Research on community organizations suggests there are a variety of factors related to the success of an organization’s mission. This study identifies general facilitators and challenges advocates working against human trafficking experience and the strategies utilized to overcome these barriers. Fifteen individuals who are advocates in the Chicagoland area participated in the study. Qualitative methods using the social ecological theoretical framework show personal, organizational, and system-wide factors impacting advocates. Individual support systems and advocates’ collaborations with other organizations are encouraging factors in their work. Furthermore, advocates feel motivated by trafficked persons’ stories and by the capacity to raise awareness through social media. Challenges advocates face include a lack of time and money, a lack of communication among organizations, and negative cultural attitudes related to trafficking. Results focus on the specific experiences of anti-trafficking advocates and convey strategies to provide quality services to survivors and effectively raise awareness in the general public.

Download the PDF version to access complete article, including tables and figures.

Human trafficking is a multifaceted problem involving interpersonal violence where one individual asserts power and control over another. The Trafficking Victims Protection Act (2000) defines human trafficking as the exploitation of a person for labor purposes (e.g., debt bondage, involuntary domestic servitude, or labor trafficking) or a commercial sex act (i.e., sex trafficking) through the use of force, fraud, or coercion, or when any person under the age of 18 engages in a commercial sex act (U.S. Department of State, 2010). The body of research about human trafficking primarily focused on sex trafficking and the experiences of survivors. While this research is valuable, research is limited in understanding the personal, organizational, and system-wide factors that influence how advocates and organizations work to end human trafficking. Past research suggests that combatting trafficking necessitates a victim-centered response at multiple levels that includes the perspectives of survivors, trained advocates, and collaborations among a variety of social service providers (American Psychological Association, Division 35, 2010). Little is known about the general facilitators, challenges, and strategies advocates encounter as they work against human trafficking. To address this gap in the literature, researchers interviewed 15 individuals from five organizations in the Chicagoland area working against trafficking. The study was driven by the questions: “What factors impact advocates’ work against human trafficking?” and “What strategies do advocates use to overcome challenges or capitalize on strengths?” Such knowledge may benefit organizations and communities through a greater understanding of how multiple factors may assist or hinder advocates in addressing human trafficking.

While prevalence rates may oversimplify and underestimate the numbers of this complex crime (Bales, 2012), they provide a contextual baseline for understanding the global depth of trafficking as a global social problem. It is estimated that in the U.S. 17,500 people are trafficked and 199,000 minors are sexually exploited each year (Estes & Weiner, 2001). Prevalence rates are higher for female survivors, thus human trafficking has been categorized as a form of violence against women (American Psychological Association, Division 35, 2010). Women may be more vulnerable for commercial sexual exploitation because of the impact of poverty, limited access to education, fewer employment opportunities, or an exposure to domestic violence (Ferraro & Moe, 2006). Research suggests women are significantly more likely than men to live in poverty (Chant, 2008; Pearce, 1978), be discriminated against in the division of labor (both in the home and in the workforce; Rogers, 2005), and lack access to educational or financial resources (Christopher, England, Smeeding, & Ross, 2002). There are many factors that place individuals at a greater risk to be trafficked. Many young girls from disadvantaged populations may have family duties and responsibilities that force them to drop out of school, which ultimately leaves them at greater risk for commercial sexual exploitation (Reid & Piquero, 2013). Indeed, research suggests that factors such as family structure (e.g., traditional gender roles that devalue women or discourage education) also place individuals at greater risk to be trafficked.

For both male and female youth, lower educational attainment and exposure to substance abuse in later adolescence and early adulthood are associated with a greater risk of commercial sexual exploitation (Reid & Piquero, 2013). Best-practices suggest survivors need an empowering trauma-informed model of service provision addressing these risk-factors across multiple systems (e.g., medical, judicial, counseling, and social services; Briere & Jordan, 2004). More research is needed to understand the barriers trafficked persons face in accessing services, which may be provided by advocates, but it is also critical to understand the challenges faced by advocates themselves and their organizations while providing services or raising awareness of trafficking.

Advocacy is one role that nonprofits may fill to bring together individuals who share a common concern for social justice in order to encourage social change and increase the accessibility of resources (Salamon, Hems, & Chinnock, 2000). In particular for survivors of violence, especially violence against women, advocates and those organizations trained to provide trauma-informed services are especiallycrucial because they may be better equipped to provide culturally-sensitive services and be empowering to survivors to reach personal goals (American Psychological Association, Division 35, 2010; Briere & Jordan, 2004; Sullivan & Bybee, 1999). Research on violence against women has shown that when battered women are aided by community-based advocacy interventions, survivors gain greater access to community resources, more consistent social support, and over time, experience less violence than women who do not receive advocacy services (Sullivan & Bybee, 1999). Advocates aid survivors in navigating the multiple, complex systems that survivors encounter in the process of seeking help or pursuing justice (i.e., legal, criminal, health; American Psychological Association, Division 35, 2010; Johnson, McGrath, & Miller, 2014). Thus, advocates may be particularly important in assisting survivors of trafficking through gaining access to resources, navigating multiple complex social provision systems, and by raising awareness about the issue to service providers and the general public.

Within advocacy work, there are a variety of factors that foster or inhibit the role of advocates and organizations as they assist survivors in navigating these multiple systems (American Psychological Association, Division 35, 2010). Advocates experience both facilitators and obstacles to their work against social injustices and a greater understanding of these factors may increase the effectiveness of advocates and their work. The present study seeks to describe the factors impacting the work of human trafficking advocates in order to better understand what helps and challenges them from an ecological perspective (i.e., individual, organizational, and system-wide levels).

Despite the importance of advocacy work, little is known about what helps or hinders an advocate’s ability to access resources for survivors. Research with healthcare advocates for sexual assault survivors note that advocacy organizations face funding shortages and difficulty collaborating or communicating with other service providers inside or outside of their organization (Johnson, et al., 2014; Payne, 2007). Transportation and geographic characteristics of a region may hinder an advocate in accessing services for a survivor; however, some geographic characteristics may also help advocates, such as living in a smaller community, which can create a stronger network among service providers and may make services more accessible and attainable (Johnson, et al., 2014). Provided that little is known about what aids or impedes the effectiveness of advocates in organizations working against human trafficking, a deeper understanding of these factors may help organizations to better train and equip their advocates to assist survivors and raise awareness within their community context.

Present Study

The present study utilizes a social ecological perspective (i.e., individual, organizational, and system-wide levels) to describe what helps and hinders advocates in their work to end human trafficking within the context of Chicago, IL. While the research on human trafficking in Chicago is limited, the Chicagoland area is a hub for human trafficking, likely because of its proximity to multiple airports and high violence and gang activity (often involved in sex trafficking; Goh, 2014). Raphael and Shapiro (2004) suggest that many girls and women who engage in sex work in Chicago are or have been trafficked and were first purchased for sex when they were under the age of 18 or were sold by a family member. Research to understand the effectiveness of advocates working to end human trafficking is limited, specifically with respect to the personal, organizational, and system-wide factors that influence their advocacy work. Thus, the present study is motivated by the following research questions: “What factors impact advocates’ work against human trafficking?” and “What strategies do advocates use to overcome challenges or capitalize on strengths?” The present study seeks to add a greater understanding of how multiple factors may assist or hinder advocates in addressing human trafficking survivors and incorporates perspectives from advocates working to end multiple forms of trafficking (e.g., sex and labor trafficking).

Method

Design

The present study utilizes qualitative description from a social ecological approach. Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) social ecological model of human development focuses on person-context interactions, which encourages the examination of multiple perspectives to assess how different systems interact with one another. A social ecological perspective is especially useful for community issues, like human trafficking, because many individuals, groups, and systems are involved. Personal level factors directly relate to the individual, such as family, peers, and personal characteristics or attributes. Organizational level factors relate to the larger system such as the advocacy organization or other organizations with which the advocate collaborates. System-wide factors are at the largest level and are related to community structure, attitudes, and legislation. Advocates experience challenges or assistance at all three of these levels (i.e., personal, organizational, system-wide).

Sample

The study sample is comprised of 15 individuals who are volunteers or paid employees at five anti-human trafficking community-based organizations in the Chicagoland area (i.e., urban and surrounding suburban areas of Chicago). Individuals represent a variety of roles within these organizations: three are executive directors, six are specialized directors (e.g., communications director, program director, volunteer director), three are interns, and three are volunteers serving on councils or coordinated teams. Participants shared experiences from organizations that they are currently or were previously involved with, focusing on a variety of tasks such as awareness raising, direct service, intervention, legal assistance, and policy advocacy. Some participants work with organizations serving one population (i.e., adolescent girls or men in sex work) while other organizations serve any individual over the age of 18 who has been trafficked. Our sample also includes organizations focused on raising awareness in the Chicagoland area. Participants have been involved in advocacy work against human trafficking for durations ranging from one to eight years. Eleven of the 15 participants are women. The age of the participants ranges from 25 to 62 (M=32.4 years old); 12 participants self-identified as “White,” two identified as “Asian American/Asian,” and one identified as “Jewish.”

Data Collection and Procedures

The university’s Institutional Review Board approved the study. Potential participants and organizations were identified through personal contacts and Internet searches. The researchers emailed a recruitment script that detailed the purpose of the study to executive directors and personal contacts. Individuals who wished to participate emailed the first author to schedule an individual audio-recorded interview at a mutually agreed upon time and location. Before officially beginning the interview, the premise of the research project was discussed and written informed consent was obtained. Individual interviews were then conducted using a semi-structured interview guide that was divided into four parts: 1) demographics and organizational roles, 2) facilitators that influence participants’ abilities to advocate or raise awareness for survivors of human trafficking, 3) barriers to anti-trafficking work, and 4) strategies to overcome these barriers. Each participant was interviewed once and after each interview, the first author created “memos” in order to record her initial thoughts and observations (Burnard, 1991). Audio-recorded interviews ranged in length from approximately 30 to 90 minutes. All interviews were audio recorded and then transcribed verbatim. The first author reviewed the transcripts for content and accuracy of transcription.

Data Analysis

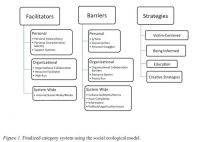

Data was analyzed using content analysis (Burnard, 1991), according to the social ecological model (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). The first author began by making notes after interviews with initial observations and continued to memo during the initial analysis process to note categories and emerging themes. Transcripts were read by the first author and notes were made in the margins. All transcripts were reviewed again by the first and second authors and open coded, noting as many categories as necessary to capture the content of the interview. The first and second authors assessed the categories and independently created a category system that grouped together categories into higher order headings following the social ecological model. The goal of this stage in the analysis was to create a category system that collapsed headings into subheadings. The first and second authors then came together with their independent category systems and worked to combine their structures to capture the content of the interviews while also reducing repetitive headings. A combined category system was developed and the experiences of advocates were captured under the headings of facilitators, barriers, and strategies with specific personal, organizational, and system-wide subheadings. This combined structure was brought to the third author who checked for content, clarity, and consistency. After the combined category system was finalized (See Figure 1), the transcripts and thematic structure were uploaded into the online qualitative data analysis software Dedoose and each transcript was coded within this program. Researchers then analyzed the codes by category to write the results.

Findings

Findings will be presented according to the social ecological model - individual/personal, organizational, and system-wide facilitators of advocacy work will be presented followed by individual/personal, organizational, and system-wide barriers to advocacy work. The findings section will conclude with suggested strategies that may enhance personal, organizational, and system-wide approaches to anti-human trafficking advocacy work.

Facilitators

Personal. Advocates note the importance of strong support systems, especially when confronting barriers. These supports consist of others within the organization who were like-minded or who share their knowledge of human trafficking. These individuals offer understanding and advice around how to deal with barriers the advocate encounters. Family members, friends, or significant others also offer support with words of encouragement, resources and information, or networking.

Various personal characteristics or parts of advocates’ identities are also facilitators such as a personal curiosity, passion for the issue, ability to take initiative, or their heritage and family identity. For instance, one advocate shares that her Jewish identity drives her passion for social justice work:

Being Jewish...because we have a strong line of social activism, specifically Jewish women. And I think that is because of just years of abuse by everybody. And like, ok, are we going to allow ourselves to be victims or are we going to be survivors? So I think that has been instilled with me as well. So, I think, as part of my identity, those are the things that drive me.

Other advocates note faith in God as a personal motivator that gives them hope, a mission, and perseverance, especially when facing roadblocks or an unknown future. These personal characteristics and aspects of advocates’ identities provide them with a sense of purpose.

Participants often recount either “aha” moments (e.g., first becoming aware of trafficking) or personal experiences (e.g., personal abuse history) that motivate them to address the issue of human trafficking and a cycle of violence. As one participant states,

I was sexually abused from age 4 to 10 and I dealt with that in an unhealthy way throughout high school and then I was introduced to women’s studies and my life was changed. And I have done a lot of activism work since then…And so, my personal story, not that it drives everything I do, but it is a big part of who I am, and the way that I view things. So I think that is underneath all of it -- a huge motivator because the person who abused me was abused as well and I know the cycle of violence. And if I am going to make the conscious choice to not participate in that abuse, I want to help others figure out that they can do that too. Or at least provide them the space so that they don’t feel like they have no way of gaining power…So that then they don’t perpetuate that system by trying to gain power in an unhealthy way. So that is the underlying motivator for me.

For this participant, her own experience of abuse compels her to become an advocate, create a space for others to process their experiences, and to empower others to end the cycle of abuse.

Organizational. At the organizational level, advocates identify a variety of resources that help their work such as well-trained colleagues, a clinical/trauma-based approach, a solid volunteer base, grant money or donors, and donations of resources (i.e., space, food, clothing). The presence of these resources has improved the capacity of the organization and the services provided to survivors. Advocates also identify access to and participation in trainings as key facilitators and share the importance of these trauma-based trainings for individuals assisting trafficking survivors:

We hire, train, train, train, and we use survivors to help us train...we have [Name of Community Partner] on contract with our home and she comes over, not only meeting with the girls but she meets with the staff. And it’s a real benefit to us because of her approach [referring to her survivor-focused approach], but training is everything to your staff.

Further organizational characteristics that were helpful to advocates are those organizations that are “well-run,” hold consistent meetings, foster camaraderie within the organization, connect to the community needs, and carry out successful events. One participant notes that the reputation of their organization is helpful in a variety of ways:

And this is another thing, you talk about what helps me, the [Name of Organization], and their name, and their rep...We’ve been around...and as a result of that the organization, the persona of the organization, our brand identity, our recognition, our trust, people have in us is a gigantic asset.

Indeed, a good reputation assists advocates and organizations in collaborating with others. Local businesses, other agencies working in violence prevention/intervention, churches, and national policy organizations are collaborators who aid advocates and their organizations. These collaborations empower and energize advocates as they facilitate connections, share information, increase resources, and build a supportive network. One participant shares how their partner organization is: “really being a cheerleader for us and connecting us...I would have never known who to talk to, in a lot of things.” Interestingly, advocates even identify groups not directly involved, such as feminist groups and artist networks, as facilitators of their work.

System-wide. The Internet provides information and networks for advocates to connect with other organizations nationally and internationally, specifically to connect and learn from other human trafficking organizations. Organizations like The Polaris Project and The Not for Sale Campaign have online resources that increase advocates’ personal knowledge about trafficking and give them ideas for awareness-raising strategies that their organizations could implement. One major resource that assists advocates, organizations, and the general public is the Human Trafficking Hotline facilitated by The Polaris Project: “The human trafficking hotline is…also a place where you can call and ask for resources…it’s not just a place to report…and hang up.” Social media sites, such as Facebook and Twitter, are another networking and relationship-building resource. Advocates note there is a lot of misinformation in the media about trafficking and advocates use Facebook and Twitter accounts to correct misinformation and to raise awareness through posting and sharing relevant news articles. One advocate notes how she replies to posts with stereotypes about human trafficking on Facebook and Twitter through attaching articles and links to blogs to counteract the stereotype and raise awareness. Advocates also raise awareness of trafficking through the Internet by creating social media accounts, smartphone applications, and responding to media coverage that sparks further conversations.

Barriers

Personal. Participants identify a lack of resources, such as time and money, as personal barriers to their advocacy work. Individuals who are unpaid volunteers have to balance their volunteer work with their paid jobs. The following participant’s experience captures this well:

I think the challenge is always to figure out ways to be more fully engaged…in different capacities...In the current station of life that I am in right now, I am not able to give my…full work towards really advocating or doing...a lot of significant work. It’s sort of like the scraps in my spare time that I am able to dedicate to it. And I think that’s the way it is for a lot of people...That they don’t necessarily have the time, you know, or finances, to really afford...to dedicate a lot of time to it. I think that’s the hard thing.

Participants express a desire to be involved in the work, however are limited by time and financial restraints.

Some advocates are worn down from organizational politics or from the scope of need for trafficking survivors. Others share personal struggles such as feeling burnt out, too young, or inadequate. One participant states: “But, even still...I feel personally insecure...am I trying enough or do I have enough skills and experience to...try to promote things that are actually working, or am I just going to kind of do what I can.” Advocates struggle with feeling ill-equipped to carry out their work for a variety of reasons such as being discouraged by the magnitude of the issue, or lacking the resources, patience, or emotional energy advocates need to continue their work when facing barriers.

Additionally, many advocates do not having direct contact with survivors, but instead work in fundraising, events planning, administrative work, or community education. Advocates understand that due to the effects of the psychological and physical trauma experienced by survivors and threats of retaliation from traffickers, many organizations seek to protect survivors’ identities and privacy by limiting direct access. Advocates who have limited access to survivors and survivor’s input feel a tension because advocates do not know how organizational decisions are viewed by survivors and feel a general disconnection from the individuals they are assisting. Advocates, specifically those without direct contact with survivors, struggle to stay emotionally connected to the cause while immersed in the administrative details of running a program, planning an event, or fundraising.

Organizational. Participants do not have enough organizational resources and note the need for more funding. They describe how difficult it is to obtain grants that then restrict their ability to fully serve trafficking survivors due to red tape or restrictions on who can be assisted. Other organizations that did not have an established office location struggle finding spaces for their teams to meet on a regular basis or host events to raise awareness. Logistically, organizations that rely on unpaid volunteers have difficulty coordinating the volunteers’ variable work schedules. Furthermore, advocates experience difficulty maintaining a consistent base of volunteers, specifically in a transient urban city like Chicago.

Some advocates are frustrated with “poorly run” organizations or leaders who lack organizational skills. When information about their work, partnerships, or events are vague or when leaders fail to translate information into specific tasks, advocates feel the leadership lacks organization. Advocates note how a lack of planning and research by organizations results in events being unsuccessful, actions that are insensitive to survivors, or volunteers feeling like their time is being wasted. One individual states, “We don’t meet regularly...I find when we do get together, there’s a lot of time wasted.” This advocate does not believe that the organization adequately utilizes staff and volunteer time and this may be a contributing factor to the organization’s inability to maintain a consistent volunteer base. Indeed, advocates share how the organization’s poor management decreases volunteer involvement as leaders fail to respond to volunteer inquiries in a timely manner and fail to keep in regular contact with their volunteers. Participants are less committed to organizations that they believe to be “poorly run.” They feel a tension between commitment to the cause and frustration of working with organizations.

Another organizational level challenge is collaboration with other community-based organizations, which is demonstrated in a lack of communication from partner organizations, feeling of isolation from others, and restrictive bureaucratic structures within and between organizations. For example, one advocate expresses frustration with a lack of communication between her organization and the partner organization when planning an event when she states:

Like we’re partnering with them...we’re providing volunteers, and I don’t know anything about it, how can I...help them...be successful?…But I don’t know anything [about the event]...and we’re partnering with them, you know?

Advocates also cite challenges such as gaining entry into other organizations for education or fundraising purposes, specifically schools, community centers, and religious organizations.

System-wide societal and cultural challenges. Advocates who are working to end trafficking encounter beliefs and attitudes about the problem of trafficking, which impact the support and capacity of advocates to carry out their work. Participants cite challenges of social norms of masculinity, an over-sexualized culture, myths about trafficking, and victim-blaming attitudes toward survivors. Advocates reference popular movies (i.e., “Taken,” “Pretty Woman”), television shows (i.e., “Toddlers and Tiaras,” “Pimp my Ride”), music styles (i.e., hip hop and rap), and subcultures (i.e., pimp culture, the American culture) as barriers to their work. These images perpetuate stereotypes and misinformation, desensitize youth, over-sexualize/objectify individuals, and normalize violence. The phrase “sex sells” is repeated in multiple interviews by advocates noting how culture sexualizes women and glamorizes sex work.

The negative impact of traditional gender norms is another theme and advocates note how these norms restrict men from talking about being raped or being trafficked. One participant who serves male trafficking survivors notes that men feel ashamed of being trafficked or raped because they think they should have been able to protect themselves: “Because it’s like ‘what kind of man am I that this happened to me and I wasn’t able to protect myself or got myself into this situation?’” Advocates note how young girls from disadvantaged populations may have family duties and expectations that force them to drop out of school and put them at a greater risk to be trafficked. These girls often have less economic opportunity due to leaving school, which can make them a target of traffickers working in their low-income neighborhoods: “Low socioeconomic status in girls and how they’re dropout rates are insane...because they have to take care of their family. Meaning their brothers and sisters…so their education is always in jeopardy because of various gender roles.” Advocates link norms about gender with difficulties for survivors and barriers to collaborating with others in their advocacy work.

Advocates also face a challenge with individuals in their communities who are reluctant to recognize trafficking in the US or in Chicago specifically.

There a lot of people who don’t think it happens here or just you know they think of brothels in Cambodia and they think of sweatshops in China and India and Bangladesh and that’s about it. Or you know prostitution in Eastern Europe or Russia and that’s probably the scope of what they envision...in the media it has been painted as international.

Advocates encounter individuals who deny the existence of trafficking within the U.S. and they struggle to raise awareness and gain community support for survivor resources because of this attitude that trafficking “doesn’t happen here.” Cultural attitudes toward survivors and other related topics, like sex work, rape, and gender norms make community members reticent to discuss and address trafficking in their communities. Advocates note that because human trafficking is a complex issue, many people have difficulty understanding the role of coercion, control, and the effect of systemic abuse within trafficking. One advocate identifies this issue complexity as her largest barrier:

I think the biggest barrier is having people understand that people do not enter on their own freewill...they are…persuaded and tricked and forced emotionally and physically...I think that a lot of times people don’t understand…“Well, she’s the prostitute. She made herself…she decided to have sex for money…But no, you’re not looking at the fact that she was abused from age six, sexually by her uncle or whatever, and now she’s 14 and she has no other way of how to express herself but through sex and you know…it is a horrible cycle. So I think that is the biggest barrier for people to understand...I think even my own family members and friends, they don’t quite understand that, you know, to them it is a choice. But, what choice do you have when you are 12 years old? I think [this] is the biggest barrier.

This tension is not just present in others, but advocates also note experiencing an internal tension over understanding the complexity of trafficking when assisting survivors who return to their trafficker or survivors who do not personally identify as a trafficking survivor. Advocates state a lack of understanding about the complexity of trafficking as a challenge both to their efforts to advocate for survivors and to educate others about trafficking.

Additionally, a lack of information or misinformation is an obstacle for advocates. One source of misinformation is media images that perpetuate stereotypes or over-simplify the issue (i.e., focus on the rescue with no mention of the after-care services or process). Media misinformation is a challenge because “what the media...shows and what movies show and...what other outlets show, isn’t wrong, it’s just never the whole picture.” Across organizations and roles, advocates express a need for more credible research about trafficking and their advocacy work.

Other challenges include issues with the U.S. justice system, legislation, and politics. Advocates working against sex trafficking are particularly frustrated with the lack of significant repercussions “for Johns” and pimps. Legislation loopholes and lack of sensitivity to trafficking are significant barriers to advocate’s work:

And I mean I think when we look at our laws, that’s another barrier because while we may recognize a trafficking situation if the state you’re in...if their law is written in a certain way where the language allows loopholes to allow a trafficker to...get out of the situation free then that’s going to affect how efficiently and how adequately we’re able to address trafficking in a state or in our community.

Participants talk about how gangs increase the risks of being trafficked and involve a sophisticated system that is often necessary for an organized crime like human trafficking. They describe how gang involvement in human trafficking is common in Chicago, which may be because of the potential profit of human trafficking as a person can be sold multiple times while drugs are only sold once. Trafficking is deeper than any one system, and advocates struggle to unpack the tangled roots of social class, racism, discrimination and neighborhood violence that interact to increase the vulnerability of certain populations.

Strategies

Victim-Centered. Advocates emphasize the need to be connected to survivor voice and victim needs. Participants stress the use of empowerment and trauma-informed models of intervention. One strategy to empower survivors is asking for the input of survivors when forming and evaluating programs and campaigns. Advocates state that survivor voice is key to the movement to end trafficking and that in their own work, seeking to understand trafficking from the words and stories of those who have lived the experience is essential:

I think…the thing that I’ve found most effective is to always be…learning from women who’ve been in the life...or [who] have been trafficking victims, I think I…consider myself to be a very privileged lifestyle and there is no possible way that I can understand the complexities of being a trafficking victim.

Advocates benefit greatly from trainings conducted by survivors who encourage advocates to not force opinions or beliefs on survivors but to simply extend the offer of help. By staying victim-centered, advocates express that they counteract the control and abuse that many survivors have experienced, while also growing in their own knowledge and awareness.

Education. Another strategy to overcome some of these challenges is education. Advocates identify how, both personally and in their communities, education helps improve sensitivity to survivors. Education helps unpack the complexity of trafficking to those who may oversimplify the issue. A key aspect of prevention is to teach children about coercion, specifically giving them a voice to share the challenges in their lives and neighborhoods by discussing instances of community violence or pressures to be involved in gangs. This may help identify children who are at-risk or may mitigate the impact of the violence through providing a safe space for conversation and dialogue.

Advocates also emphasize the importance of education in areas related to human trafficking like domestic violence, child abuse, and sexual assault. People’s attitudes towards these forms of violence may shape their response to survivors of human trafficking. One advocate shares that when she has heard harmful attitudes or myths her previous response would be anger; however, her strategy has changed: “I realized that the better thing for me to do is to provide education if they wanted it…invite them to come to events in the community that were being offered...places for them to learn more at their level of comfort.”

Creative Strategies. Advocates identify a variety of creative ways to overcome barriers. One advocate talks about the work of his organization to educate business owners in low-income neighborhoods about various signs of trafficking. These business owners are asked to track patterns that they observe of traffickers and then report their observations to law enforcement. This organization uses the “eyes and the ears of the concerned,” committed citizens in order to gain information to assist victims and prosecute traffickers. Another advocate has designed a program to empower young girls through a yoga program focused on a positive self-image. Other advocates discuss awareness-raising events like flash mobs and stage performances and fundraisers such as annual bike rides.

Being Informed. When discussing strategies to overcome barriers, advocates emphasize the importance of connecting with organizations that are already working in the community:

There are certain organizations in the city that are so well established that you don’t move forward until you contact them and get their support, and even on [Specific Program of an Organization] like we wouldn’t be moving forward if I didn’t have the blessing of so many of our collaborators.

Not only is gaining the support of other organizations important, but so is doing one’s research and recognizing one’s own perspective or biases before acting. With larger systemic issues at play when advocating for survivors, it is crucial to be informed about the past and present climate of the community towards survivors and the organizations that seek to support them.

Discussion

This study identifies personal, organizational, and system-wide facilitators, barriers, and strategies for advocates who are working to end human trafficking in the Chicagoland area. Across multiple levels, the data find that advocacy work is facilitated by personal support systems and collaborations with other organizations and the most prevalent barriers advocates experience are cultural attitudes and a lack of organizational resources. Specific experiences of anti-trafficking advocates using a social ecological model convey various strategies to overcome barriers and to continue to work against human trafficking, such as educating the general public and being victim-centered

Human trafficking advocates face a variety of personal factors that both help and challenge their work. Findings from this study are consistent with Killian’s (2008) findings that individuals who assist survivors of trauma need support systems, both personal and professional, and that spirituality is important for self-care and the continuation of their work. These findings about burnout, poor system responses, and collaboration issues with other organizations echoes research by Killian (2008) and past research that has also found that advocates and helping professionals experience personal barriers, such as burnout, and organizational and systems barriers surrounding collaboration (Payne, 2007). Similarly, like the advocates in this sample, nurses who advocate for their patients note frustration with system responses and they experience personal barriers such as lack of time and a need for greater training and education to better assist their patients (Hanks, 2007). Individuals working to end human trafficking experience similar barriers and facilitators to helping professionals and advocates working with survivors of violence against women.

Consistent with past research on advocate experiences, non-profit and advocacy agencies often have a lack of resources and difficulty defining a clear mission for the organization (Donaldson, 2007; Trickett, 1996). Funding and staff size are also two key factors that influence both the organization’s and the advocate’s effectiveness in responding to the needs of the community (Donaldson, 2007). Not surprisingly, advocates in the present study note that having well-trained staff is a facilitator to their work, while a lack of volunteers or funding is a challenge to their work. However, organizational collaboration is a key facilitator as collaborations across organizations that may join resources and advocates to create a community response to social issues (Marullo & Edwards, 2000; Roussos & Fawcett, 2000). Future research with human trafficking advocates may assess the potential of a coordinated community response to human trafficking, much like those that have been done with other forms of violence against women (i.e., domestic violence; Bouffard & Mufti?, 2007).

Community, cultural, and system-wide factors are also identified by anti-trafficking advocates in the present study. Cultural myths, attitudes, and norms serve as challenges to social issues like human trafficking, and other research notes the impact of cultural attitudes, media, and current events on advocacy organizations (Donaldson, 2007). Research on public perceptions of human trafficking may be particularly relevant as the public decides whether or not to support the programs of human trafficking organizations. A lack of awareness may be related to students and professionals not taking part in public policy advocacy efforts within the field of psychology (Heinowitz et al., 2012). Much of the research on public opinion demonstrates that individuals recognize the severity of human trafficking and experience empathy towards survivors (Houston, Todd, & Wilson, in press), but often struggle to understand the complexity or fail to reflect on the larger social inequalities that create vulnerabilities to being trafficked and may perpetuate the cycle of abuse (Buckley, 2009; Farmer, 2010; Herzog, 2008; Pajnik, 2010). The majority of these studies have been conducted internationally and future research should assess the public opinions and attitudes towards human trafficking in the U.S.

Limitations and Implications

The present study describes the experiences of 15 anti-trafficking advocates in the Chicagoland area, and is not without limitations. First, the sample is predominantly white women and further studies should seek to incorporate greater racial and gender diversity. Furthermore, the present study consists of advocates from five organizations working against human trafficking. A sample with a wider variety of organizations (e.g., those working against human trafficking and others who address violence against women) needs to be included in future research. Future research may also look to expand the present study to a larger number of organizations or to advocates who are also survivors, especially given that the present study notes the importance of survivor voice in advocacy efforts. Lastly, this study focuses solely on the Chicagoland area. Some of the factors that influenced advocates in Chicago may be universally experienced in advocacy organizations; however, they may be unique factors that are influenced by geographic region such as the nature of human trafficking in a large urban area (i.e., advocates noted the prevalence of gang involvement). Further research should explore if different geographic locations, such as more rural areas, experience similar (or different) barriers and facilitators.

The present study has implications for advocates and organizations. For advocates, our findings point to the importance of intentionally cultivating passion and attending trainings that continue their education. Advocates identify that continued education and staying close to the voices of survivors fueled their passion for advocacy. Connecting to support systems and others working for the cause, balancing responsibilities, and connecting to their passion may be crucial self-care techniques that advocates should be mindful to employ. These may be particularly important for the longevity and impact of their individual and organizational advocacy. For organizations, these implications for advocates are also extremely important as longevity and impact are key concerns and they may benefit from cultivating the passion of their advocates to encourage sustainable and quality services. Organizations may connect others working for the cause through collaborating with other organizations, which, as this study suggests, may be integral to their success as well. It may be beneficial for organizations to collaborate with diverse social issues that are related to human trafficking such as intimate partner violence and sexual assault in order to share resources, trainings and strategies for raising awareness about violence against women. Future research would benefit from examining the impact of these collaborations and the elements that make them particularly successful. Furthermore, research into the self-care strategies of advocates and how organizations may encourage or cultivate these strategies is crucial as the longevity and quality of advocacy and services is at stake when burnout is a higher risk.

Community psychologists are well-situated to assist advocates and organizations in the work to end human trafficking. Organizations may benefit greatly from research and evaluation on their programs for survivors with a particular emphasis on the role of survivor-voice. Survivor-voice is a key emphasis that advocates place on both their individual passion and the organization’s impact, thus community psychologists and their value of empowerment may be crucial to advocate for and implement survivor-empowering strategies. Furthermore, with training in participatory action research, community psychologists may be key partners to work against trafficking in order to facilitate empowering methods that incorporate multiple stakeholder voices across multiple levels to raise awareness and implement change. Community psychologists should extend the present study to examine the cultural attitudes and myths that negatively impact survivors, advocates, and organizations in order to inform sensitivity trainings and community education that educate service providers and the broader community. Community psychologists may also utilize the present study and future research on human trafficking to advocate for empowering and sustainable public policy efforts. Through research, evaluation, interventions, and public policy, community psychologists have a key skillset that can be applied to address the needs of survivors and those who seek to assist them (i.e., advocates and organizations).

Conclusions

This study contributes to the knowledge about community-based advocacy work to end human trafficking by informing advocates, community members, and organizations about the facilitators, barriers, and strategies suggested by those working in the field. The results of this study suggest that facilitators and barriers are experienced at multiple levels by advocates working to end human trafficking. By analyzing these factors from the social ecological model, the authors hope to encourage individuals and organizations to address factors at multiple levels. This study offers strategies to overcome barriers that advocates experience when working to end violence. The present study hopes to extend current research on advocacy work against interpersonal violence and to facilitate further research into the effectiveness of advocates’ work to reduce the effects of trafficking.

References

American Psychological Association, Division 35: Special Committee on Violence Against Women. (2010). Report on Trafficking of Women and Girls. Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/pi/women/programs/trafficking/report.pdf

Bales, K. (2012). Disposable people: New slavery in the global economy. University of California Press.

Bouffard, J. A., & Mufti?, L. R. (2007). An examination of the outcomes of various components of a coordinated community response to domestic violence by male offenders. Journal of Family Violence, 22, 353-366. doi: 10.1007/s10896-007-9086-y

Briere, J., & Jordan, C. E. (2004). Violence against women: Outcome complexity and implications for assessment and treatment. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 19, 1252-1276. doi: 10.1177/0886260504269682

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Buckley, M. (2009). Public opinion in Russia on the politics of human trafficking. Europe-Asia Studies, 61, 213-248. doi: 10.1080/09668130802630847

Burnard, P. (1991). A method of analyzing interview transcripts in qualitative research. Nurse Education Today, 11, 461-466. doi:10.1016/0260-6917(91)90009-Y

Chant, S. (2008). Feminization of Poverty. The Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Globalization.

Christopher, K., England, P., Smeeding, T. M., & Ross, K. (2002). The gender gap in poverty in modern nations: Single motherhood, the market, and the state. Sociological Perspectives 45, 219–242.

Donaldson, L. P. (2007). Advocacy by nonprofit human service agencies: Organizational factors as correlates to advocacy behavior. Journal of Community Practice, 15, 139-158. doi:10.1300/J125v15n03_08

Estes, R., & Weiner, N. (2001). The commercial sexual exploitation of children in the U.S., Canada, and Mexico. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania.

Goh, A. (2014). Chicago: A national hub for human trafficking. Juvenile Justice Information Institute. Retrieved from http://jjie.org/chicago-a-national-hub-for-human-trafficking/

Hanks, R. G. (2007). Barriers to Nursing Advocacy: A Concept Analysis. Nursing Forum, 42(4), 171-177. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6198.2007.00084.x

Heinowitz, A. E., Brown, K. R., Langsam, L. C., Arcidiacono, S. J., Baker, P. L., Badaan, N. H., & ... Cash, R. (2012). Identifying perceived personal barriers to public policy advocacy within psychology. Professional Psychology: Research And Practice, 43(4), 372-378. doi:10.1037/a0029161

Herzog, S. (2008). The lenient social and legal response to trafficking in women: An empirical analysis of public perceptions in Israel. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 24, 314-333. doi: 10.1177/1043986208318228

Houston, J. D., Todd, N. R., & Wilson, M. (in press). Preliminary validation of the Sex Trafficking Attitudes Scale. Violence Against Women.

Farmer, M. (2010). Human trafficking, prostitution, and public opinion in Hungary: Interviews with Hungarian university students (Master’s Thesis). Retrieved from CEU ETD: www.etd.ceu.hu/2010/farmer_margaret-clair.pdf

Ferraro, K. J., & Moe, A. M. (2006). The impact of mothering on criminal offending. In L. F. Alarid & P. Cromwell (Eds.), In her own words: Women offenders’ views on crime and victimization (pp. 79-92). Los Angeles, CA: Roxbury Publishing.

Johnson, M., McGrath, S. A., & Miller, M. H. (2014). Effective advocacy in rural domains: Applying an ecological model to understanding advocates’ relationships. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, doi: 10.1177/0886260513516862

Killian, K. D. (2008). Helping till it hurts? A multimethod study of compassion fatigue, burnout, and self-care in clinicians working with trauma survivors. Traumatology, 14, 32-44. doi: 10.1177/1534765608319083

Marullo, S., & Edwards, B. (2000). From charity to justice: The potential of university-community collaboration for social change. American Behavioral Scientist, 43, 895-912.

Pajnik, M. (2010). Media framing of trafficking. International Feminist Journal of Politics, 12, 45-64. doi:10.1080/14616740903429114

Payne, B. K. (2007). Victim advocates' perceptions of the role of health care workers in sexual assault cases. Criminal Justice Policy Review, 18, 81-94. doi: 10.1177/0887403406294900

Pearce, D. (1978). The feminization of poverty: Women, work, and welfare. Urban and Social Science Review, 11, 28-36.

Raphael, J., & Shapiro, D. L. (2004). Violence in indoor and outdoor prostitution venues. Violence Against Women, 10, 126-139. doi: 10.1177/1077801203260529

Reid, J. A., & Piquero, A. R. (2013, December 22). Age-graded risks for commercial sexual exploitation of male and female youth. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. Advance Online Publication. doi: 10.1177/0886260513511535

Rogers, B. (2005). The domestication of women: Discrimination in developing societies. Routledge.

Roussos, S. T., & Fawcett, S. B. (2000). A review of collaborative partnerships as a strategy for improving community health. Annual Review of Public Health, 21, 369-402.

Salamon, L. M., Hems, L. C., & Chinnock, K. (2000). The nonprofit sector: for what and for whom? (Working Paper No. 37). Retrieved from The Johns Hopkins Center for Civil Society Studies website: http://ccss.jhu.edu/.

Sullivan, C. M., & Bybee, D. I. (1999). Reducing violence using community-based advocacy for women with abusive partners. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 67, 43-53. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.67.1.43

Trickett, E. J. (1996). A future for community psychology: The contexts of diversity and the diversity of contexts. American Journal of Community Psychology, 24, 209-234.

U.S. Department of State. (2010). What is Modern Slavery? Retrieved from

Figure 1: Finalized Category System Using the Social Ecological Model |

Jaclyn D. Houston, Charlynn Odahl-Ruan, Mona Shattell

Jaclyn D. Houston, Charlynn Odahl-Ruan, Mona Shattell

Jaclyn D. Houston, MA is a graduate student of community psychology at DePaul University in Chicago. Her research focuses on attitudes toward violence against women. Specifically, she examines how individuals (e.g., rape victim advocates and the general public) and groups (e.g., religious congregations) understand and respond to survivors' experiences of violence. Email: jaclyn.kolnik@illinois.gov. Corresponding address: 300 West Adams Street Suite 200 Chicago, Illinois 60606.

Charlynn Odahl-Ruan, MA is a Clinical-Community Psychology doctoral student at DePaul University in Chicago; she received a Master of Arts degree in Clinical Psychology from DePaul and a Master of Arts in Counseling Psychology from New York University. Her research focuses on the empowerment and well-being of women, including the impact of gender role ideology, the effect of spirituality and gender norms upon women's identity formation, and gender-based economic disparities. She also studies the impact of self-care strategies on vicarious trauma of advocates and therapists working with trauma survivors.

Mona Shattell, PhD, RN, FAAN is associate dean for research and faculty development in the College of Science and Health, and professor in the School of Nursing at DePaul University in Chicago. She received a PhD in nursing from the University of Tennessee Knoxville, a Master of Science degree in nursing from Syracuse University, and a Bachelor of Science degree in nursing, also from Syracuse University. Dr. Shattell is Associate Editor of Advances in Nursing Science and Issues in Mental Health Nursing, a regular blogger for The Huffington Post, and the author of more than 100 journal articles and book chapters.

Add Comment

Articles from Around the Globe

SCRA Mini-Grants Spotlight: WRITE ON

SCRA Mini-Grant Spotlight: Beyond Expectations

THEory into ACTion: A Bulletin of New Developments in Community Psychology Practice

Share This

![]() Download the PDF version to access the complete article.

Download the PDF version to access the complete article.

Keywords: human trafficking; advocacy, social ecological model, community-based organizations, qualitative research