Chatham, it is rich in resources, services, businesses, various styles of homes, trees, and stuff that I didn’t know that I needed or wanted (Lakeview East Chamber of Commerce, n.d.; Wikipedia, 2022e). Both looked or felt nothing like my predominantly Black, Southside community within the larger Bronzeville community.

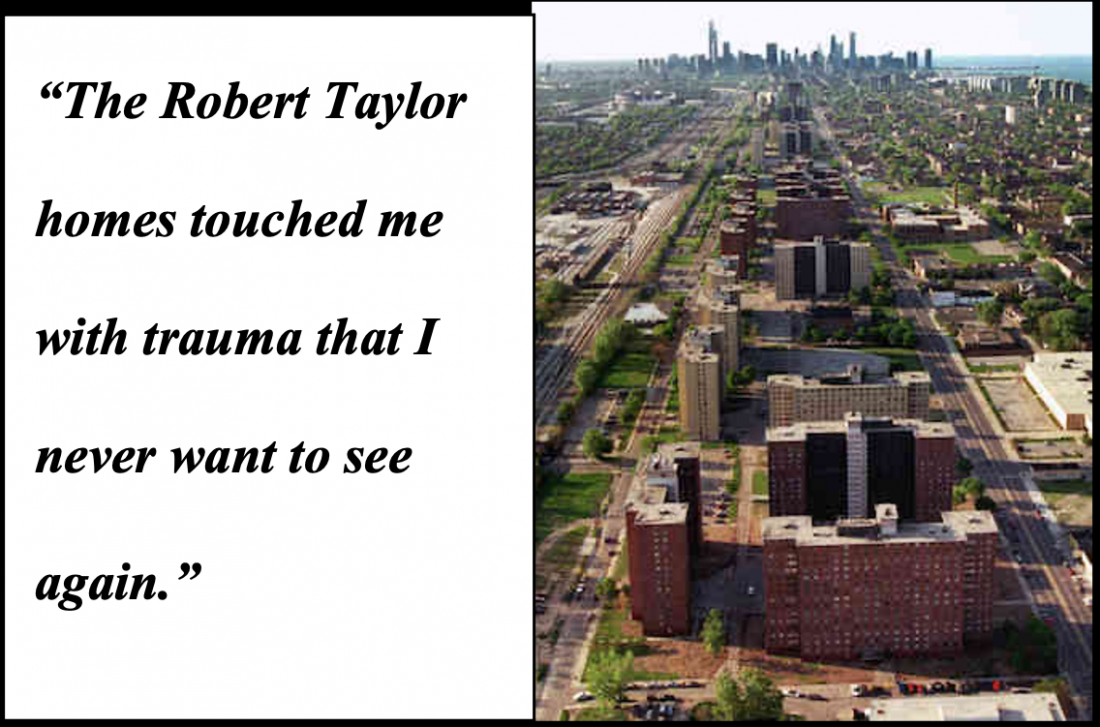

The Robert Taylor homes (African American Registry, n.d.) touched me with trauma that I never want to see again. We endured experiences that no family should ever have to live through. I lived in a war zone for 10 years. I lost many classmates to drugs, gangs, prison, and death. Families separated before my eyes and children didn’t return home. When my ancestors arrived from the South in search of their village, I am sure they hoped that their future generations would not have to go through what they had gone through. History repeats itself but it doesn’t have to, and I hope that telling our stories will inspire other Black people to become self-activists and fight for their villages and communities.

The Roots of Self-Activism

I love myself, my dark skin, and everything about me but being Black, and what comes with being Black is trauma all by itself. My great-grandparents were born in Mississippi between the 1870s and 1890s. They lived in the times of the movement of social activism and political reform (the late 1890s to the 1920s). This was known as the Progressive Era that was taking place across the nation and the continuous racial segregation (Jim Crow Laws) that swept the Southern states. The trauma that they had to live with is unthinkable. After learning of higher wages and less racial tension described and advertised by the Chicago Defender, a Black-owned newspaper, they seized the opportunity to start over. They married, relocated to Arkansas in the 1920s, gave birth to my grandmother, and moved to Chicago seeking a better life (Greetham, 2013, p. 21). At the time that my grandparents were in Chicago, they were unable to buy any homes, which is what we continue to experience today. Therefore, even though my great-grandfather found a good-paying job and was able to rent housing in his community, he was not able to purchase a home because he was “redlined,” which is a form of housing discrimination that prevented Black families from buying homes outside of more common areas designated for Black communities (Greetham, 2013, p. 92). My great-grandparents, grandmother, and mother could not buy where they lived, and this continued the pattern of displaced living—as a mobile village. Two generations were forced to relocate, but they were survivors, practicing self- and collective activism toward a vision of a better life. My mother’s children are the first generation to weave ourselves out of this housing oppression.

In 1952, my great-grandfather and grandmother worked for Illinois State Representative Vito Marzullo. In 1953, they supported Marzullo’s Alderman campaign by canvassing for him as he ran for the City of Chicago’s 25th Ward, the North Lawndale community. My family helped Mr. Marzullo secure the Black vote to win the seat. Alderman Marzullo supported Richard J. Daley’s mayoral candidacy, and in 1955 Daley was elected mayor of Chicago. Keeping his promise to build housing for Black families, he created the Black Chicago Housing Authority (CHA), which segregated housing on less desirable land (Choldin, n.d.). Several Black communities were built in what were considered the most undesirable areas of Chicago at the time. Built in 1962, the nation’s largest public housing development was the Robert Taylor Homes (Bowly, 1978). This public housing project was the largest in the world.

While my great-grandparents and grandmother were engaged in collective activism and fought for Black people’s justice, my mother was practicing self-activism as she fought for herself. My mother called the area of North Lawndale home from the 1940s until the early 1970s, and here is where she created her survival skills (Wikipedia, 2022b). As a child, she experienced much trauma both in her

community and at home, acts that hurt the Black village and Black community to the present day. Like so many people, my mother was physically and sexually abused in her home by relatives. When she fought back against her attackers she was locked in closets and starved. My mother shared that every day and night she prepared herself for a fight. When she arrived home acting furious, she would walk in the house screaming and yelling until she entered her room. As she got older, her family members called her crazy and stopped interacting with her. North Lawndale was a very white colonial community when she was growing up. This is where she was mentally abused. My mother stated that when she was in kindergarten, her white teacher would call on her using racial slurs and call her derogatory names. Regardless of the mental anguish my mother suffered, although she was an honor roll student, her teacher wanted to show my mother that she had the power over her and retained her in kindergarten. Fortunately, after my mother finished the first grade she doubled, skipping the second grade and putting her with her regular third-grade class. My mother stated that many things happened in this community, but because she volunteered as a crossing guard, volunteered at the school library, read to the lower grade children, and played sports, she was known, but not accepted because she was Black.

My mother was a teen when the Lawndale area experienced “White Flight,” (White people relocating from “communities” after Black people began moving in) and the businesses left too. By the 1960s, it had gone from a resourceful community to a slum (Taylor, 2010). In 1968, the day of Dr. Martin Luther King’s assassination, fires were set to many of the existing businesses, and the community was destroyed. The community fell into dilapidated condition, another factor adding to the high crime, drugs, and gangs. The rebuild did not happen; this was a factor that supported my family’s decision to leave.

My parents moved us to the CHA’s Robert Taylor homes in the early 1970s when I was a very young child (Wikipedia, 2022a). This was a colonial community within the Bronzeville community area of Chicago (Wikipedia, 2022f), the community in which I lived until I was a young adult. My memories about this place do not capture nor reflect the definition of any community, nor is it my idea of a Black community. Among various other disparities, we had minimal access to vital resources and services. I have had a lot of experience with the colonizer’s concept of a community, and it has not included the inherent values within my concept of the village. In the mid-1980s, I witnessed the colonizer destabilize the Black villages and our community, separating us and forcing us to live in mobile communities (for a video telling more about the raw truth of the Robert Taylor experience, see McQuilling, 2022); but the pursuit of freedom is worth fighting for.

Protecting the Village and Decolonizing Our Community

There is something powerful about watching the actions of happy people. Making people smile or feel good about themselves and their families has always been my desire since I was a child. Today, this is my life work. I come from a large loving family; we look out for one another and our neighbors. This is the village that I often hear Black people describe. I believe in supporting people, fighting for people’s rights to self-sufficiency, and connecting them to resources and services that will continue to help them sustain. Regardless of skin color, every person has the right to an equitable quality of life. In 1953, Mayor Richard J. Daley fulfilled two bad promises he had made. He expanded the existing CHA by keeping white low-income housing white, as he built Black segregated low-income housing. The Black Chicago housing complexes were placed in undesirable and undeveloped areas in the city. Undesirable areas do not attract businesses, and neither did Black people, limiting resources and services in our communities.

This practice continues today. To change how we are serviced, we must change who serves us. We must decolonize our communities by changing the programs, resources, services, and businesses in ways that reflect our values. As long as we allow the colonizer to dictate our community, we lose control of our village. We can no longer live according to the dictionary’s definition of the village. Until we understand how powerful self-activism is and how to use it, we will never achieve psychological freedom and we will continue to live in colonial villages. We must fight for our villages, we must use what we have access to, we must be creative, and we must push back.

My mother’s story will always be a mystery to me; she did something that she can’t explain. Her actions changed her children’s future, protected us, and helped her raise what I define as a village. She was, and is, a self-activist. Her decision to defend herself was not normal at her age, and not wise to do. She was determined to stop her pain, never to live it again or talk about it with her children was the answer to breaking the generational cycle of trauma. We must be determined to stop our villages from suffering at the hands of any colonizer. We must also decolonize our Black communities. My definition of a Black decolonial community (a community that is decolonized) is the right of families to live in a thriving community, defined by the ways of being that align with our vision. What does this look like? We have to free ourselves psychologically, strengthen as a village and push toward building our community. There is a choice you can make, but we don’t have to live in a colonized community. The more we make our Black families aware of their choices, and the consequences of their choices, the sooner we can rid ourselves of the problems laid upon us. The family is the foundation of the community; it is the whole family bonded or mended by love and unity. We are our brothers and sisters’ keepers, and without collective support we cannot survive or sustain, nor can a community thrive. Families build communities by connecting to the land that we belong to, the place where we can truly call home and plant our seeds on our land.

My great-grandparents and grandmother understood the importance of keeping their village together, but my mother unconsciously showed her children how to build healthy villages and keep them safe. While their self-activism helped to secure housing for Black villages, her self-activism helped her push back against abuse. She found safe spaces for herself, that helped her escape and grow; these were her resources. You cannot build a “healthy village” unless you can control generational trauma. She survived her mental strongholds, freeing her children from the way she lived and from the trauma she suffered. The saying, “only the strong survive” has truth to it.

It has been a few years since I learned the story of my family’s past, their journey, struggles, and contributions. I know that they would be proud of their grandchildren; we followed their path. Generations two and three reaped the benefits of the housing that my great-grandparents and grandmother fought for. Generations three, four, five, and six reap the benefits of our ancestors’ activism. We achieved the so called “American Dream” and purchased land. I secured my village, but this was no easy journey. I see them in me, like my Robert Taylor, Chatham, and Lake View experiences, their Southern and North Lawndale experiences cultivated our collective and self-activism. The struggles each of our communities suffer(ed) could have been manageable if the villages were strong. The oppressor went after the Chatham community, but their villages remain strong. To this day they continue to push back against separation. As their businesses closed, they added resources filled the void. The Lake View community is strong, and their villages are unified. The oppressor moves quickly to root out their disruptions, restore and heal the white villages with plentiful resources and services. Support systems help keep their families grounded; rarely are their villages mobile by force. The Robert Taylor community fell victim to the oppressor—businesses closed, few were replaced, and villages were divided and broken.

I experienced a connection to the Greater Grand Crossing community. It felt and looked like Chatham but after settling in, merely a few years later the oppressor has arrived. I have seen this face before, and I am ready to support the Black villages to save the Greater Grand Crossing community. We have the right to have stable homes, not mobile like many of our ancestors, and we have the right to keep what is already ours. The right to be safe, to be healthy, and to live in peace is what everyone is entitled to; it is our human right. Psychological freedom and homeownership are just a couple of things that balances a village, resources and services help to achieve self-sufficiency and sustainability. We must learn to create opportunities that help us thrive and live. Déjà vu. I see the dismantling of this community approach. The oppressor has the spotlight shining, and they continue to maliciously separate Black villages by taking their generational property and pushing them back into mobile living. We are not separate and unequal to any other community. This community does not have the resources and services of Lake View and the unity of Chatham, but similar struggles of Robert Taylor. All my adult life, I longed for a place to belong and people to connect with, and I refuse to watch the families in my community be uprooted and lose stability.

We know through painful experience that freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed. (King, 1963)

I know through personal and professional experiences that resources and services save families and communities. My great-grandparents’ and grandmother’s resources were employment and housing. My mother’s resources and services were school, sports, and self-defense. My resources are employment agencies, educational institutions, culture, child, youth, and adult activities, health care and hospital facilities, a variety of businesses, real grocery store options, and religious institutions, just to name a few. Communities with access to stimulating goods provide families with the tools to achieve psychological freedom and take control of their lives. Respect is not given but earned; my future generations must keep fighting for unity, community access, and peace.

If you can control a man's thinking you do not have to worry about his action. When you determine what a man shall think you do not have to concern yourself about what he will do. If you make a man feel that he is inferior, you do not have to compel him to accept an inferior status, for he will seek it himself. If you make a man think that he is justly an outcast, you do not have to order him to the back door. He will go without being told; and if there is no back door, his very nature will demand one. (Woodson, 2010, p. 45)

I am at the beginning of building my community. It is difficult to claim the land and build on the foundation if I don’t have a seed plant. We must retire the mobile family village. If we plant seeds on someone’s property, the legacy of colonialism and the constant uprooting and disruptions of our villages will continue to take our land. Homeownership helped me to be able to put roots down. I look at it as developing generational wealth. I introduced this concept to my family.

I didn’t like moving and I bought land, so we didn’t have to move again. When I purchased my land, I planted our seeds, and now I’m watching the growth of my children. My responsibilities in building my community in the 21st century are: bringing awareness of colonial systems, highlighting harmful generational norms, healing from generational trauma, bringing awareness to illegal family practices, removing stigma, obtaining psychological freedom, purchasing and retaining our land, investing in and developing social enterprises, and building coalitions or partnerships that create systems that meet the needs of the Black village and the Black community.

References

African American Registry (n.d.) Mon., 03.05.1962: The Robert Taylor Homes open. Retrieved March 22, 2022, from https://aaregistry.org/story/the-robert-taylor-homes-opens/.

Barker, A., & Lowman, E. B. (n.d.) Settler colonialism. Global Social Theory. Retrieved March 22, 2022, from https://globalsocialtheory.org/concepts/settler-colonialism/

Bowly Jr., D. (1978). The poorhouse: Subsidized housing in Chicago. Southern Illinois University Press.

Choldin, H. M. (n.d.) Chicago Housing Authority. Encyclopedia of Chicago. Retrieved March 22, 2022, from http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/253.html

Greetham, D. T. (2013). Chicago’s wall: Race, segregation and the Chicago Housing Authority (Paper 3801) [Senior independent study thesis, College of Wooster]. Open Works. https://openworks.wooster.edu/independentstudy/3801

Herman, J. L. (2015). Trauma and recovery: The aftermath of violence—from domestic abuse to political terror. Basic Books.

King, M. L. (1963). King’s letter from Birmingham jail. https://www.facinghistory.org/resource-library/letter-birmingham-jail

Lakeview East Chamber of Commerce. (n.d.) Getting around. Retrieved March 26, 2022, from https://lakevieweast.com/getting-around/

Maldonado-Torres, N. (2016). Outline of ten theses on coloniality and decoloniality. Franz Fanon Foundation. https://fondation-frantzfanon.com/outline-of-ten-theses-on-coloniality-and-decoloniality/

McQuilling, M. (2022, March 16). Robert Taylor Homes. The Hal Baron Project. https://halbaronproject.web.illinois.edu/items/show/44

Modica, A. (2009, December 19). Robert R. Taylor Homes, Chicago, Illinois (1959-2005). Black Past. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/robert-taylor-homes-chicago-illinois-1959-2005/" https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/robert-taylor-homes-chicago-illinois-1959-2005/

O’Beirne, J. (2019, January 16). It’s a beautiful day in Chatham. https://jasonobeirne.com/chatham-chicago/

Taylor, K.-Y. (2010, March 24). When Black homeowners fought back. Socialist Worker. https://socialistworker.org/2010/03/24/black-homeowners-fought-back

Wikipedia. (2022a, January 20). Robert Taylor Homes. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Taylor_Homes

Wikipedia. (2022b, February 14). North Lawndale, Chicago. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/North_Lawndale,_Chicago

Wikipedia. (2022c, February 26). Greater Grand Crossing, Chicago. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greater_Grand_Crossing,_Chicago

Wikipedia. (2022d, March 1). Chatham, Chicago. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chatham,_Chicago

Wikipedia. (2022e, March 16). Lake View, Chicago. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lake_View,_Chicago

Wikipedia. (2022f, March 18). Douglas, Chicago—Bronzeville. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Douglas,_Chicago#Bronzeville

Woodson, C. G. (2010). The mis-education of the Negro. Seven Treasures Publications

Gloria West

Gloria West

Gloria West’s life work is social service. She has over twenty years in the industry and more than twelve years in nonprofit management. Her experiences include advocacy, building partnerships, community outreach, and policy. She connects the most vulnerable groups to programs, services, and educational resources. In her efforts to support them she collaborates with local city and state government organizations, faith-based organizations, nonprofit organizations, and businesses.

She believes that families and individuals are resilient and grow stronger when they have access to holistic and equitable resources that help them overcome obstacles of oppression. Gloria recognizes that we cannot always prevent seen and unforeseen life events that derail people, but we can respond to those that are impacted faster. Her goal is to build community coalitions and strengthen existing collaborations, creating comprehensive wrap-around services for all.

Gloria earned her PhD from National Louis University in Community Psychology, her Master of Science Degree in Nonprofit Management from Spertus Institute, a Bachelor of Arts degree from Chicago State University, and a Child Development Certificate from the City Colleges of Chicago. She is a member of SCRA, CERA, and the National Society of Leadership and Success.

She understands that her approach to living a decolonized life is attributed to her mother unconsciously breaking her family’s cycle of generational trauma. Gloria also accredits her ability to preserve psychological freedom by continuing to push back on the systems of oppression through her Christian faith, self-love, family moral values, and lived experiences. These are tools that helped her identify psychological oppression. She believes we can liberate ourselves from oppressed lifestyles by understanding that our community dictates our resources, and our race dictates the equity within the resources. Her mission is to help people recognize oppression and free themselves from debilitating thinking, build self-efficacy, and obtain self-sufficiency and sustainability while living in our colonized world.

Add Comment

![]() Download the PDF version to access the complete article.

Download the PDF version to access the complete article.

Keywords: Community, racism, village