For many years, psychology in Puerto Rico was considered an individual-level positivistic science with a neutral stance towards socio-political issues. However, during recent years psychologists on the Island have become more involved in policy issues. Initially this was the result of the pioneering work of some individuals. More recently, systematic efforts have been supported by research within the social-community psychology program at the University of Puerto Rico and by the Puerto Rico Psychology Association (PRPA). Results of these studies showed that most psychologists who did not participate in policy work had one of the following reasons: a) lack of time, b) lack of training, and/or c) negative attitudes toward party politics. However, there are examples of work in public policy as a result of individual efforts, from NGOs, the PRPA, governmental agencies, and private practitioners. Regarding training, research demonstrated that there are hardly any courses on the subject in graduate programs, nor emphasis on the competencies required for the task in the available curriculum. There are also few publications about psychologists and public policy. This article will:

Por muchos años la psicología en Puerto Rico se consideraba una ciencia positivista de intervenciones a nivel individual con una postura neutral hacia asuntos socio-políticos. Sin embargo, en años recientes los psicólogos/as en la Isla se han involucrado más en política pública. Inicialmente este fue el resultado del trabajo de algunos pioneros/as. Algunos esfuerzos sistemáticos han sido apoyados por investigaciones desde el Área Social-Comunitaria de la Universidad de Puerto Rico y por la Asociación de Psicología de P.R (APPR). Las investigaciones demostraron que la mayoría de los psicólogos/as que no participan en política pública, no lo hacen por: a) falta de tiempo, b) falta de adiestramiento y c) actitudes negativas hacia el proceso político partidista. Ejemplos de la práctica surgen de esfuerzos individuales, organizaciones sin fines de lucro, de la APPR, desde entidades gubernamentales y desde la práctica privada. Son escasas las publicaciones sobre política pública. Los estudios también revelaron que casi no hay cursos sobre el tema en los programas graduados ni énfasis en las competencias requeridas para estas tareas en el currículo. En este artículo

Please download the PDF for the complete article including tables and figures.

Community psychology is committed to the pursuit of social change and social justice (Serrano-García, Carvallo, & Walters, 2009). It pursues these goals through diverse and interlocking levels of intervention which include the individual, group, community, organizational, and policy levels. Although the emphasis on policy is relatively recent, it has gained great momentum as one of the areas of disciplinary growth in the United States (Maton, 2013; Phillips, 2000).

In Puerto Rico, psychology was considered an individual-level positivistic science, which should hold a neutral stance towards social and political issues. Although some still think this way, much has changed including an increasing interest in policy. For many years there were isolated efforts to work at this level. These efforts have increased and have been spurred mainly by social-community and clinical-community psychologists. Thus, the purpose of this article is to:

Special emphasis will be placed on the roles community psychologists[1] have played in this transformation.

The article has various sections including

The descriptions and analysis presented considers a PP process encompassing six phases:

This process can emanate from government entities (top-down) or from the citizenry, either individually or collectively (bottom-up; Dobelstein, 1997).

Description of Efforts to Foster Participation of Psychologists in Public Policy

Modeling: Individual Efforts

Although most psychologists in Puerto Rico do not have policy training, there are several individuals who have immersed themselves in this arena. These precursors began their work before policy was conceptualized as a task for psychologists. Some examples of early pioneers as well as current exponents are presented in Table 1 (Boulón-Díaz, 2007; Moreno-Velázquez, Justel-Cabrera & Massanet-Rosario, 2007; Roca de Torres, 2007). These individuals serve as role models and provide evidence of psychologists’ competence for key roles within government. Their contributions paved the way for other psychologists who want to assume policy as a possible area of intervention.

Table 1: Pioneers and Recent Exponents of Public Policy Efforts in Puerto Rico

Organizational Efforts: The Puerto Rico Psychology Association

Psychology’s public policy efforts have been greatly advanced by the Puerto Rico Psychological Association (PRPA). The PRPA was established in 1954 and from the outset was involved in public policy processes, particularly guild issues. For the first 30 years, it advocated for laws to establish professional regulations and licensing at the Puertorrican legislature. These efforts succeeded in 1983 (Boulón-Díaz, 2006). Although this initial involvement emphasized professional interests, it set the stage for the development of a professional identity that included a role in policy establishment and transformation.

The 1980s was a decade of growth related to policy involvement for the PRPA. At this time the Association began providing expert testimony to the legislature on issues related to mental health, violence prevention, death penalty, psychologically healthy workplace strategies, psychologists in the schools, and LGBT rights and health, among others (APPR, 2014). The manner in which the PRPA managed legislative petitions for expert testimony was by identifying members that possessed expertise in specific areas. These members then provided written and sometimes oral testimony representing the organization. This process still solidifies the PRPA’s sociopolitical role and provides important experiences for members in the policy process.

The use of the media has been central to the PRPA’s involvement in public policy. Since the 1990s there has been a growing presence of the Association in media outlets through newspaper interviews and columns about key social and political issues as well as radio and TV interviews. The Association has also organized press conferences to present specific projects or to establish its position regarding specific social topics or government initiatives. The PRPA’s growth in this area has been outstanding as PRPA’s contributions are included in weekly media reports by various outlets (For examples see Ayala, 2015; Rodríguez, 2015; N.A., 2015).

The growth in media contributions has been accompanied by a steady expansion in the PRPA’s social media presence. The Association now owns accounts on both Facebook and Twitter and an active web page. Although the majority of the posts in social media are related to promoting the PRPA’s activities, it also provides media coverage of policy related efforts. This wide visibility has served to continue validating the role of psychology in public policy.

The increasing involvement of the PRPA in public policy presented the need for the Association to rethink its internal structure to respond to policy issues more effectively. Hence, in 2007 the PRPA created a Standing Committee on Psychology and Public Policy (CPPP) with the goal of streamlining its policy efforts and generating educational reform recommendations to train psychologists for this role. After its creation, the CPPP has been responsible for dozens of expert testimonies, the creation of a public policy course syllabus, and two important initiatives, which we describe in the Practice section: Proposals without Colors and a Clean Electoral Campaign. Unfortunately, in recent years, the CPPP has had setbacks related to the availability of psychologists ready to coordinate its work. This has resulted in a regression toward old styles of policy analysis, centered around the Association’s President. Hence, the PRPA needs to reevaluate its policy priorities and internal structure, which is sustained mostly by volunteers.

Another area of policy involvement for the PRPA has been its participation in public demonstrations. Some examples are its presence in manifestations against the firing of public employees, supporting students’ strike at the state university against a raise in tuition fees, and in favor of the release of Puerto Rican political prisoners. The PRPA has had great success organizing and mobilizing its members and gaining international support for its positions. With this background in mind, the authors turn to reviewing the research done in support of and about public policy.

Research

Psychologists’ Participation in Public Policy

The first study of psychologists’ participation in public policy (PP) in Puerto Rico was carried out by the first author in 1983 and was sponsored by the American Psychological Association (APA). A survey was sent to all PRPA members at the time (n = 300) and 35 psychologists responded of whom 82% reported participating in PP mainly in phases of problem identification and program evaluation. Twenty percent provided expert testimony, and 18% performed research related to PP. A fascinating result was that 60% of participants believed their colleagues did not consider PP a legitimate activity. However, 89% believed psychologists’ participation in PP should increase (Serrano-García, 1983). This shed some light on our profession’s views about the legitimacy of PP as a potential role and the disparity between personal and group views on the issue.

In order to evaluate changes over time, a follow-up study was carried out in 2004. This survey, sent to 516 PRPA members, was able to recruit a larger sample (n = 86). Results revealed that 55% reported participating in PP. The majority of those who participated engaged in problem identification (62%); the most frequent roles were providing expert testimony (32%), preparation of documentation (43%), and consulting (43% government and 38% non-governmental organizations). Most (87%) had not received formal training in public policy. Concerning the legitimacy of this role, 43% still believed their colleagues did not consider public policy work a legitimate activity. Although this shows small attitude change in their views about participation in PP – probably as a result of the efforts previously summarized – the roles that individuals assumed tended to remain constant (Serrano-García, Rosa, & García, 2005).

Policy Related Research

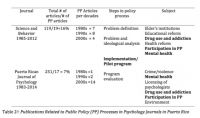

Most psychological research is pertinent to public policy since it is used for problem identification and analysis. However, this article focuses on research explicitly labeled as public policy research published in all issues of the two major psychology journals in Puerto Rico as well as research carried out for theses and dissertations of the Social-Community Psychology Program at the University of Puerto Rico. These journals are the focus of the review because they are the ones where psychologists on the Island publish more frequently: Science and Behavior is published by Carlos Albizu University, a private PhD granting institution, and the Puerto Rican Journal of Psychology (PRJP) is published by the PRPA. Research articles that were identified refer explicitly to one of the six phases of the public policy process. Results of the journals’ analysis are presented in Table 2.

Both journals had a low percentage of public policy articles although Science and Behavior’s percentage is more than twice that of the PRJP. In absolute numbers, the amount of articles about public policy is almost the same; in Science and Behavior the number has decreased in the last decade while in the PRJP it has increased dramatically. Articles focused on the same policy processes, and there were none related to policy approval. Varied areas of interest have been studied although drug use and addiction, mental health, and participation in public policy[2] are present in both journals.

Table 2:

Publications Related to Public Policy (PP) Processes in Psychology Journals in Puerto Rico[3]

We then perused Master’s theses and dissertations of the Social-Community Psychology Program at the University of Puerto Rico. This program is the only program related to the discipline of community psychology on the Island and the authors assumed that, as such, it would have a stronger emphasis on policy issues. The authors discovered 29 theses and dissertations that referred explicitly to public policy processes; their number increased as the decades ensued. Problem and policy analysis were the most frequently studied processes and neither approval of measures nor implementation of policies were researched. Most frequently studied topics included community mental health, community development and HIV/AIDS prevention (Serrano-García, 2014; see Table 3).

Table 3: Policy Studies in MA Theses and PhD Dissertations of the University of Puerto Rico Social-Community Program[4]

The authors also examined methods most frequently used to carry out PP research both in the journals and in theses and dissertations. Identified methods included:

It is apparent that the most employed method was problem analysis, which is consistent with the high levels of psychologists’ participation in the problem identification phase. However, through the decades, there has been a progressive diversification of methods and topics.

In conclusion, policy research by psychologists is not frequent on the Island but has been increasing steadily. Most of it is unpublished or published in academic journals which are not usually a source used by legislators for their work. Studies in Puerto Rico demonstrate that legislators rely on other sources – not professional journals - for their projects (El Nuevo Día, 2013). Topics that were most frequently studied are strongly related to social/psychological issues of relevance on the Island including violence and crime, HIV/AIDS, mental health, and homelessness. More recent topics include psychologists’ participation in PP, environmental issues, and the participation of non-governmental organizations in public policy. Research leads naturally to describing some policy work that has been implemented on the Island. Specifically detailed are two PRPA projects, and other efforts by organizations and individuals.

Practice

Efforts of the PRPA

The first examples presented are two efforts spearheaded by the PRPA: Proposals without Colors and a Clean Electoral Campaign. Proposals without Colors was the first initiative of the CPPP. It was a coordinated effort to provide public policy proposals from psychologists and psychology students to gubernatorial candidates of the 2008 electoral campaign. The initiative was announced in a press conference. Public hearings to receive policy proposals were carried out in two regions of the Island. These proposals were analyzed and streamlined by a group of experts from various disciplines in each content area: mental health, education, and violence. The resulting document was given to the four gubernatorial candidates (CPPP, 2008). Meetings with some of the candidates or with their staff were conducted and the document was presented to the country in another press conference. Finally, the CPPP evaluated how many of their proposals were incorporated into each party’s platform. The inclusion of proposals varied across parties. As a result of this effort, the PRPA received many communications from its members and individuals from other disciplines supporting the effort and lending legitimacy to the participation of the organization in PP processes.

During the 2012 electoral process, the PRPA implemented “Campaña Electoral de Altura” (Clean or Respectful Electoral Campaign) to promote ethical standards for the political debate during the electoral process (Pérez, Rodríguez, & Serrano-García, 2014). The campaign included

Two editorials in the Island’s most important newspaper supported the campaign. Hence, for the past two elections the PRPA has remained an important voice in public debate.

Efforts from Non-Governmental Organizations

Community psychologists have also directed other major efforts on the Island focused on fostering models of participatory democracy. One is led by Cumbre Social, which facilitates people’s involvement in social problem identification, policy formulation, and implementation. The organization is currently heading participatory budgeting processes in two of Puerto Rico’s major cities. Presently, there is another national initiative called Agenda Ciudadana or Citizen’s Agenda. This organization facilitates citizen’s participation in developing policies in education, health, environment, safety and security, and economic development. During the two past electoral periods they held popular assemblies around the Island, which led to proposals for gubernatorial candidates. During the years between elections, they devoted much effort and resources to accountability of the entities that committed to furthering their proposals.

Efforts through Private Practice

Other community psychologists engage in problem definition, policy analysis, strategic planning, and program evaluation within their private consulting firms. One such firm is Énfasis. Community and social psychologists, as well as economists and planners, carry out research, organizational, and program evaluations; provide information to policy makers; perform economic analysis; develop strategic planning; and provide training. On the other hand COATTI, Inc. – which includes community, clinical and organizational psychologists in its staff – provides technical support, performs research, facilitates program development and strategic planning, provides training, and engages in program evaluation.

Governmental Programs

Community psychologists have also been active in creating and running governmental programs. The Conflict Mediation Centers of the Judicial Branch are one example. These were created in 1983 and started with just one Center in San Juan. Since then, they have flourished as a non-judicial alternative to solving civil disputes in 14 centers across the Island. A similar effort was initiated in 1976 to create the Centers for Prevention of Domestic Violence, providing services to women and their children who are victims of domestic violence as well as to offer preventive services related to the issue. These also began with one center and now have five around the Island, where various community psychologists work.

Over all, many psychologists are now active in PP processes. Community psychologists have played a leading role and many gain their livelihood in these endeavors. Most efforts are spearheaded from within non-governmental organizations, fostering bottom-up public policies. As with research, the PRPA has had a vital role in promoting and legitimizing these efforts among all specialties.

Training

If community psychologists want to increase the participation of psychologists in public policy, it is essential that students receive training related to these processes. Serrano-García and colleagues (2005) carried out a research project in 2004 to find out what, if any, preparation graduate students in psychology were receiving related to PP. This study had a qualitative component where psychology program curriculums were analyzed to identify public policy related courses and program directors were interviewed to gather their impressions about the importance of this content area. The authors identified only one graduate elective course offered at the Social-Community Psychology Program at the University of Puerto Rico. When program directors were interviewed they stated that public policy should be taught in undergraduate and graduate programs but that it would be hard to integrate them in their curriculums as it is not a priority for accreditation (Serrano-García, et al, 2005).

A follow-up of this study was carried out in 2014 (Serrano-García, 2014). Only five of 20 graduate programs currently offer courses related to PP. Some of the topics include labor relations, administration of mental health programs, and expert testimony in the courts. The UPR program still offers an elective course in which few students enroll. Program directors noted that students take courses outside of psychology, but hardly ever related to PP. Although the program directors stated in 2004 that there should be more training in PP, there has been no increase in course offerings or other experiences in the ten years between these studies.

Efforts by PRPA

As with previous areas, the PRPA has also contributed to training. Once the CPPP was created it set out to develop a model syllabus for a Psychology and Public Policy course. This syllabus could be used by undergraduate and graduate programs to develop their own or to include the course in their offerings. The syllabus was presented to program directors and has been made available through the PRPA. Recently, the syllabus was first used to teach an undergraduate level course at University of Puerto Rico, Mayagüez campus. Twenty-four students were enrolled in the course and gave excellent end-of-semester evaluations. They also presented about their experiences in a Political Science conference. A modified version of the syllabus will also be used to teach a course at the graduate level for clinical psychology students at the Ponce School of Medicine and Health Sciences.

The CPPP also offered various continuing education courses to develop specific skills psychologists need to engage in public policy. These included Media Relations and Effective Communication, How to influence Public Policy, and Stages of the Public Policy Process. Two members of the CPPP also wrote a column for the PRPA bulletin including a step-by-step guide about how to organize a press conference (Figueroa & Lugo, 2008).

Another strategy established by the CPPP was developing a practicum site for Social Community Psychology students who wanted to acquire experience in public policy. This hands-on experience allowed students to engage in various tasks including

Conclusions and Recommendations

Public policy participation, research, interventions, and training are all necessary if psychologists want to contribute to the goals of community psychology and to improve the world in which we live. These interventions should be guided by psychological expertise and values and should be supported by research from all specialties. They should not be seen as the exclusive purview of community psychologists.

In Puerto Rico, psychologists have been increasingly augmenting their participation at this level of intervention. Main forces leading to this increase have been

Unfortunately, despite these advances, training programs still lag behind in providing the education necessary for engagement in public policy processes, although a few have initiated internships and created courses. There have been, however, some developments in continuing education sponsored by the PRPA. The contributions of the CPPP have varied depending on its leadership’s time, expertise and other resources. In order for psychology PP contributions to continue its growth, these challenges need to be addressed by the PRPA.

A first recommendation is related to training. Strengthening training for work in public policy is essential. Programs should start by creating awareness at the undergraduate level of the possibilities psychologist have to influence policy making while providing examples of success stories in the area. This can be done through specific courses like the one previously mentioned, workshops and symposiums where psychologists can share with students their experiences in public policy, and recommendations. Graduate programs should include courses about policy issues and work but should also incorporate discussions of the implications of psychological research – of all specialties - for analyzing social problems and developing, implementing and evaluating policy solutions. Training programs should also identify practicum and internship sites related to public policy for their students. Finally, it would be beneficial to research attitudes and skills necessary for policy work among students and psychologists. This would facilitate creating interest in working at this level as well as developing expertise in the field.

Another recommendation focuses on the importance of disseminating the work of successful role models and programs. There is a lot of concern and fear that devoting time, or one’s career, to policy is a lost cause due to the political culture and environment (Díaz Meléndez & Serrano-García, 2012). If colleagues can see that there are many who have succeeded, and a sizeable number who make their living at this level of intervention, this could promote further engagement. This could be accomplished by conducting qualitative research to document the experiences of such individuals and organizing presentations at local conferences and university forums to dialogue with professionals and students about the experiences of psychologists in public policy. The PRPA could also include brief biographies or interviews of successful individuals or descriptions of programs in the permanent column the CPPP has in every issue of their newsletter.

Finally, the authors have demonstrated that the PRPA has had a major role in promoting involvement in public policy by psychologist. However, the voluntary nature of the Association challenges its leadership to think creatively about sustaining its CPPP. Some possible strategies may be to

The latter would narrow the Association’s interventions, but would enhance their effectiveness.

This summary should provide evidence of the impact that professional organizations can have when they include policy work and training in their agendas. If these efforts are done in conjunction with other psychological, community and government organizations, chances for success increase exponentially and thus, should be promoted.

Community psychologists are particularly prepared to spearhead efforts in public policy (SCRA, 2012). As such they should continue leading the psychological discipline in these efforts, and gain support from other specialties and disciplines. Lessons learned in Puerto Rico can serve as examples for other countries. If community psychologists are committed to social justice and change, they should continue to pave the road that has been initiated by many hard working, committed and successful colleagues.

NOTES

[1] From this point on the article will refer to social and clinical-community psychologists as community psychologists.

[2] This refers to the articles summarized in the previous section.

[3] Text in bold refers to subjects that repeat themselves in both journals.

[4] Text in bold refers to topics that appear in more than one decade.

[5] This video received an award in the Society for Community Research and Action (SCRA) Video Competition at the 2013 SCRA Biennial. It was edited by Soélix Rodríguez and Irma Serrano-García.

References

Asociación de Psicología de Puerto Rico (APPR) (2014). Políticas institucionales de la Asociación de Psicología de Puerto Rico (2004-2013). [Institutional policies of the Puerto Rico Psychology Association]. Unpublished document.

Ayala, H. (2015, February 12). De la mano la perspectiva de género con la buena salud. [Hand-in-hand gender perspective with good health]. Diálogo, Retrieved from http://dialogoupr.com/noticia/de-la-mano-la-perspectiva-de-genero-con-la-buena-salud/

Boulón-Díaz, F. (2007). La psicología como profesión en Puerto Rico: Desarrollo y nuevos retos. [Psychology as a profession in Puerto Rico: development and new challenges.] Revista Puertorriqueña de Psicología, 17, 215-240.

Committee of Psychology and Public Policy (CPPP) (2008). Propuestas sin colores. [Proposals without colors]. San Juan, PR.

Díaz Meléndez, L., & Serrano-García, I. (2012). ¿Por qué un grupo de psicólogos/as no participa en política pública? [Why a group of psychologists does not participate in public policy?] Revista Puertorriqueña de Psicología, 23 (Suplemento electrónico). http://reps.asppr.net/RePS/Vol_23_-_2012.html

Dinitto, D., M., & Dye, T. R. (1987). Social welfare: Politics and public policy. New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Dobelstein, A. (1997). Social welfare: Policy analysis. Chicago, IL: Nelson Hall.

El Nuevo Día (2013, November 10) ¿Qué leen los legisladores? [What do legislators read? ] http://www.elnuevodia.com/videos/noticias/politica/aqua©leenloslegisladores-video-152447/

Figueroa, M., & Lugo, E. (2008). Organización de una conferencia de prensa: Reto para la divulgación. [Organizing a press conference: Challege for dissemination] Boletín Asociación de Psicología de Puerto Rico, 30 (3), 13-14.

Maton, K. (2013). (Ed.) Community psychology and social policy. Global Journal of Community Psychology Practice, Special Issue, 4 (2) Retrieved at http://www.gjcpp.org/en/article.php?issue=14

Moreno-Velázquez, I., Justel-Cabrera, J., & Massanet-Rosario, B. (2007). Historia de la Psicología Industrial/Organizacional en Puerto Rico: Los primeros 35 años (1970-2005). Revista Puertorriqueña de Psicología, 17, 389-419.

N.A. (2015, March 4). Asociación de Psicología de Puerto Rico endosa proyecto de muerte digna. [Puerto Rico Psychological Association sponsors dignified death project.] Metro, p.2.

Pérez Jiménez, D., Rodríguez Medina, S. M., & Serrano-García, I. (2014). Campaña electoral de altura: Fomentando la participación ciudadana desde una organización professional. [Ethical electoral campaign: Promoting citizen participation from a professional organization]. Revista Puertorriqueña de Psicología, 25, 354-374.

Phillips, D. A. (2000). Social policy and community psychology. In J. Rappaport & E. Seidman (Eds.), Handbook of Community Psychology (pp.397-419). NY: Kluwer.

Roca de Torres, I. (2007). Algunos precursores de la psicología en Puerto Rico: Reseñas biográficas. [Some precursors of psychology in Puerto Rico: Biographical review]. Revista Puertorriqueña de Psicología, 17, 61-90.

Rodríguez, J. (2015, March 8). Mejor talento humano en las organizaciones psicológicamente saludables. [Better human talent in psychologically healthy workplaces]. El Nuevo Día, p. E-2.

SCRA (2012). Competencies for community psychology practice. http://www.scra27.org/what-we-do/practice/18-competencies-community-psychology-practice/

Serrano-García, I. (1983). Report on psychologists involvement in public policy: Puerto Rico. Unpublished document.

Serrano-García, I. (2014, September). Involving psychologists in public policy: Processes and results. Oral presentation at the International Conference of Community Psychology, Fortaleza, Brasil.

Serrano-García, I. (2013). Políticas institucionales de la Asociación de Psicología de Puerto Rico 2004-2013 [Institucional policies of the Puerto Rico Psychology Association]. Unpublished document.

Serrano-García, I, Carvallo Messa, V., & Walters Pacheco, K. (2009). Reflexiones sobre valores en psicología comunitaria: Adiestramiento ¿para qué?. [Reflections about the values of community psychology: Training for what?] In F. Cintrón Bou , E. Acosta Pérez, & L. Díaz Meléndez (Eds.), Psicología comunitaria: Trabajando con comunidades en las Américas.(pps. 227-254), San Juan, P.R.: Publicaciones Puertorriqueñas.

Serrano-García, I., Colón Rivera A., & Díaz Meléndez, L. (2005). La psicología y la política pública: Reto para el adiestramiento de profesionales en Puerto Rico. [Psychology and public policy: Challenge for the training of professionals in Puerto Rico] Revista Puertorriqueña de Psicología, 16, 219-241.

Serrano-García, I., Rosa Rodríguez, Y., & García Pérez, G. (2005) Psicología y política pública: 20 años después. [Psychology and public policy: 20 years later] Revista Puertorriqueña de Psicología, 16, 159-190.

Table 1 |

Table 2 |

Table 3 |

Irma Serrano-García and Eduardo A. Lugo-Hernández

Irma Serrano-García and Eduardo A. Lugo-Hernández

Irma Serrano-García: Irma Serrano-García is a retired Professor from the University of Puerto Rico, Río Piedras Campus. She holds a Post Doctorate in Public Policy from the Harvard University Graduate School of Education, a PhD in Social-Community Psychology from the University of Michigan. She has over 125 scholarly publications including journal articles, book chapters and thirteen books. After her retirement, Dr. Serrano-García continues to publish about community psychology, social change, participatory research, public policy, program evaluation, university teaching and learning and is a consultant to non-profit organizations and universities.

Eduardo A. Lugo-Hernández: Dr. Eduardo A. Lugo-Hernández is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Psychology of the University of Puerto Rico, Mayagüez Campus. His research focuses on promoting youth participation in school action through Community-Based Participatory Research. He is also interested in ways to promote psychologists participation in public policy.

Add Comment

![]() Download the PDF version to access the complete article.

Download the PDF version to access the complete article.

Keywords: psicología y política pública, Puerto Rico, psychology, public policy