Researchers have argued for the positive impact education legislation can have as a macrosystem-level intervention on the implementation of microsystem- and mesosystem-level interventions (e.g., Gay-Straight Alliances) empirically documented to support sexual and gender minority students. This paper presents the findings of a qualitative Community-Based Research study that explored the perspectives of advocates for LGBT students from Waterloo Region, Ontario, Canada, on the impact of Bill 13; a bill purportedly proposed to address the needs of minority youth in publicly-funded schools. This paper emphasizes the value of legislation that is able to both explicitly mandate the implementation of LGBT-affirming initiatives empirically recognized to promote student mental health, and provide flexibility for advocates to develop new initiatives that will meet the specific needs of their minority students.

Download the PDF version to access the complete article, including Tables and Figures.

Perhaps one of the most prominent theoretical frameworks considered central to Community Psychology discourse, research, and practice (Jason et al., 2016; Nelson & Prilleltensky, 2010), Urie Bronfenbrenner’s (1977) ecological systems theory (to see Table 1, download the PDF version to access the complete article, including Tables and Figures) has been utilized and adopted over the years to underscore the need to recognize interdependent, multi-level systems of influence and intervention that impact the development and wellbeing of children and youth, particularly those most vulnerable to mental health challenges in schools (Burns, Warmbold-Brann, & Zaslofsky, 2015; Hornby, 2016; Lee, 2011). Because of its broad applicability, the ecological systems theory has been readily applied to various research contexts involving developing youth.

Community psychologists have made considerable use of the ecological metaphor Bronfenbrenner described in their own research and practice (Trickett, Kelly, & Todd, 1972). Because of its ability to contextualize issues and problems faced by disadvantaged people over time and across multiple nested levels of analysis (Nelson & Prilleltensky, 2010), the ecological systems theory has had a wide range of practical applications that have proved valuable to many Community Psychology research areas and focuses. As a theory that places value in holism over reductionism, the relevance of the ecological systems theory to the research focus and context of the study described and discussed in this article is that it underscores the importance of the interconnectedness and interdependence of social phenomenon and factors found in the smaller systems (e.g., individual-level: characteristics of the individual LGBT youth, microsystem-level: school teacher support for students) with those found in the larger systems (e.g. mesosystem-level: LGBT-affirming collaboration between school faculty and community service providers, macrosystem-level: societal homophobia and LGBT-positive legislation). Moreover, the ecological systems theory recognizes the significant impacts that the interconnectedness and interdependence of these nested structures could have on vulnerable individuals within an open ecological environment where social phenomena and factors from the different system-levels are free to dynamically interact and considerably influence one another, and more importantly, developing youth (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Nelson & Prilleltensky, 2010; Trickett et al., 1972).

For instance, in empirical investigations, much attention has been given to the positive effects of family, peer, and school microsystems on the mental health and wellbeing of the individual sexual and gender minority youth (Kosciw, Greytak, Giga, Villenas, & Danischewski, 2016; Kosciw, Greytak, Palmer, & Boesen, 2014; Poteat, Rivers, & Vecho, 2015). Several research studies have focused on the perspectives and important roles of parents, fellow students (i.e., both LGBT and non-LGBT youth), teachers, counsellors, administrators, and community advocates in the direct provision of personal and social support, as well as on the creation of Gay-Straight Alliances (GSAs), which have been empirically documented to create positive school environments and safe spaces for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) youth in schools (Goldstein & Davis, 2010; Hatzenbuehler, 2011; Kosciw, Greytak, Diaz, & Bartkiewicz, 2010; Valenti & Campbell, 2009).

In this same context, mesosystem-level interactions (i.e., those that do not involve direct interaction with sexual and gender minority youth) of entities within and between these microsystem settings have also been the focus of studies on interventions promoting the mental health of LGBT students in recent decades. Research has shown that the perspectives, collective advocacy, and collaborations and partnerships between ally (i.e., non-LGBT) student leaders, teachers, staff, counsellors, principals and vice-principals, and school board trustees have led to the successful implementation of LGBT-affirming initiatives such as the incorporation of age-appropriate, LGBT-positive material in school curricula and lesson plans (Bellini, 2012; Bittner, 2012; Fisher et al., 2008; Ryan, Patraw, & Bednar, 2013); the practice of LGBT-inclusive in-service professional development training of school employees (Bellini, 2012; Case & Meier, 2014; Fisher et al., 2008; Greytak, Kosciw, & Boesen, 2013; Mayo, 2013); and the creation of board-wide policies that explicitly recognize and address critical issues such as bullying, victimization, and harassment related to students’ sexual orientation and gender identity (Fisher et al., 2008; Goldstein, Collins, & Halder, 2007; Kosciw, Palmer, Kull, & Greytak, 2013) – all of which have been documented by research to support individual-level LGBT youth mental health and wellbeing.

Unfortunately, although a number of articles have been published in academic literature that highlight the value of macrosystem-level interventions such as legislation and public policies in the promotion of microsystem- and mesosystem-level interventions empirically documented to support the mental health of sexual and gender minority students (Anderson, 2014; Rayside, 2014; Winton, 2012), there has not been a great deal of studies conducted that examine the perspectives of key stakeholders on the impact of legislation on such initiatives dedicated to foster the wellbeing of LGBT youth (Bellini, 2012; Kitchen & Bellini, 2013). This may be because of the controversial and political natures of the issues that are involved with examining stakeholder perspectives on provincial legislation; or perhaps because there are not enough research agendas that have been funded and supported in the recent past to highlight the importance of exploring and promoting the perspectives of stakeholders from relevant communities, a key component in Community Psychology research and practice (Nelson & Prilleltensky, 2010).

The aim of this paper is to present, discuss, and analyze the perspectives of relevant stakeholders from Waterloo Region, Ontario, Canada, on the potential impacts of a proposed provincial legislation, Bill 13, on advocacy, LGBT-affirming initiatives, and policies in publicly-funded schools that are dedicated to support the mental health of sexual and gender minority youth, based on the findings of the community-engaged qualitative study that we conducted in 2012, around the seven months before, during, and after Bill13 was legislated, passed, and then given royal assent in June of that year (Ontario Legislative Assembly [OLA], 2012).

Bill 13 was a piece of provincial legislation that was proposed by then Ontario Liberal Party leader and Premier Dalton McGuinty in 2011. It later came to be more popularly recognized as the Accepting Schools Act. Among many other things, Bill 13 was poised to be the controversial legal statute that would explicitly mandate all publicly-funded schools in Ontario, including all publicly-funded Catholic schools, to accept and support the establishment of GSAs upon the request of any of its students (Lewis, 2011). Bill 13 was purportedly proposed by the Ontario Liberal Party to impact and help support the wellbeing of all students in publicly-funded schools; especially those who needed more positive spaces to thrive. Specifically, this paper will present, discuss, and analyze the perspectives of students, teachers, staff, administrators, board trustees and superintendents, and community-based service providers from and collaborating with the Waterloo Region District School Board (WRDSB) and the Waterloo Catholic District School Board (WCDSB), who were actively working towards the promotion of LGBT student mental health and wellbeing in their schools at the time of our study.

Method

Partnerships

The participants included in our qualitative study were part of a larger study examining the success of GSAs and other LGBT-affirming initiatives in supporting sexual and gender minority students in Waterloo Region, Ontario, Canada. The Equity, Sexual Health, and HIV (ESH-HIV) Research Group of the Centre for Community Research, Learning, and Action at Wilfrid Laurier University undertook the larger study, in partnership with the OK2BME Program of KW Counselling Services of Waterloo Region. OK2BME is a program that offers counselling and support groups for LGBT youth, as well as education and training to service providers, school-based stakeholders, and the broader community. Over the years, the ESH-HIV Research Group, the OK2BME Program, and advocates from both district school boards of Waterloo Region have collaboratively worked together as community partners to identify and address LGBT youth concerns and issues in their region’s schools. It was because of these strong connections and collaboration that we were able to recruit and involve many participants for our study. The Wilfrid Laurier University Research Ethics Board (REB) reviewed and approved the purpose and conduct of our study. We used an REB-approved, interview guide to maintain a degree of structure during the study interviews (Appendix A).

Participants

Twenty-six stakeholders from Waterloo Region were interviewed within a seven-month duration (i.e., from March to September 2012) to explore and examine their perspectives on the potential impact of Bill 13, the Accepting Schools Act, on the advocacy, policies, and initiatives of publicly-funded schools dedicated to support the mental health and wellbeing of LGBT students. Each of the 26 stakeholders were interviewed only once at some point during the seven-month period of data collection, either before, during, or after Bill 13 was incidentally legislated, passed, and given royal assent in June 2012 (OLA, 2012). The different groups of stakeholders were all recruited during the same period of time, and each stakeholder was scheduled for interview based on their availability, and venue and time preferences, during the seven-month period.

The interviewees were recruited through a variety of strategies, initially using purposive sampling (Palys, 2008), and later, through snowball sampling (Morgan, 2008). Students were recruited in 2012 at the Waterloo Region GSA conference, an annual event co-sponsored by the OK2BME Program and the WRDSB, which brought together youth from across the region to network and discuss issues relevant to GSAs, as well as participate in workshops facilitated by LGBT community members. The recruitment was accomplished by posting REB-approved advertisement flyers at the premises of KW Counselling and the GSA conference location, and by making two public announcements on the day of the conference. Students who attended the conference were selected for recruitment because of their past or current membership in local GSAs. An additional recruitment flyer through the OK2BME Program’s e-mail network listserv was circulated, and an advertisement was placed using the same flyer on their website. Teachers, school staff, and board representatives at the GSA conference were also recruited by invitation through the personal and professional networks of the research team using REB-approved recruitment emails.

Students, teachers, school staff, administrators, and representatives from the two district school boards who were in unique positions to provide information and personal perspectives relevant to the objectives of the study were purposely recruited based on their roles, job descriptions, individual commitment, collaborative involvement, histories, and own lived experiences studying, and working in or with the Waterloo Region school systems, particularly in relation to advocacy for LGBT student mental health and wellbeing. Individuals from the two school boards were recruited during the GSA conference because many of them stood out as highly informed and actively engaged participants of the conference. They were outspoken and confident about their advocacy for LGBT youth issues in schools, and their passion for their advocacy was apparent during the conference, making them excellent candidates for the interviews of the study. Subsequently, some participants were recruited from the referrals of initial interviewees who suggested names of other key stakeholders in the school settings who would be able to share valuable perspectives on the research focus of the study.

At the time of the study analysis, 11 students from eight high schools, six teacher GSA sponsors from five high schools, seven representatives at the administration level of the two school boards, and two key informant service providers who provide LGBT counselling, education, and outreach support to the community (to see Table 2, download the PDF version to access the complete article, including Tables and Figures) had participated in the study’s confidential, digitally audio-recorded, semi-structured, open-ended interviews. Among the 11 students (to see Table 3, download the PDF version to access the complete article, including Tables and Figures), only one identified as transgender. None of the students identified as heterosexual; four identified as bisexual; and seven identified as gay/lesbian. There were five students who identified as male and six who identified as female. The students’ ethno-racial backgrounds were mostly white, with six students who identified as White-Canadians, two who identified as White-South Americans, and one who identified as White-European. Only two students identified as non-white, one who identified as Asian, and another who identified as someone of mixed Aboriginal-European descent. Eight of the students were from schools affiliated with the WRDSB and three were from a school affiliated with the WCDSB. Based on their cities of origin, seven students were from schools located in Kitchener, three students were from schools in Waterloo, and one student was from a school in Cambridge. Pseudonyms were assigned to each student from the beginning of the study to protect their privacy and confidentiality.

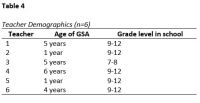

Among the six teacher GSA sponsors (to see Table 4, download the PDF version to access the complete article, including Tables and Figures), there was only one who confidentially identified as gay. Four of the teachers were from four different schools affiliated with the WRDSB and the other two were from a school affiliated with the WCDSB. None of the seven representatives at the administration level of the two school boards identified as a sexual or gender minority. From the seven board representatives, four were from the public school board, and three were from the Catholic one. Out of the seven board representatives, three were trustees, one was a superintendent, two were staff members who worked closely with school GSAs, and one was a school administrator. Each of the seven representatives at the administration level of the two school boards were in privileged positions of influence with regards to advocating for LGBT youth mental health and wellbeing. Most of them had already spent years advocating for LGBT students in their own capacities as school administrator, staff member working on equity and inclusion board initiatives, superintendent, or board trustee. This was also true for the two community-based service providers who had been in their positions for years. They have witnessed the positive changes brought about by their own advocacy for LGBT students, as well as the advocacy of other key stakeholders in Waterloo Region.

Procedures

Participants were interviewed either at the Wilfrid Laurier University campus or at a community location. The digitally audio-recorded, confidential interviews were between one to two hours in length. All participants provided written consent to participate in the study prior to their interview. Youth received a $25 honorarium following their participation. The youth each completed a Demographics Sheet detailing their age, sexual orientation, gender identity, and the number of years they had been with their GSA, as well as the city where their high school was located, and their ethno-racial background. Using another Demographics Sheet, teachers were asked about the grade level they taught in school and the age of the GSAs in their schools. However, information about the teachers’ ethno-racial background was not requested. Since there were a lot less teachers and administration-level representatives and service providers from the community who could have participated in the study, demographic information, particularly ethno-racial background, was not requested from them to protect their privacy and confidentiality.

The semi-structured interviews with the students focused on what their general impressions were of Bill 13, what they believed were the strengths and weaknesses of the bill and the benefits or challenges that would result from its legislation, and what other specific comments they had regarding the bill. The teacher GSA sponsors, representatives at the administration level of the two school boards, and the service providers were asked similar questions about their own perspectives on Bill 13.

Materials and Analysis

A modified version of the grounded theory approach to qualitative data analysis (Charmaz, 2008; Corbin & Strauss, 2008) was used in this study. The grounded theory method allows theory to emerge inductively from data rather than starting from a hypotheses and then deductively establishing findings. Instead of applying a theoretical framework to data, theory emerges from the data. Our research team modified this approach by establishing a categorical coding framework prior to inductive coding, which allowed analysis to focus on our areas of interest. We transcribed the recorded interviews verbatim without the use of transcription software, and then coded the transcribed interviews using NVivo 10. After reviewing the initial transcripts, our categorical coding framework was modified accordingly based on the research objectives, interview guide questions, our interviewer’s experiences, and the transcript data. Several categories were developed for the framework during this initial process.

In the second stage of coding, two members of our research team separately coded interviews with one youth, one teacher, one board representative, and one service provider to ensure intercoder reliability. Codes were developed inductively, through the use of open coding – using the coding framework as a guide for sorting the data (Corbin & Strauss, 2008). Next, our research team gathered together to reach consensus regarding any codes where disagreement existed. At the same time, members of our research team began to make connections among codes and discussed potential theories. Once consensus on the open codes was achieved from the interviews, the first author coded the remaining transcripts using the established coding framework.

During the final stage of coding, emerging themes, patterns, and relationships within and between participants’ responses were identified by the research team. The process of data triangulation (Denzin, 1989) between service provider, board representative, teacher, and student responses was used to enhance the credibility of the data. Themes were also appraised and altered iteratively and reflexively as a team (Watt, 2007), so that alternate explanations could be explored and discussed. It was kept in mind that researchers and participants in the study affected each other mutually and continually during the research process.

Results

According to the information shared by the participants, all 16 schools affiliated with the Waterloo Region District School Board (WRDSB) already had actively running GSAs; professional development in-service trainings on LGBT topics; close collaborative connections with the OK2BME Program and their board’s Equity and Inclusion Office; and policies, administrative procedures, and guidelines from their board that explicitly included sexual orientation as one of the bases for bias-based harassment and offenses related to discrimination. Additionally, several of the WRDSB schools that the respondents belonged to also had LGBT-positive events and campaigns every year; inclusion of LGBT topics in their curriculum; and available counselling specific for LGBT concerns. At least two of the schools affiliated with the Waterloo Catholic District School Board (WCDSB) were not far behind with similar initiatives and supports for their own LGBT students at that time. It was apparent from the interviews that the perspectives of the participants on advocacy for LGBT issues were going to be based on their lived and work experiences as key stakeholders who actively engaged and challenged their school systems in order to successfully establish and promote much needed changes. Their perspectives on Bill 13 were not just going to be opinions based on information that they had read or heard, but views that they developed from years of experiencing marginalization and/or advocating for LGBT youth’s needs and rights.

“It’s about time!” The first comments of the participants on Bill 13 could only be described as an overwhelmingly positive response. Although there were elements of discernible initial concern in some, most were full of anticipation and hope with what the legislation of Bill 13 could bring. Since the respondents were from a pool of LGBT youth and advocates who had been working on getting LGBT-positive initiatives established in their schools for years, it was not surprising that only one student among all the participants had not known about Bill 13 prior to joining the study. Most of the students were very enthusiastic with the thought of having a law that would set up supports and protections for LGBT youth in schools, and some teachers expressed that they thought it was about time something like Bill 13 was proposed. Sara was quite proud of the fact that Ontario was the first province to propose such a bill, “Ontario is one of the more powerful and influential provinces. I’m sure it will lead the way when it comes to this kind of legislation and then other provinces will eventually follow.” One of the teachers got emotional when she shared her initial reaction to hearing about Bill 13:

If we want to see consistent change at a ground level, it has to be legislated by the government. That means it has to have the legislative chops to be able to act and say, “You’re doing this because it’s the law”. It’s so that people can then say, “We’re doing this because it’s people’s civil rights. In Ontario, we believe that people have those rights and these are how they are encompassed.” When someone like the Premier says, “I don’t really care what your religious beliefs say, when there is something we must do to save our children’s lives, we do it.” That sends a huge message to the public.

Although she felt optimistic about the bill’s impending legislation, another teacher still had a little skepticism about what a law can actually accomplish:

“I think it’s amazing and it’s about time right? I also think that we’ve had anti-racist stuff for a long time, and very often, I don’t see that leading to any change at the school level. If the bill leads to change at the school level, then that will be even better. I think it could be useful for us because for us doing the work in the schools, we know we’re going to be supported.”

One of the service providers shared this skepticism saying that it will take a lot of time after legislation for change to happen, but also commented that she was in support of the bill, “There’s a real need for it, and we know it.” Two of the trustees had positive feedback. One of them remarked, “It’s a good piece of legislation. People should not be afraid of possible pushback. There’s always going to be some gripe for every new law.”

Reputation earned. As the discussion on Bill 13 went further in the interviews, it became more apparent that the bill had already earned a reputation for being a statute that was proposed specifically to force publicly-funded school boards in Ontario to allow the formation of GSAs in their schools, if there were students who requested for them. Nearly half of the participants had very little idea about the rest of the contents of Bill 13 and were surprised to hear that it had more amendments to the Education Act (Ontario Legislative Assembly [OLA], 1990) that required specific tasks from the Education Minister, the school boards, and the school principals of Ontario, which addressed more needs of LGBT students. More so, for those respondents who thought that the bill was mostly about coercing Ontario publicly-funded schools to support GSAs, and even for some respondents who did know that there was more to the bill, Bill 13 earned the reputation of being the statute that was proposed specifically to target Catholic schools. Chloe was one of the students who believed Bill 13 was proposed to deliberately force the hand of Catholic school boards:

“I do think the law sets important groundwork for students and gives them some coverage where maybe they didn’t have that, especially in Catholic schools. From what I’ve heard of public schools, at least in the city I grew up in, they do try to protect students in that regard. It’s just different in Catholic schools. I think the bill was proposed with Catholic schools in mind. The bill gives Catholic school students some coverage, so that we don’t feel like we’re completely alone…that we don’t feel like we’re being ignored and subject to the whims of Catholic school authority figures.”

Jaime, who recently graduated from a Catholic high school, completely agreed with Chloe’s sentiments:

“I definitely think that was a huge part of the bill, especially the wording. When I tried to start a GSA in my final year, there were infinite roadblocks. They were saying we weren’t even allowed to use the word “GSA”. Just having that, it was evident that the bill was proposed for Catholic schools because they were banning that term, much less the concept behind it.”

However, not all respondents believed that Bill 13 was proposed based on a mission to target Catholic schools. Several participants believed to the contrary. One of the representatives from WRDSB who has had several occasions to work with members of WCDSB on initiatives meant to support minority youth thought the opposite:

“I honestly don’t think it was developed just to give Catholic school boards specific direction. There’s lots of Ontario public school boards, non-Catholic, secular ones, that have not done a lot in this area, so this is for them as well. I hope this isn’t seen as a law for Catholic school boards. It’s for everybody!”

Mike also thought that the bill was not just meant to help LGBT youth in Catholic schools. He pointed out that many others apart from LGBT students would benefit from the amendments proposed by Bill 13:

“I think there’s a lot of misunderstanding about it because a lot of the pushback comes from people who believe that this is a gay celebration document almost, and only focus on that one issue. Not only does the bill works to address the growing number of students who are struggling because of pushback against their sexual identities, it also talks about other forms of bullying on the rise, like cyber-bullying. I think that there needs to be a lot more awareness about what the bill actually does and how it doesn’t seek to give special privileges to gay youth in Catholic schools.”

Strengths of Bill 13

Naming school clubs “Gay-Straight Alliances”. Because the participants had an overwhelming positive response to the legislation of Bill 13, it was no surprise that many of them found certain aspects of the bill personally appealing and relevant. For example, a lot of the participants found the section of the bill that explicitly forbade Ontario boards and principals from prohibiting the establishment of GSAs and LGBT-affirming clubs in schools as an important amendment in the bill. More so, respondents appreciated the fact that the section also specified that boards must allow students to name their clubs “Gay-Straight Alliances”, if they desired to do so. Prior to the legislation of the bill, some advocates felt that the provincial government allowed Catholic boards to get away with suppressing the needs of LGBT youth. As one of the trustees expressed with frustration:

“The law is only as good as the people prepared to enforce it. And quite honestly, before Bill 13, the provincial government was not ready to enforce it, or at least push the envelope. It didn’t matter that they had policies on safety and progressive discipline; they still allowed our coterminous board, the Catholic school board, to prohibit students from forming clubs and naming their clubs “Gay-Straight Alliances”. They still allowed the Catholic school board to indulge with discriminatory practices, and I think it was for political reasons.”

The bill’s language. Another related point that respondents found very important was the language used in the bill. Many of the interviewees were pleased that the language used was strong yet open and flexible enough to back advocates up in terms of letting them create LGBT-affirming initiatives suited to their schools’ needs and settings. Because they found that their circumstances were not always necessarily the same or ideal as those in other schools, many respondents were relieved to see that the verbiage used in the bill gave them enough freedom to be creative so that they could navigate their unique challenges in their own schools. One teacher explained:

“There’s enough flexibility within that legislation to respect religious beliefs or specific issues of different people, but also respect the fact that these are our students and they have real problems. They need our support and it’s just been too long that we’ve turned a blind eye to their suffering.”

Some participants also liked how the bill’s language encouraged schools to come up with initiatives to improve school climates and become inclusive and supportive of students of any race, ancestry, place of origin, colour, ethnic origin, citizenship, creed, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity/expression, age, marital status, family status, or disability. To them, this clearly meant that the bill was not solely providing special treatment for LGBT youth in the way some conservative critics claimed. One service provider pointed out that others seemed to forget that Bill 13 was developed to support all marginalized students, but added, “We all know that LGBT kids need it the most.”

New surveys and other strengths. Several of the respondents conveyed their interest in the idea that the bill mandated the establishment of new and more specific surveys and reports on bullying and issues connected to negative school climates every two years, on top of more general surveys and reports already being implemented. They felt that if the right people implemented the surveys and responded to its findings on a regular basis, there would be a consistent form of assessment of the LGBT-affirming initiatives that schools were implementing. As one of the service providers commented:

“The other piece that I found interesting was that there’s going to be a new survey required that’s supposed to be done every two years that would track what schools have been doing in response to the directives of the bill. That would be a cool way to impose a check and balance.”

Other components of the bill that participants believed were assets to the overall strength of Bill 13 as a statute proposing new amendments to the Education Act (OLA, 1990) included: 1) the explicit addition of cyber-bullying in the description of bullying offenses for schools to address; 2) the specific duties and responsibilities of the Education Minister, school boards, and principals that were laid out in detail; and 3) the increased focus on the importance of observing the principles of progressive discipline, particularly with regards to involving parents and members of the community in the rehabilitation of repeat offenders, and placing the provision of necessary supports for youth such as counselling at par with the attention to disciplinary actions. Some of the respondents said that the bill was able to raise the observance and respect for the principles of progressive discipline and restorative justice to a higher level.

Weaknesses of Bill 13

Not mandating the name “Gay-Straight Alliances”. Some participants found certain aspects of the bill weak. For one, although certain participants found the section of the bill that mandates Ontario boards to support the formation of LGBT-affirming clubs in schools to be a strong part of the bill, other participants criticized the bill for not specifically insisting that all the clubs be named “Gay-Straight Alliances”. For some, it was important to them that schools acknowledged the word “gay” by accepting the name “GSA”; while for others, it was just as important to acknowledge the word “alliance” because it honoured the solidarity that straight allies show in the clubs. One of the representatives at the board level shared her views on this issue:

“There was just the one word in that section. That part where it says that students “may” call them GSAs, but to me it wasn’t strong enough. I can’t remember exactly how all the wording was written…but my stand is…if they are GSAs, then they should be called GSAs. They shouldn’t be called something else. That’s what we hear from students. In the Catholic board, they call them equity groups or something else.”

No specific support for advocates. Another criticism participants had of Bill 13 was that none of the sections that mandated schools to come up with initiatives to foster accepting and inclusive climates mentioned anything explicit about promoting supports for teachers and staff advocating for marginalized youth. Although the respondents conceded that the bill was primarily conceived to address the needs of minority youth, they pointed out that if the bill had specific mandates that encouraged or required supports for advocates in the schools, the youth would have indirectly but significantly benefited too. In the earlier part of their interviews, many of the respondents extoled the merits of students having adult role models who identified as LGBT in their schools. The participants said that the bill missed an opportunity to help LGBT youth in that manner, by failing to explicitly add amendments that would ensure protections for school employees if they decided to identify as LGBT. Some of the respondents also said that advocates in the schools were in sore need of additional resources and reprieve from compassion and carer fatigue brought on by years of struggle and continued advocacy. They criticized the bill for not including strong enough elements and directions that would promote positive climates in support of hard-working advocates for LGBT students. One teacher clarified how support for advocates in the bill would have helped:

“There have been people who said, I know the teachers who run the GSAs are getting burnt out. So I think we need more supports, we need more release time to go and do some training for us around the more difficult issues. We do have kids that have a higher rate of suicide attempts and depression in our clubs than other clubs. I think, if you want the GSAs to keep going, you have to support the people who are passionate about it by giving them the skills that they need to deal with these kids’ issues because I know of amazing people that have stepped away from this club. You need a larger skill set than just being a nice teacher who gets the issues, right?”

Leaving Gay-Straight Alliances only as an option. Lastly, some participants felt strongly that Bill 13 should not merely be mandating Ontario boards to allow the creation of GSAs in schools if students requested for them. For these participants, the benefit of having GSAs in schools has already been well documented and that the government should no longer be leaving schools the option to wait for students to ask for them. Instead, these respondents believed that the bill should already be unequivocally directing all district boards in the province to create GSAs in each of their schools. A trustee from the Catholic school board had much to say about this point:

“If you look at the secular system, every single public high school in Waterloo Region, and even some of the senior elementary, has a GSA. In Waterloo Catholic, we have 5 of the largest high schools in the region, and only two of them have a club like a GSA. The implementation approach that we’re taking is if students ask for them, we’ll permit a GSA. The reality is, these are vulnerable students. A GSA is a policy tool that works. The fact that every public school has one, and we’re among the largest, shows that the demand is there. The argument that we’re waiting for students to come up and ask for one to show that there’s actually a need for it just doesn’t make sense. The problem I come back to often is that trustees need to play a leadership role. We’re not playing that leadership role!”

Dichotomy in Standpoints

In the analysis of the participants’ perspectives on the strengths and weaknesses of the different aspects and components of Bill 13, a distinct dichotomy in standpoints became discernible under early scrutiny. While there were many occasions when participants appreciated the specificity of certain aspects and components of the bill because they believed it was completely necessary for it to be effective, there were other times when they underscored the merits of having some of the bill’s aspects and components stated in more general terms to allow for flexibility so that stakeholders could be more creative in coming up with strategies and programs that were more customized to the needs of their LGBT students. On one end of the dichotomy, respondents emphasized the importance of specificity in the bill’s verbiage so that desired outcomes could be achieved promptly; on the other end, they also made a point of noting how useful it is for parts of the bill to allow for flexibility that would permit advocates to tailor initiatives in their efforts to navigate challenges they encountered along the way.

Specificity. Participants lauded several aspects and components of Bill 13 because of their specificity and explicitness, which the participants believed significantly contributed to the strengths of the statute. They particularly respected the fact that the bill specifically forbade school boards and principals from prohibiting students to form groups that promoted safety, diversity, equity, and inclusion, including GSAs and LGBT-affirming clubs. They also appreciated the bill’s explicit mandate that school boards and principals unconditionally allow students to call their clubs “Gay-Straight Alliances”, if they chose to do so. These directives were clear and non-negotiable, and provided the necessary sanctions for LGBT youth to create GSAs and other similar clubs.

Two of the board trustees who participated in the study commented that they believed it was appropriate for the bill to mandate boards to allow students to call their clubs by any name they wanted. One trustee from the Catholic school board elaborated:

“I think fundamentally, the real issue was “What name are we going to use?” That was what the opposing sides within the Catholic school system started fighting over. And the reason why that becomes important, is not because the name necessarily matters, it’s because the name becomes a symbolic issue that is either saying “We’re okay with the word ‘gay’.” Or “We’re not okay with the word ‘gay’.”and by extension, we’re not okay with you coming to our school if you’re gay. My sense is more, if you let kids call it what they want, then it encourages them. Whatever language they find most affirming to them, you give them the freedom to use it.”

Participants were pleased to know that new surveys were going to be implemented that would specifically monitor and evaluate the effectiveness of the school boards’ policies and programs related to the bill’s new goals. Apart from the already existing surveys to examine school climates, these new surveys were going to be implemented to track the progress of the schools’ initiatives in response to the other mandates of the bill. Students were comforted to know that Bill 13 explicitly added cyber-bullying as an offense that warranted disciplinary action under the bullying section of the bill because they knew more than anyone else how rampant online harassment could be as it was mostly done covertly and insidiously. In relation to disciplinary actions, many participants expressed praise for the increased focus on the principles of progressive discipline in the specified and detailed duties and responsibilities of the Education Minister, school boards, and principals that were distinctly outlined in the bill. They noted how important it was to explicitly mandate that school employees who inform principals of any reportable incident must be included in the discussion on the subsequent steps to be taken in the investigation process of the incident. They also noted the importance of including the parents or guardians of both the student they believed was bullied, and the student they believed to have engaged in the bullying, in these discussions. Consequently, they recognized the value of the bill’s specific inclusion of the community’s role in the implementation of progressive discipline.

Participants commended the specific mandate for principals to pay close attention not only to the corresponding disciplinary actions warranted in bullying incidents, but also to the provision of supports such as counselling for the students who were bullied, witnessed the bullying, and engaged in the bullying. They believed this not only showed concern for justice and fairness but also for the welfare of all students involved.

Apart from mandating support for the creation of GSAs in schools, Bill 13 also explicitly included directives for school boards to provide annual professional development in-service trainings and workshops for staff on bullying prevention and the promotion of positive school climates; create equity and inclusion educational policies that would address the incorporation of elements promoting diversity in school curricula; provide counselling services using the expertise of psychologists, social workers, and other professionals who can address conflicts related to bullying of all kinds; and submit annual reports to the Education Minister with respect to suspensions, expulsions, and other disciplinary actions related to harassment and discrimination.

One of the representatives from the board who work closely with teacher GSA sponsors emphasized how professional development in-service trainings were able to help make the link between the role of school curricula and advocacy more apparent, and encouraged teachers to incorporate LGBT topics into their lesson plans. One teacher mentioned something related to this point, “We’ve had in-service on how to incorporate diversity and inclusion into lesson plans. Last year there was information sent to staff on tips to broach certain topics. The understanding is that you shouldn’t just be sticking to your old habits.”

It was apparent from their responses that the participants truly believed that certain mandates needed to be expressed as explicitly as possible. The more specific certain aspects and components of the bill were, the less room for excuses and negotiation in their implementation. The participants just as clearly emphasized this appreciation for explicitness when they expressed disappointment in the lack of specificity regarding certain sections of the bill.

One major disappointment among the advocates for LGBT youth was the fact that they did not find enough elements in any of the sections that outlined mandates for providing supports in schools that specified increasing resources for school staff who devote their time and energies to fostering positive school climates that are safe and inclusive for all students. It was their hope that in some way policymakers would recognize that by supporting minority students’ advocates they would indirectly but effectively be supporting the students too. Save for the mandate on requiring school boards to provide annual professional development in-service trainings for school staff, the participants were not aware of any other supports that were specified to help advocates. Issues concerning protections for staff who openly identify as sexual and gender minorities, the need for more adult sexual and gender minority role models for youth, and compassion and carer fatigue were brought up. The lack of any mandates to address these issues served as a source of frustration for some participants.

Two related aspects of the bill that some participants found lacking specificity were the sections that allowed for the creation of LGBT-affirming clubs in schools and the naming of these clubs “Gay-Straight Alliances”, if students desired to do so. Apparently, although some participants found these aspects specific enough to provide necessary supports for LGBT students, others thought that simply forbidding school boards from prohibiting students from forming LGBT-affirming clubs and calling them “Gay-Straight Alliances” was not quite specific enough. For these participants, since Ontario publicly funded both secular and Catholic schools, it would have been best if Bill 13 explicitly mandated all publicly-funded school boards to create GSAs in all their schools and made sure that they were not called any other name.

These differences in perspectives created a dichotomy that raised the question on where policymakers should push or draw the line on being specific in the content of their proposed bills. Some participants argued that there was also value in keeping aspects and components of the bill open or general enough to allow for flexibility so that stakeholders could devise creative solutions to navigate challenges that they encounter in their own particular settings. Depending on the reasoning of a stakeholder, a strong argument could be made for either of these opposing perspectives.

Flexibility. Several participants believed that the more general and encompassing certain statements of Bill 13 were, the more flexibility they afforded to the stakeholders who were expected to implement initiatives developed to adhere to the bill’s mandates. For example, although respondents noted that the sub-section of the bill that mandates school boards to “promote a positive school climate that is inclusive and accepting of all pupils” goes on to specify “including pupils of any race, ancestry, place of origin, colour, ethnic origin, citizenship, creed, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, gender expression, age, marital status, family status or disability” (OLA, 2012, p.3), they still believed that the statement was general enough to allow for flexibility because it did not go on to say exactly how school boards were supposed to promote a positive school climate. This statement was not only specific enough to establish that the mandate was not just directed for the benefit of sexual and gender minority youth in schools, squashing the nonsensical claim of conservatives that the bill was proposed solely for the purpose of providing LGBT individuals special treatment; it was still general enough to afford the flexibility required to allow room for individual creativity and customization on the part of school boards’ implementation of initiatives to respond to the bill’s mandate. This flexibility that allowed for customization in the implementation of initiatives to respond to the bill’s mandate was passed down to individual schools, which as many participants repeatedly pointed out, were different and unique from one another in many ways.

For the participants who saw the merit of having some aspects and components of Bill 13 affording flexibility in the implementation of initiatives to support LGBT youth, the prospect of being able to more freely develop and establish different strategies and initiatives that could stimulate the interest of new advocates into joining any of the community coalitions working towards the promotion of positive school climates was a welcome advantage. They believed that with more opportunities to create a greater variety of LGBT-affirming initiatives, strategies, and policies, there would be more for prospective new advocates to choose from that would fit their convictions, available time and resources, degrees of commitment, and comfort levels. These participants also saw this flexibility as a quality that would permit them enough leeway to find ways to implement sought-after initiatives, such as the creation of gender-neutral washrooms in schools, which did not necessarily fall under any of the specific mandates of Bill 13.

Another example participants gave to support the merits of having certain aspects and components of Bill 13 affording flexibility, and some degree of openness to interpretation, is the aspect where the bill made it clear that its mandates were created for “all publicly-funded schools” to follow. Although many participants chose to interpret this statement in the same way that most of the Ontario public chose to interpret it, which was that it was to include Catholic high schools, some participants chose to interpret it as a directive and reason to extend their efforts to help LGBT youth in secular elementary and middle schools. Some advocates chose to interpret this mandate as a push to create more GSAs and LGBT-affirming initiatives in their elementary and middle schools.

One teacher confessed, “For me personally, the next step is obvious. We should have GSAs or something…some sort of initiative in elementary schools that show how we connect, regardless of our differences.” Another teacher shared her thoughts about expanding LGBT-affirming initiatives to middle schools:

“We’ve had a GSA here for five years. There are maybe only two others that run at the [senior] elementary level. People come to our school and say, “You’re allowed to say that in class when you talk about gay marriage? You read novels with gay characters?” More schools should be able to do more at the [senior] elementary level. With this bill, I hope things will change.”

Based on the participants’ responses, they believed that affording flexibility in the language and content of the bill was just as important as exercising specificity when it was needed. Although these views typically represent the opposite ends of any important deliberation, it can be argued that such a dichotomy in perspectives need not be perceived as a dilemma. The merits of exercising specificity in the verbiage and contents of the bill would not necessarily preclude the merits of affording flexibility in some of its aspects and components. The merits from each end of the dichotomy are not exclusive of one another, and this dialectical nature would only enhance the rigour in the process of determining the most beneficial times to exercise specificity over flexibility, or afford flexibility over specificity, in certain aspects and components of a policy or bill. This would be particularly true if the bill was carefully developed and constructed to contain both specificity and flexibility in different parts of its entirety.

Benefits Resulting from the Legislation of Bill 13

Unqualified backing. When the topic of potential benefits resulting from the legislation of Bill 13 came up, many of the respondents got excited during the interviews. It seemed that the prospect of positive outcomes resulting from Bill 13 was something that inspired and stimulated the key stakeholders. For the majority of respondents, there were going to be obvious benefits to the legislation and enactment of Bill 13. The most obvious would be, that for advocates like them, they would have the unqualified legal backing to carry out strategies and initiatives that they knew were effective in supporting LGBT youth. Not only would they be able to carry out current work that helped LGBT students without trepidation, but they would also be able to initiate new LGBT-affirming initiatives in their schools with more confidence. For advocates who had doubts or fears of repercussions when others questioned their efforts, they would have the sanction they need to reinforce their positions.

One representative at the administration level of the board indicated that school boards would then have all the justification they needed to support minority youth. She quipped, “I didn’t know how much longer the Liberal government was planning on staying subtle. I’m glad they finally did this.” Another representative at the administration level pointed out that the legislation of the bill would not only provide stakeholders more backing, but it would also give boards the strong push they need. For advocates in schools who have already been quietly working under the radar to help LGBT youth, opportunities might come up for them to officially work on their projects as boards would have to find ways to respond to the mandate to develop more positive school climates. A few teachers admitted to feeling safer knowing that the law would be behind them. Other teachers, on the other hand, said that the new act would provide them greater motivation to work harder on their advocacy for their LGBT youth.

Ariel remarked, “The bill’s enactment will show that the government is in support of tolerance, acceptance, and equality. It’s also an indication that society is changing and that our leaders are responding to the change.” The superintendent commented that the passing of Bill 13 is “a public endorsement that cannot be ignored”, and added, “schools should take advantage of the message the government has conveyed”.

Some participants sounded more assured and confident than the rest with the idea that with explicit mandates of the new law, advocates would certainly have what they need to make their efforts count even more. Alice commented that the benefit of having Bill 13 passed is “it will tell teachers and school staff where they should stand”. Sara interjected, “At least now, students will know their school will have to follow the law.” Although she knows that things are not necessarily as simple as school boards automatically following all the dictates of the law, the school administrator still remarked, “It’s non-negotiable now. The law will be there to hold schools accountable.”

Mary felt that Bill 13 would give more voice to the sentiments of marginalized LGBT youth and their advocates – “a voice that can no longer be silenced by religious conservatives.” When the legislation of Bill 13 was imminent, a trustee from the Catholic board who was upset about the controversy on using the name “GSA” retorted, “Okay, call it a GSA, don’t call it a GSA, but let’s get something started in the schools. You’ve got the support from the province now. Let’s make that happen.” The school administrator shared this sentiment as well, “Whether it will be called PRISM (i.e., Pride and Respect for Individuals of a Sexual Minority) or not…I know one of the other schools wants to use our name PRISM…we’re going to get some form of group in every Catholic high school in Waterloo Region by next year.”

Rallying the troops. Several of the respondents thought that Bill 13 would be able to act as an accelerant to the advocacy efforts of the stakeholders in Waterloo Region. Whereas before its legislation, efforts to form GSAs or similar clubs and implement LGBT-affirming initiatives were bogged down by administration concerns of parental pushback and other complaints, advocates now believed that Bill 13 can help fast-forward initiatives started by community coalition members in schools. There was also the notion among the interviewees that with Bill 13 passed as law, there would be more opportunities and confidence to rally other school personnel to become new advocates for the cause of supporting sexual and gender minority youth. One of the public school teachers pointed out that it seemed that, in the past, the bulk of school staff refused to get involved because of fears of repercussions. He believed that with approbation from the government, more teachers, counsellors, and other employees would be able to step up and offer their support in their own ways:

“Before Bill 13 was passed, we were on an island and we didn’t know what the next action to support these kids was going to be because we could get into a whole heap of hot water with the board. So then I think, what happened was, about 80% of the staff that were in the middle, who were on the fence, just sat there and said, “I’m not getting involved.” Whereas now, we have the freedom to say, if you’re in that 80%, get involved and help!”

Another teacher emphasized that the law would sanction more activities related to finding new ways to support minority youth in schools, which would provide new advocates different options to choose from so that they could offer support at their comfort level. More importantly, she believed that long-time advocates could take advantage of the opportunities provided by Bill 13 to educate more individuals within and outside of the school community about LGBT youth needs and rights because more people would likely be more open to persuasion with the new law in place. She was convinced that there would be more opportunities to get more advocates for their cause without having to force anyone into changing entire belief systems. A teacher from a Catholic school had similar ideas when she expressed that the new act would provide occasions for recruiting people who have been “on the fence for a long time”, and that with successful recruitment, “There would be more people on board.”

Supporting existing initiatives and jumpstarting new ones. Several interviewees pointed out that with the new act, there will no longer be a risk for existing GSAs and LGBT-affirming initiatives facing opposition in their schools from being removed or abolished. They thought that with the government mandate, struggling GSAs and LGBT-affirming initiatives could at least have a better chance of getting more support in terms of leadership from teachers, staff, and administrators, as well as funding from their schools. Also, with certain sections of the bill that were general and open enough to allow for greater flexibility and creativity in the establishment of initiatives that would promote school climates inclusive and accepting of all pupils, LGBT students and their advocates saw the potential for them to be able to develop new strategies, initiatives, and policies that would address persistent as well as emerging issues.

Sydney wondered, “Maybe now we can get gender-neutral washrooms set up on some floors.” Ariel underscored the fact that the new act was not just about pushing schools to establish or support GSAs but also encouraging them to come up with more ideas on how to make the school climates safer, more inclusive, and accepting. Helen, who is part of an active GSA, hoped that their school administration would ask their teachers to include more LGBT history and culture in their curriculum. One teacher commented that advocacy in the various schools affiliated with the two boards of Waterloo Region looked very different from one school to the next because each school was unique and had distinct circumstances. She conceded that some schools were more advanced with their success in helping LGBT youth, while others definitely needed help getting their initiatives going. Another teacher revealed:

“Many of the existing GSAs are still struggling. Perhaps this directive from the government could breathe new life to those GSAs. There are teachers and child and youth workers out there who have needed support to help these kids. Everyone could certainly use more resources too. So there’s still more room for improvement with the GSAs we already have.”

Since Bill 13 would sanction any initiative that would help promote positive school climates inclusive and accepting of all students, its legislation inspired new ideas from the participants who thought that there could still be so much that could be done in Waterloo Region. One idea that many participants shared was the creation of more GSAs in their senior elementary/middle schools. Mary had very strong feelings about this idea:

“The most important part now is that there could be a safe space in every school. So no student is feeling that they don’t have anywhere to go in school. Some parents might not like the idea of GSAs in middle school. They may not like that LGBT material is being taught at that age. But tough, they have to suck it up. We’ve been the ones at the tail end of things for so long! They should realize it’s about kids, not them. They think they know better, but really, they don’t. The law will even things up for us now!”

Both representatives from the public board who have been working on equity and inclusion projects for years also had thoughts about new opportunities to help younger students that could stem from the enactment of Bill 13. One board representative said, “With our board, it will help us expand and start GSAs in more of our senior elementary schools. With the other board, well, they don’t have clubs yet in their Grades 7 and 8. So we’ll see.” The other representative revealed:

“We’ve heard from teachers how some students in middle schools love talking to older kids from high school about starting up GSAs. Maybe we can even network GSAs between middle and high schools so that the older kids can mentor and support the younger ones even more.”

The superintendent mentioned that cross-grade interactions would be encouraged if their region’s GSA network would have more GSAs in their elementary schools. One service provider who was responsible for maintaining the region’s GSA Network website confirmed that these interactions were already ongoing online and that younger students really appreciated the chance to reach out to older youth who could mentor them.

A more obvious idea that many of the participants expressed was the notion that with the new act, students in the three remaining Catholic high schools in Waterloo Region would be able to form their own clubs similar to PRISM, as well as celebrate LGBT-positive events and campaigns, with the support of the advocates from their schools. Shaun, Ariel, and Sydney all mentioned that they had non-Catholic friends who studied at Catholic high schools and it was a relief to know that their friends could finally start their own GSA-type clubs and request for LGBT-focused activities.

Keith made a point to emphasize that it was his hope that with the creativity and flexibility that Bill 13 inspired and allowed, schools in rural areas would also be able to begin looking into new ways of establishing LGBT-affirming initiatives such as incorporating inclusive material in their curricula, as well as creating connections to community agencies with LGBT-specific knowledge and resources for isolated youth. One trustee shared that his hope was that the new act would encourage schools to want to do more than just be able to “tick off the box and claim that they have already fulfilled what the law has required of them” and not just execute the bare minimum.

Dialogue drawing attention to the cause. Participants saw that the proposal and legislation of Bill 13 already resulted in an unintended outcome that from their perspective was actually something positive. Many of the respondents, especially the teachers and the administrator, thought that despite the tension that was raised by the debates on Bill 13 between conservative and liberal factions of the larger community, it was gratifying to know that it also raised awareness and intelligent conversations about LGBT issues in the process. One teacher said that the more dialogue the bill’s legislation produced, the higher the profile it created for LGBT human rights and the importance of keeping our sexual and gender minority youth safe in schools. Another teacher was giggling when she commented:

“I didn’t think I’d ever hear the Archbishop of Toronto ever say the word ‘gay’ because Catholic Church conservatives always want to use awkward terms like ‘same-sex attracted’. But there he was on broadcast radio, talking as if he was still on a pulpit. He kept using the word ‘gay’ over and over. I thought it was hilarious! I bet that his message got a lot of heated conversations going. I’m sure all that discussion brought attention to the plight of our LGBT students, which for me was certainly a plus.”

Challenges Resulting from the Legislation of Bill 13

Implementation challenges. There were moments in the interviews that highlighted the participants’ concerns about potential challenges that could result from the legislation of Bill 13. Among the different challenges that they could foresee, the one that many respondents were concerned about was how the mandates of the bill were going to be implemented, particularly the sections that did not have explicit details with regards to implementation. This is what Helen implied when she asked, “Like all of a sudden the bill is supposed to make kids feel safe once it’s passed?” She was concerned that having such a law might make some people become complacent instead of inspired to make use of the opportunities that the law would present. One teacher noted that people should remember that there has to be a change at the school level once the law comes into effect. She cited, “certain policies on curricular changes that were established in the early 2000s were never really implemented in our school”. She was afraid that this new act would not bring in any significant change unless advocates remained vigilant and remembered to consistently make the most out of its directives. Another teacher could not curb her cynicism and retorted, “It doesn’t solve everything though. It will depend a lot on how it is disseminated and enforced.” One of the representatives at the administration level of the public board was more positive in her outlook and said, “The implementation of the act will look different in each school. That’s just the nature of legislation and policies. People will really have to go for it once the bill’s passed as law.”

Some participants’ concerns on the implementation of the mandates of Bill 13 were more specific and practical. One teacher remarked, “One of the big challenges for us is choosing the right people who would become involved with the planning and implementing of initiatives meant to help students. It’s important that we look into their background, attitudes, qualifications…even lived experience.” Her statement was very similar to a comment of another teacher who wanted to make sure that when it came to the implementation of LGBT-affirming initiatives in schools, the personnel who would lead and take responsibility for the initiatives not only need to have the appropriate credentials and experience, but also the right values and convictions to do the work. The superintendent commented that choosing the right people for leadership roles was just as important for the purposes of safeguarding the “sustainability of the school’s efforts.”

Procuring and managing resources. Another specific and practical concern related to the implementation of the mandates of Bill 13 involved the procurement and management of resources. Some of the respondents felt that the bill did not pay particular attention to this concern, and that without specific provisions to resources, advocates would have a difficult time carrying out initiatives. There was no doubt that the scarcity of resources was an issue for almost all of the advocates from the school community, the different levels of the school board, and the external agencies who provided additional support to the Waterloo Region LGBT students. Students, teachers, and service providers in particular, all expressed the need for resources in order to carry out needed initiatives. One teacher remarked, “Even with the enthusiasm of the students and the manpower provided by faculty and staff who devote their time and energy after school hours, without the necessary resources, initiatives are limited and people become demoralized.”

One of the service providers was already anticipating an increased demand for their support once the bill passes, “Schools know that they can come to us for additional counselling, professional development training and workshops, books, DVDs, and the use of the region’s GSA Network website. Once Bill 13 becomes law, there will be more demand and limited supply.” One of the board representatives who is consistently involved with work dedicated to GSAs offered some optimism by suggesting that, because lack of resources is an issue for everyone, people will have to find ways to be more creative, flexible, and resourceful:

“The funds aren’t always there. So I always encourage our GSA leaders to approach their vice-principal for student activities and ask for funds if they want to run an event because that’s their right; students pay for that in their fees. If they want to do some sort of initiative, like get a speaker, or if they want an outing…they need some money, they should ask their school for it!”

One of the trustees had a near identical suggestion as a solution to the problem of scarce resources for implementing activities, “Funding’s always an issue at the board level. You can say that about special education needs, infrastructure…funding’s always an issue. But students can ask for money from their school’s budget if they need it.” Another trustee pointed out that the allocation of resources for amendments and specific mandates of education legislation are not really included in the bill itself, and that it usually follows later in other documents created by the Ministry of Education, based on a budget. So details of how resources would be allocated for directed initiatives in the content of the bill are not something people should actually expect to find on the bill itself. However, he expressed that he did understand that what advocates were likely looking for were directives on the bill specifying that the Education Minister should allocate resources for supports required by its other mandates, and not just more directives to create more policies and initiatives for school boards.

Evaluation challenges. Apart from the need for more resources and having the right people involved in the establishment of GSAs and the implementation of LGBT-affirming initiatives in response to the legislation of Bill 13, another challenge associated with implementation that the respondents noted was the proper evaluation of school boards’ efforts to create positive climates for minority youth. One teacher raised the question, “How exactly does the government intend to check if the act is being enforced?” Some participants were not convinced that additional surveys specifically conducted to evaluate efforts in response to Bill13’s mandates would be enough to track changes over time. Although other participants had related doubts about performance and response evaluation, they also felt that it was everyone’s responsibility to ensure and check that the directives of the act were followed, and not just the government’s.

In relation to some participants’ concerns about the lack of specific details and explicit directions regarding the implementation and evaluation of initiatives in accordance to Bill 13’s mandates, several respondents from the school board level were careful to point out that these details and directions are usually specified and outlined in the creation of documents containing procedures and guidelines that follow after the legislation of a bill. They also noted that many times, policymakers purposely hold back on adding specifics in certain aspects of a bill in order to allow key stakeholders to customize their initiatives or solutions to the context of their own settings.

Public pushback. One last major challenge that participants anticipated with the enactment of the bill was the possibility that the heated debates between members of society with opposing opinions on Bill 13 would escalate. There were already months of building tension due to the pushback from the conservative sector against the liberal government’s proposal to require all publicly-funded (secular and Catholic) school boards to support LGBT-affirming clubs in schools and allow students to call them “Gay-Straight Alliances”, if they chose to do so. The religious sector of Ontario claimed that the bill was part of the government’s agenda to push their liberal ideas in schools. However, it was noticeable that it was the participants interviewed before the bill was passed in June 2012 who mostly expressed this apprehension. The concern about more pushback and greater tension building significantly diminished among participants interviewed after the bill was enacted as law, and particularly, after a statement was released by the Catholic bishops of Ontario announcing they were not going to promote or tolerate any form of civil disobedience to Bill 13 as a new law (Mann, 2012).

Discussion

According to McCaskell (2005), any initiative or strategy dedicated to combatting marginalization and oppression, particularly in school systems, could only be effective if it combined three important determinants: education, rules with consequences, and political action. If this assertion were accurate, it would make education legislation an ideal intervention to fill the bill. Fetner and Kush (2007) previously endorsed the development of legislation and public policy favouring LGBT students and their rights to promote transformative change in school systems. They argued that if anti-discrimination policies were combined with anti-bullying policies, it would not only provide protections for LGBT students, but it would also send an important message to society in support of LGBT rights. Robinson and Espelage (2012) reinforced this message by directing this appeal to progressive political leaders who they believe are pivotal for securing a higher level of change in society. Our study participants could not have agreed more, asserting that legislation is the next important step to ensuring that efforts to create positive school climates for LGBT youth are both legally mandated and made socially sustainable.

Although researchers have expressed the value of legislation in the advocacy for LGBT youth mental health and wellbeing in schools (Fetner & Kush, 2007; Robinson & Espelage, 2012), there are not that many discussions based on empirical research studies in published academic literature that have explored the role of legislation in such advocacy, leaving its implicit value mostly still unexamined and unexplored. Academic literature has already examined and explored how change happens in schools so that advocacy and action to support LGBT youth mental health and wellbeing can be initiated and even sustained (Fisher et al., 2008; Hansen, 2007). The role of the strength of the commitment of advocates and the implementation of initiatives that have been documented to be empirically sound and successful in providing supports for LGBT youth have been extensively discussed in peer-reviewed journal articles (Hansen, 2007; Hunter, 2007). In their study on how to make Ontario school climates safer and more inclusive, Kitchen and Bellini (2013) found evidence that positive policy direction from government is critical in advocating for the mental health and wellbeing of LGBT youth in schools, supporting arguments that push for LGBT-affirming education legislation made by other Canadian researchers (Anderson, 2014; Liboro et al., 2015; McCaskell, 2005; Rayside, 2014; St. John et al., 2014). In the analysis of their interviews of 41 educators working with GSAs, Kitchen and Bellini’s (2013) data suggested that Ontario policy had a positive impact on school climates for LGBT youth, in particular, decreasing negative experiences among LGBT youth in hostile school environments that have been linked in previous research with increased rates of depression and suicide attempts (Hatzenbuehler, 2011).