Roma are Europe’s largest ethnic minority and despite their national citizen status, 80% live in extreme poverty and have a much worse health status than their non-Roma counterparts. European institutions have identified the institutional discrimination targeted at Roma communities—antigypsyism—as the underlying cause of the violation of their rights (European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2018). Policies, practices and societal attitudes contribute to maintaining the status quo. From a community psychology perspective, we understand antigypsyism as institutional discrimination that needs to be addressed by creating processes with Roma communities that empower them to resist against this systemized oppression. Photovoice creates critical knowledge, increases individual skills to gain capacity to advocate and creates cohesion among oppressed groups to develop strategies for action (García-Ramírez et al., 2011). Thus, we propose that Photovoice can serve as a liberating process at the individual and community levels when utilized for advocacy. In this paper we present results of one aspect of RoAd4health (2016-2019), a project we carried out with Roma neighbors in Seville, Spain. The project aimed at developing advocacy processes in three at-risk, predominantly Roma neighborhoods to ensure the implementation and evaluation of Roma health policies through participatory action research (PAR). Here we focus on the potential of Photovoice to serve as a liberating process to resist antigypsyism. (Wang & Burris, 1997). In order to understand the individual and community impact of Photovoice for advocacy, we interviewed four of the Roma neighbor participants. Our analysis of the interviews resulted in two overarching themes from the citizen empowerment model (Kieffer, 1984): (1) From lack of consciousness to era of entry; (2) Achieving critical consciousness in the era of commitment; the second theme was divided into three subthemes, components of critical consciousness (Watts et al., 2011): (1) Critical reflection; (2) Political efficacy; and (3) Critical action. Overall, the Roma neighbors referred to the Photovoice as a method that instigated a conscientization process and helped gain commitment towards social justice actions, also reflected in actions following the Photovoice study. These results confirm that Photovoice as advocacy can contribute to individual empowerment and contribute to meaningful change towards community transformation to challenge antigypsyism.

Please see the PDF version for the full article, including figures and tables.

Recent reports consistently show that more than 80% of European Roma, the largest ethnic minority in Europe, live in poverty as a result of institutional discrimination (European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2018). European institutions have identified that the systemic discrimination targeted at Roma communities—antigypsyism—is the underlying cause of the violation of Roma rights and the failure of Roma policies. Many Roma communities in Europe live in extreme conditions that lack sewage systems, potable water, garbage collection, and many of the Roma settlements are located in contaminated industrial areas (Heidegger & Wiese, 2020; Harper et al., 2009). Roma people live at constant risk of being forcefully evicted and reallocated from their households due to gentrification (European Commission, 2016). These conditions are apparent across European countries, irrelevant of differences among national policies.

The oppression experienced by Roma people have resulted in lack of civic participation and opportunity to access resources for a healthy life despite European programs designed to better integrate Roma people (Council of Europe, 2018; Heidegger & Wiese, 2020). In 2005, National Roma Integration Strategies were created across EU member states. These policies involved non-governmental organizations and governmental actors in the development and implementation of action plans aimed at improving the living conditions of Roma. However, Roma participation was tokenized, which further silenced the most vulnerable Roma groups (McGarry & Agarin, 2019). For example, organizational networks developed provider-user relationships with the racial discrimination and marginalization lead to low self-esteem, feeling of powerlessness, and little participation in society (Crowley, Genova, & Sansonetti, 2013). In the next section, we present the effects of discrimination on Roma participation in Spain.

The Effects of Discrimination on Roma Participation in Spain

A recent report from the United Nations Rapporteur signaled that Roma people in Spain experience more unfair living conditions, poor health status, low employment rates, difficult access to good education, and lower life expectancy than the non-Roma (OHCHR, 2020). The report stated that the marginalized neighborhoods where Roma live were alarming, and it was noticeable that the “government appears to have abandoned the people living there” (OHCHR, 2020, p. 9). These conditions have been internalized and normalized by the Roma, reflecting the consequences of marginalization and its effects on the disempowerment of Roma living in these unjust contexts (Miranda et al., 2019).

These issues were exasperated and more visible during the initial lockdown measures of COVID-19. From March 2020 Roma people suffered additional discrimination related to governmental responses and guidelines that were not sensitive to existing Roma conditions. For example, sanitary measures did not consider families in overcrowded housing, homes with lack of running water and unstable electricity, state support did not cover those that survive on informal economic activity, and finally online schooling overlooked the digital gap of Roma families (FRA, 2020; Korunovska & Jovanovic, 2020). Driven by racist beliefs and reminiscent of discriminatory practices from the past, Roma people were blamed by the media and politicians for the spread of the virus. These measures led to an increase in Roma exclusion and hate speech against them (Matache & Bhabha, 2020). For example, back to school measures were developed without the voices of Roma communities and have caused distrust between the educational system and Roma families. Roma communities are blamed for devaluing education, which further justifies their living conditions. More than ever, antigypsyism has excluded Roma people from being active citizens in social, political, and economic spheres (Alliance Against Antigypsyism, 2019).

Liberating Methodologies

Community psychology offers a series of methodologies and values that can reverse the effects of antigypsyism by creating collaborative processes with Roma people that empower them to resist and challenge the oppressive narratives against them and build new ones. Through community-based participatory action research (CBPAR), communities have the opportunity to create their own knowledge, increase skills to gain the capacity to advocate, and create cohesion among oppressed groups to develop strategies for action (García-Ramírez et al., 2011). CBPAR linked to advocacy allows citizens to feel empowered to control the decisions that affect their lives and helps their voices to be heard. It also assists with recognizing their priorities and addresses their real needs (Balcazar et al, 2012). With policies that are not aligned with their realities, Roma people are left in abandonment, and they are collectively made helpless and marginalized, while dominant voices continue to prevail (Briones-Vozmediano et al., 2018). Through CBPAR, Roma people shift the concept of themselves individually as well as their community, which lead to recognition, equitable influence, and access to resources.

The objective of this paper is to highlight the transformation in personal and collective narratives of a group of Roma neighbors who were involved in a CBPAR project. This project, Road4health, was linked to local advocacy efforts to improve the health of local Roma communities in Seville, Spain through a Photovoice methodology for advocacy. The interviews analyzed in this paper were conducted with participants after the Photovoice project. We propose that Photovoice linked to community advocacy efforts can transform narratives in terms of how Roma perceive their role in community change.

From a community psychology perspective, we understand that individuals have an expansive capacity to lead in changes that affect their lives by uncovering the injustices against them when given the tools to do so. In this study we utilized a Photovoice methodology linked to community advocacy, which we understood as a process that promotes meaningful engagement of communities to address the concerns through their eyes and voices (Suarez-Balcazar, 2020). The methodology also explains social and political realities and develops critical consciousness (Seedat et al., 2015). Through liberating methodologies that assume participants as co-researchers and equal contributors to the research process, from data collection to analysis, Roma people had the opportunity to re-narrate their experiences with oppression caused by antigypsyism (Foster-Fishman et al., 2010; Miranda et al., 2020). Photovoice has been utilized in community-based participatory action research since Wang and Burris (1997) gave rural women a vehicle to shed light on their lives and build a narrative around their personal and collective experiences. Various authors working with “hard-to-reach” populations, such as people experiencing homelessness, migrants, those with low-income, women, or youth, have utilized Photovoice (e.g. Budig et al., 2018; Madrigal et al., 2014; Royce et al., 2006; Seedat et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2000). The Photovoice procedure entails: (1) researchers posing a framing question that probes reflection (i.e. what are the health concerns in your community?), (2) community members taking photographs that answer the framing questions, (3) community members share photographs and present their individual experiences (i.e. researchers utilizing questions from the SHOWeD methodology provided by Wang et al., 1997), (4) utilizing the photographs and narratives to undergo a collaborative thematic analysis of the photographs and narratives between researchers and community members (i.e. following Foster-Fishman et al, 2010 Youth ReACT methodology), and (5) utilizing this new-found theory to advocate for change across various settings (i.e. following the meaningful community advocacy model Miranda et al, 2020).

Authors that have critically reviewed Photovoice have suggested looking at the implications for empowerment of the methodology to understand its usefulness in the process within the larger contextual and political arena (Liebenberg, 2018). Catalani & Minkler (2010) reviewed literature that included the Photovoice methodology unveiling the lack of studies that evaluated the implications of Photovoice on individual narratives. Some years later Budig et al. (2018) found from their study that this methodology empowers participants increasing their knowledge and skills, participation and social networks, and improving their self-perception. In order to monitor and further understand the potential impact that Photovoice methodology has when utilized for advocacy purposes, we interviewed participants about the Road4health project which incorporated a Photovoice study for advocacy.

Based on Bruner's narrative construction model (1996), we conceptualize narratives as a way of constructing human reality and events over time, of meaning-making of processes and events. According to him, narratives are based on our own individualized experiences, how they relate to others and how they are influenced by time and culture. For Roma people, their narratives have been co-opted or tokenized. For example, the lack of Roma representation in political spaces at the local level—both in the City Council and in local neighborhood coalitions and grassroots movements—has silenced Roma living in the most marginalized areas. At the national level, there is a Roma State Council that does a widespread effort for Roma rights—for example, denouncing antigypsyism. In some cases this has duplicated power structures between organizational leaders and the everyday neighbors. Other leaders have adopted a feminist movement that has left behind the complicated narratives of Roma women and girls living in contexts with little resources and opportunities (Garcia-Ramirez et al, 2020.). In this sense, Roma are now recognized in political spheres, yet are not heard (Vernmeersh & Van Baar, 2018). Roma lives have been defined by the majority culture, and antigypsyist cultural explanations have been used to control and victim-blame Roma people. Therefore, we believe that liberating methodologies such as Photovoice can help to deconstruct this assumed reality. When linking Photovoice to advocacy, through a horizontal relationship with researchers, the participants can gain the capacity to respond to injustices, represent themselves and reconstruct their narratives based on their experiences.

Linking Citizenship Empowerment to Critical Consciousness

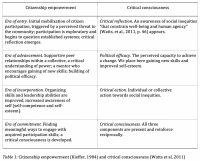

In order to resist oppressive narratives and situations, community psychology principles argue that a sociopolitical development process should occur (Baker, & Brookins, 2014), and a part of this process is developing the critical consciousness of individuals and groups. According to Watts et al. (2003), sociopolitical development involves context and personal experiences as mediating elements to awaken this consciousness. In our study we categorized the coded narratives into the three components of Watts’ et al. (2011) model of critical consciousness and used overarching themes of Kieffer’s (1984) citizenship empowerment model, as the two theories complement each other. Please see Table 1.

The Photovoice linked to advocacy, builds on the notion of critical consciousness, which consists of critical reflection, political efficacy and critical action (Watts et al., 2011). We argue that Watts’ model mirrors the Photovoice CBPAR methodology when linked to advocacy as presented by Miranda et al. (2020). The interviews carried out in this study were done after the Photovoice process and consist of the community members’ reflections regarding the changes they observed within themselves as a result of their participation. Utilizing Kieffer’s (1984) citizen empowerment model and Watts’ components of critical consciousness helped us to identify the stages of change within grassroots efforts as a result of the liberated narratives through Photovoice. CBPAR, when linked to community advocacy efforts over a long period of time can help individuals become and grow as leaders within their community.

Method

Background

The Photovoice study was part of a larger project Road4health, which was financed by the Open Society foundations (2016-2019) and took place in three marginalized neighborhoods with high Roma populations in Seville, Spain: Torreblanca, Poligono Sur and El Vacie. The aim of this project was to build advocacy capacity among Roma neighbors and a group of health care professionals to advocate for Roma health at the local level. A university-community partnership was developed by University researchers from the Coalition for the Study of Health, Power and Diversity (CESPYD), a Roma NGO, and three Roma communities. Roma neighbors utilized a Photovoice method for the purpose of advocacy actions that were implemented and targeted at various audiences, in the following steps: (a) prioritize social determinants of health in their communities, (b) take related photographs of their neighborhoods, (c) discuss and categorize photographs for thematic analysis, (d) develop a set of advocacy objectives based on their findings and identify allies (e) take short-term and long-term actions. The Photovoice sessions took place over the course of weekly sessions for two months, followed by advocacy actions. For more information on the Photovoice studies please see Miranda et al. (2019) & Miranda, Gutierrez-Martinez, Vizarraga-Trigueros & Albar-Marin (2020).

In order to understand the efficacy of this methodology in the Roma communities, we conducted interviews with some participants in the project. This paper focuses on the analyses of the interviews.

Participants in Interviews

Four Roma women, between the ages of 19 and 46. None of them had finished secondary schooling and each had at least one child. The women, from two predominantly Roma neighborhoods in Seville, Spain, Poligono Sur and Torreblanca, volunteered for the interviews.

Data Collection and Analysis

In order to understand the individual and community impact of Photovoice for advocacy, two researchers conducted semi-structured interviews with these four participants. The purpose of these interviews was to evaluate the Road4health project, from the Photovoice through the corresponding advocacy elements, and collectively reflect on the process. Examples of the interview questions were: (a) what have you learned through this project, (b) do you think you have the capacity to influence your community, (c) what was it like working with university researchers, (d) what was it like meeting with healthcare professionals, (e) what do you think you can keep doing to improve your community? Two interviews were carried out individually, while the other two participants answered in the same session, simultaneously. Interviews lasted between 30 minutes and 1 hour. All were recorded and then transcribed by two graduate students who didn’t take part in the interviewing process.

The interviews were analyzed utilizing an Atlas.ti software. A theoretically based thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) was carried out to identify the transformation in participants' narratives in terms of perceived citizen participation in their communities, according to the processes of citizen empowerment and building of critical consciousness in the participants as a result of their participation in the project. First, we searched for meaningful units in the narratives and used a free-coding procedure for the selected quotations. Then the ones that represented the three components of critical consciousness were divided into the previously selected subthemes “Critical reflection”, “Political efficacy” and “Critical action”, derived from the concept of critical consciousness (Watts et al., 2011). As major themes we used the first and the last stages of the citizen empowerment as a developmental process (Kieffer, 1984): “Before the project: From lack of consciousness to the era of entry” and “After the project: Achieving critical consciousness in the era of commitment” to better compare the transformation process. Please refer to Table 1 for definitions.

Results

Our results showed that as a consequence of Photovoice and advocacy actions, participants experienced an empowerment process and gained critical consciousness. In their narratives, the women expressed the growth from before to after project participation. We followed the stages from Kieffer’s model of citizen empowerment (1984) to describe the changes: participants started the project without critical consciousness, then passed through the development stages during every step of the Photovoice process and finally achieved the era of commitment. We divided this era of commitment into three subthemes, corresponding to Watts' (2011) three components of critical consciousness, as they are all present in this empowerment stage. The most representative quotes of each theme were selected to emphasize the development/changes which occurred during the project.

Before the project: From Lack of Consciousness to the Era of Entry

Before the project, the participants had no critical consciousness about the oppression and had normalized the living conditions in their communities.

Normalization:

They also didn’t have skills to speak in public and felt insecure about their capacity to advocate for their rights.

Lack of capacity:

Insecurity:

That’s why, at the beginning of the project the participants positioned themselves lower in society than the people outside of their community: researchers, students, and health professionals.

Feeling of inequality:

Their narratives about the time before the project reveal passivity and lack of reaction against the injustice.

Passivity:

The lack of support from public institutions such as social services, waste management and healthcare services provoked feelings of hopelessness and abandonment in the participants and their communities.

Hopelessness:

Precisely this and the negative attitude and blame from outside was a key factor that acted as a trigger to open their eyes and lead to the emergence of critical reflection and the era of entry.

Facing negative attitude:

Blamed:

After the project: Achieving Critical Consciousness in the Era of Commitment

Critical Reflection: Understanding Oppression

The narratives showed that all the participants increased their awareness through the Photovoice project, and realized the inequity in which they live.

Awareness through photos:

Awareness of inequity:

This provoked strong feelings such as anger and indignation, but also sadness because of the realized inequity.

Anger:

Sadness:

With the emergence of critical reflection they could overcome the internalized oppression and see themselves as equal to other people: researchers, health professionals, students, and citizens from better maintained neighborhoods.

Feeling of equality:

Political Efficacy: Perceived Capacity to Make a Change

The change from before to after the project wouldn’t be possible without the support from the researchers who had the role of mentors for the participants.

Mentorship:

This relationship contributed to participants’ personal development and self-esteem, but at the same time it was horizontal and without superiority and helped them gain strength.

Gaining self-esteem:

Gaining strength:

As the women interacted with the researchers, they began to compare themselves with them, seeing that they are no different. Participants highly valued the new skills to speak in public and express themselves in the professional sphere.

Gaining new skills:

After the meetings with health professionals from different institutions, held during the project, the participants felt stronger and independent.

Gaining independence:

Speaking in public served as an instrument for empowerment, improved self-perception and perceived capacity to change the oppressive system.

Gaining capacity:

Critical Action: Individual and Collective Reaction Against Inequity

With the critical reflection and political efficacy, participants became more decisive and empowered to change the situation. The project also helped them understand that they do not have to conform to the unjust conditions in which they live and that they have the resources for achieving a change advocating for their rights.

Nonconformity:

They started to set bigger goals and decided to influence the community, and to start to require more from them.

Bigger goals:

Decisiveness:

Requirements towards others:

During the empowerment process, the participants showed commitment to the actions they started with the desire to learn more and to continue their personal development.

Commitment:

They started to give ideas for action, understood the importance of unity within their community and expressed the readiness to initiate collective action.

Ideas for action:

Collective action:

Discussion

The objective of this study was to reflect on the process of community-based participatory action research (CBPAR) with a group of Roma neighbors who participated in the RoAd4Health project. We wanted to determine if the Photovoice methodology linked to advocacy can change personal and dominant cultural narratives and facilitate a liberation process. Our results confirm that the used methodology promoted personal development, helped participants gain critical awareness and sparked initiatives for individual and collective action. These results support findings from earlier community psychology studies (Balcazar et al., 2012; García-Ramírez et al., 2011; Paloma et al., 2009). Our study supports the power of critical consciousness to transform narratives of oppression and to empower people from minority groups (Chan & Mak, 2019; Freire, 1972).

Golden (2020) raised a series of concerns regarding the empowerment rhetoric around Photovoice. In this article we interpreted empowerment as a developmental process, according to Kieffer’s model (1984). The era of entry which started with the process of taking photographs of the poor living conditions, corresponds to the first component of critical consciousness when individuals begin to identify the relations of power and desire to participate in political decisions is stimulated. To achieve this first era of entry, a thread for the community is necessary (Kieffer, 1984) and the negative attitude of health professionals expressed in the meetings with them acted as one. Thus, our findings confirmed that dominant narratives about Roma people amongst health professionals are the most present (Briones-Vozmediano et al., 2018). The participants in our project reflected that this negative attitude helped them gain awareness and provoked group-based anger which influenced the critical action (Chan & Mac, 2019; Watts et al., 2011).

An important outcome from the participation of the Roma women in the project was their commitment to empower and involve the whole community in the advocacy actions, like the adolescents from a youth advocacy group (Nicholas et al., 2019). Following lockdown measures and the COVID-19 crisis, the same women involved in the Road4health project have continued to advocate for their rights and formalized into an advocacy group in two neighborhoods. These commitments and increased agency are characteristic for the era of commitment from the empowerment process (Kieffer, 1984). As reflected across the theories of empowerment, this process takes years of cultivating the relationship between researchers and the community. The horizontal relationship between researchers and participants built during the project is a key element of impactful Photovoice. As stated by Wang & Burris (1994), empowerment needs access to knowledge, decisions, networks and resources. Without access to these Photovoice may have no social or political impact, therefore, the key role of researchers in integrating an advocacy process with Photovoice helps to promote critical knowledge, the expansion of networks and allies, identification and access of resources and builds capacity for decision-making (Miranda et al, 2020).

It is clear from the analyzed narratives that this relationship was beneficial for the participants as they felt supported and understood. Such empowering results including personal development, better self-perception, and development of new social networks with peers to confront challenges affirm results from other studies (Aamboe, Escobar-Ballesta, García-Ramírez, 2017; Balcazar et al., 2012). Democratizing the co-creation of knowledge reconnects marginalized groups to the scientific community in order to influence change. The relationships established between the research partners and community members challenged the traditional roles adopted in the research process. Participants were co-researchers who collected data, made sense of the data and were part of the decision-making processing. Together both university researchers and community members spent time in their respective neighborhoods through both formal and informal encounters, collaborated together in the university settings (i.e. classrooms and conferences) and established a relationship that was founded on trust and mutual recognition.

The Photovoice methodology creates a safe environment for critical reflection and further development of critical consciousness (Carlson et al., 2006). This study confirms the importance of critical consciousness for overcoming internalized oppression and initiating collective action (Chan & Mac, 2019). Without the awareness stage, action does not take place. As reflected in other studies that utilize Photovoice, we confirmed that building capacity for advocacy using Photovoice empower and lead to personal development (Budig et al, 2018), improved self-esteem, self-confidence, critical thinking and perceived control (Teti et al., 2013), and enhances mutual learning and cohesion in the community (Duffy, 2011; Kovacic et al, 2014).

Our study presents a series of limitations. First, this is a small group that is not representative of all Roma communities across Europe. Nevertheless, the deep analyses of the interviews did provide us with interesting results that seem to support and add on to previous research with CBPAR. For example, that processes that involve silenced populations have the capacity to build critical consciousness (Chan & Mak, 2019) and new sociopolitical skills (Madrigal et al., 2014), that communities have the capacity to identify issues that affect them and represent themselves for change (Suarez-Balcazar, 2020). It is also hard to evaluate the development as reflected in Kieffer’s model because these phases take years to develop. We would need to conduct similar interviews at a later time to see whether the results still hold.

More research with ethnic minority communities, especially ethnic minority women, girls and sexual minorities should be included in CBPAR to contribute to challenging the hegemonic narrative that is sometimes attached to ethnic communities as a whole which then attribute poor health to cultural behaviors. Photovoice and other CBPAR methodologies identify and deconstruct power structures and should go a step further to understand the different forms of marginalization that ethnic minority women experience during the research process by incorporating reflexivity (Palencia et al., 2014). This should include aspects such as reviewing positions of power during the research process, exchanging experiences in order to challenge the status quo, triangulating outcomes with community members and consistent knowledge transfer (Abrams et al, 2020). Future researchers should ask the following questions: How much is the community really a part of the research process? Do the evidence we find at the local level triangulate with findings from other top-down approaches, is there common ground we can use to strengthen the voice of ethnic communities? How can we use Photovoice or other CBPAR methodologies to promote resilient communities during pandemic or other global crisis? The role of community psychologist includes the self-examination process in order to ensure a reciprocal conscientization that is truly a liberating methodology.

References

Aamboe, A., Escobar-Ballesta, M., & García-Ramírez, M. (2017). Liberation narratives against gender-based violence in a community of Pakistani women in Norway. Fokus Pa Familien, 3, 227–245.

Abrams, J., Tabaac, A., Jung, S., & Else-Quest, N. (2020). Considerations for employing intersectionality in qualitative health research. Social Science & Medicine, 113138.

Alliance Against Antigypsyism. (2016). Antigypsyism–a reference paper. Retrieved January 2020.

Baker, A. M., & Brookins, C. C. (2014). Towards the development of a measure of sociopolitical consciousness: Listening of the voices of Salvadorian youth. Journal of Community Psychology, 42 (8), 1015-1032.

Balcázar, F., Suárez-Balcázar, Y., Adames, S. B., Keys, C. B., García-Ramírez, M., & Paloma, V. (2012). A case study of liberation among latino immigrant families who have children with disabilities. American Journal of Community Psychology, 49, 283-293.

Briones-Vozmediano, E., La Parra-Casado, D., & Vives-Cases, C. (2018). Health providers narratives on intimate partner violence against Roma women in Spain. American Journal of Community Psychology, 61, 411-420.

Brown, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3:2, 77-101.

Bruner, J. (1996). A narrative model of self-construction. Psyke & Logos, 17 (1), 154-170.

Budig, K., Diez, J., Conde, P., Sastre, M., Hernán, M., & Franco, M. (2018). Photovoice and empowerment: Evaluating the transformative potential of a participatory action research project. BMC Public Health, 18 (1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5335-7

Carlson, E. D., Engbretson, J., & Chamberlain, R. M. (2006). Photovoice as a social process of critical consciousness. Qualitative Health Research, 16 (6), 836–852.

Catalani, C., & Minkler, M. (2010). Photovoice: A review of the literature in health and public health. Health education & behavior, 37(3), 424-451.

Chan, R. C., & Mak, W. W. (2020). Liberating and empowering effects of critical reflection on collective action in LGBT and cisgender heterosexual individuals. American Journal of Community Psychology, 65(1-2), 63-77.

Council of Europe (2018). Recommendation of the Committee of Ministers to members states on the participation of citizens in local public life. https://rm.coe.int/09000016807954c3

Crondahl, K., & Karlsson, L.E. (2015). Roma empowerment and social inclusion through work-integrated learning. SAGE Open, 1-10.

Crowley, N., Genova, A., & Sansonetti, S. (2013). Empowerment of Roma women within the European framework of national Roma inclusion strategies. Brussels, European Union [Online], available from http://www. europarl. europa. eu/RegData/etudes/etudes/join/2013/493019/IPOL-FEMM_ET (2013) 493019_EN. Pdf.

Duffy, L. R. (2011). ‘‘Step by step we are stronger’’: Women’s empowerment through Photovoice. Journal of Community Health Nursing, 28, 105-116.

European Commission (2016). Assessing the implementation of the EU Framework for National Roma Integration Strategies and the Council Recommendation on Effective Roma integration measures in the Member States 2016. European Commission, Justice and Consumers.

European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (2018). A persisting concern: Anti-Gypsyism as a barrier to Roma inclusion. European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. http://fra.europa.eu/en/publication/2018/roma-inclusion

Foster-Fishman, P. G., Law, K. M., Lichty, L. F., & Aoun, C. (2010). Youth ReACT for social change: A method for youth participatory action research. American Journal of Community Psychology, 46(1–2), 67–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-010-9316-y

Freire, P. (1972). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. 1968. Trans. Myra Bergman Ramos. New York: Herder.

García-Ramírez, M., de la Mata, M. L., Paloma, V., & Hernández-Plaza, S. (2011). A liberation psychology approach to acculturative integration of migrant populations. American Journal of Community Psychology, 47(1–2), 86–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-010-9372-3

Garcia-Ramirez, M., Soto-Ponce, B., Albar-Marín, M. J., Parra-Casado, D. L., Popova, D., & Tomsa, R. (2020). RoMoMatteR: Empowering Roma Girls’ Mattering through Reproductive Justice. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(22), 8498.

Golden, T. (2020). Reframing photovoice: Building on the method to develop more equitable and responsive research practices. Qualitative health research, 30(6), 960-972.

Harper, K., Steger, T. & Filcak, R. (2009). Environmental Justice and Roma Communities in Central and Eastern Europe. Environmental Policy and Governance, 19, 251-268.

Heidegger, P. & Wiese, K. (2020). Pushed to the wastelands: Environmental racism against Roma communities in Central and Eastern Europe. Brussels: European Environmental Bureau.

Kieffer, Ch. H. (1984). Citizen Empowerment: A Developmental Perspective. The Haworth Press.

Kovacic, M. B., Stigler, S., Smith, A., Kidd, A., & Vaughn, L. M. (2014). Beginning a partnership with PhotoVoice to explore environmental health and health inequities in minority communities. International journal of environmental research and public health, 11(11), 11132-11151.

Labbé, D., Mahmood, A., Routhier, F., Prescott, M., Lacroix, É., Miller, W. C., & Mortenson, W. B. (2021). Using photovoice to increase social inclusion of people with disabilities: Reflections on the benefits and challenges. Journal of Community Psychology, 49(1), 44-57.

Liebenberg, L. (2018). Thinking critically about Photovoice: Achieving empowerment and social change. International Journal of qualitative Methods, 17, 1-9.

Madrigal, D., Salvatore, A., Casillas, G., Casillas, C., Vera, I., Eskenazi, B., & Minkler, M. (2014). Health in my community: Conducting and evaluating photovoice as a tool to promote environmental health and leadership among Latino/a youth. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action, 8 (3), 267-268. https://dx.doi.org/10.1353%2Fcpr.2014.0034

Matache, M. & Bhabha, J. (2020). Anti-Roma Racism is Spiraling during COVID-19 Pandemic. Health and human rights journal, 22 (1), 379-382.

McGarry, A., & Agarin, T. (2014). Unpacking the Roma participation puzzle: Presence, voice and influence. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 40(12), 1972-1990.

Miranda, D. E., Garcia-Ramirez, M., & Albar-Marin, M.J. (2020). Building meaningful community advocacy for ethnic-based health equity: the Road4health experience. American Journal of Community Psychology.

Miranda, D. E., Gutiérrez-Martínez, A., & Albar-Marín, M. J. (2020). Training for Roma health advocacy: a case study of Torreblanca, Seville. Gaceta Sanitaria. 10.1016/j.gaceta.2020.09.002

Miranda, D. E., Garcia-Ramirez, M., Balcazar, F. E., & Suarez-Balcazar, Y. (2019). A community-based participatory action research for Roma health justice in a deprived district in Spain. International journal of environmental research and public health, 16(19), 3722.

Morgan, M. Y., Vardell, R., Lower, J. K., Kintner-Duffy, V. L., Ibarra, L. C., & Cecil-Dyrkacz, J. E. (2010). Empowering women through Photovoice: Women of La Caprio, Costa Rica. Journal of Ethnographic & Qualitative Research, 5, 31-44.

Nicholas, C., Eastman-Mueller, H., & Barbich, N. (2019). Empowering change agents: Youth organizing groups as sites for sociopolitical development. American Journal of Community Psychology, 63, 46-60.

Palencia, L, Malmusi, D., & Borrell, C. (2014). Incorporating intersectionality in evaluation of policy impacts on health equity. A quick guide. Agència de Salut Públicade Barcelona, CIBERESP; 2014. Available from: http://www.sophie-project.eu/pdf/Guide intersectionality SOPHIE.pdf

Paloma, V., García-Ramírez, M., de la Mata, M., & Association, A. M. A. L. (2010). Acculturative integration, self and citizenship construction: The experience of Amal-Andaluza, a grassroots organization of Moroccan women in Andalusia. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 34(2), 101-113.

Royce, S. L., Parra-Medina, D., & Messias, D. H. (2006). Using Photovoice to examine and initiate youth empowerment in community-based programs: A picture of process and lessons learned. Californian Journal of Health Promotion, 4 (3), 80-91. https://doi.org/10.32398/cjhp.v4i3.1960

Seedat, M., Suffla, S., & Bawa, U. (2015). Photovoice as emancipatory praxis: A visual methodology toward critical consciousness and social action. Methodologies in Peace Psychology, 309-324.

Suarez?Balcazar, Y. (2020). Meaningful engagement in research: community residents as co?creators of knowledge. American Journal of Community Psychology, 0, 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12414

Teti, M., Pichon, L., Kabel, A., Farnan, R., & Binson, D. (2013). Taking pictures to take control: Photovoice as a tool to facilitate empowerment among poor and racial/ethnic minority women with HIV. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 24 (6), 539-553.

United Nations Human Rights Office of the Higher Commissioner (ONHCR). (2020). Statement by Professor Philip Alston, United Nations Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights, on his visit to Spain, 27 January – 7 February 2020. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=25524&LangID=E Retrieved on July 16, 2020.

Vermeersch, P., & Van Baar, H. (2017). The limits of operational representations. Intersections, 3(4). https://doi.org/10.17356/ieejsp.v3i4.412

Wang, C., & Burris, M. A. (1997). Photovoice: Concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Education & Behavior, 24(3), 369–387. https://doi.org/10.1177/109019819702400309

Wang, C. C., Cash, J. L., & Powers, L. S. (2000). Who knows the Streets as well as the homeless? Promoting personal and community action through Photovoice. Health Promotion Practice, 1 (1), 81-89.

Watts, R. J., Diemer, M. A., & Voight, A. M. (2011). Critical consciousness: Current status and future directions New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2011, 43–57.

Watts, R. J., Williams, N. C., & Jagers, R. J. (2003). Sociopolitical development. American Journal of Community Psychology, 31, 1/2.

Table 1: Citizenship empowerment (Kieffer, 1984) and critical consciousness (Watts et al, 2011) |

Daniela E. Miranda, Lilyana Zhelyazkova, and Jana Sladkova

Daniela E. Miranda, Lilyana Zhelyazkova, and Jana Sladkova

Daniela E. Miranda candidate in the Social Psychology Department at the Universidad de Sevilla (Spain) and researcher at the Center for Community Action-Research. She is passionate about amplifying the voices of historically marginalized women and girls across community, academic and political settings. Expertise includes civic engagement, community-based participatory action research, intersectional health equity, and reproductive justice.

Lilyana Zhelyazkova holds a Master of Psychology of Social and Community Intervention from the University of Seville and a Bachelor of Psychology from the Sofia University. She is currently working for achieving social inclusion and health justice for Roma people in Bulgaria. Her professional interests are related to participatory action research approaches and their influence on the process of sociopolitical development of marginalized communities.

Jana Sládková is an Associate Professor of Psychology at the University of Massachusetts Lowell. She is a co-coordinator of the M.A. in Community Social Psychology and a coordinator of the B.A. concentration in Community Psychology. Jana’s main research interests are in (undocumented) migration issues, diversity and inclusion, and qualitative research inquiry.

Add Comment

![]() Download the PDF version to access the complete article.

Download the PDF version to access the complete article.

Keywords: Roma, health disparities, Photovoice, narrative, empowerment, critical consciousness, sociopolitical development, community-based participatory action research, advocacy